Society is increasingly becoming multicultural, with more pressure to improve the quality of intercultural interactions. Higher education institutions are experiencing internationalization through increased mobility of students and faculty, which creates the need to manage diversity with the imperative of smoothing communication, reducing stress and making studying and working in a multicultural environment more efficient. Employers also dictate a need to educate culturally competent professionals, who are capable of succeeding in a globalized environment characterized by increased workforce mobility and international assignments. Intercultural competences discourse has a long track with researchers and practitioners, without any agreement on its definition or measurement, but with a clear message that cultural diversity will not result in increased intercultural competences. In this paper, intercultural competences are viewed as a transversal learning outcome, considering the increasing internationalization of higher education institutions. The research is qualitative in nature, based on the analysis of course evaluations and an open-ended survey. This study used a purposeful sample of current and former students who have been exposed to a diverse intercultural environment while studying at an international business school in Sweden. Based on the findings, a course design is suggested where exposure to cultural diversity is guided and facilitated by bringing students to collaborate in an assignment-driven context, with a culturally diverse group composition. Lecture-based components of the course are balanced with the addition of a component of self-reflection assignment, providing both culturally specific and general knowledge, thus contributing to the ability to extrapolate the experience on future intercultural encounters.

1 Introduction

Globalization has propelled the internationalization of higher education in terms of creating a vibrant multicultural study environment as well as of various stakeholders’ expectations of what the higher education institutions should deliver regarding knowledge, skills and qualities that future professionals should have. Knight (2015) defined internationalization in higher education as „the process of integration of international, intercultural, or global dimensions into the purpose, functions or delivery of postsecondary education”. According to Knight and De Wit (2018, p. 2), „internationalization has evolved from a marginal and minor component to a global, strategic, and mainstream factor in higher education”. This results in intercultural diversity being tangled in the purpose, functions and delivery of higher education. Accordingly, students need to learn how to effectively work and live in such an environment and use the opportunity to prepare for culturally diverse workspaces.

„The development of culturally competent students” (Deardorff 2006, p. 241) is an important goal of internationalization of higher education, because „increasing globalization, workforce mobility, and international assignments are creating demand for culturally adept employees” (Ramsey and Lorenz 2016, p. 79). The significance of intercultural competences (ICC) in organizational settings was also elaborated on by researchers like Earley and Peterson (2004), Fischer (2011), and Podsiadlowski et al. (2013).

Internationalization, the resulting diversity and the need for ICC are also driven by the increasing competition in the higher education industry (Engwall 2016; Nada and Araújo 2019; Rust and Kim 2012), accreditation bodies’ requirements (e.g., EFMD Quality Improvement System), or government strategies (e.g., Internationalisation of Swedish Higher Education Institutions).

1.1 The problem and the purpose

Diversity is an appealing idea and it is easy to argue its benefits, which range from the general view that it „enriches each of us” (Liu, Volčič and Gallois 2019, p. 16), to more business-focused ones, such as „increased creativity, productivity, and quality” (Stevens, Plaut and Sanchez-Burks 2008, p. 118). However, Roberge and Van Dick (2010, p. 295) concluded that „many studies have found that diversity leads to negative consequences such as rising conflicts or decreasing group cohesiveness”. Stahl et al. (2010) confirmed that the negative effects of multicultural teams are dominant topics in literature.

Trice (2003) and Leask (2009) reported on the segregation of student groups and reducing possibility of interaction and cooperation. Negative experiences resulting from challenging group work further fortify cultural stereotypes (Harisson and Peacock 2009; Zhang et al. 2016). Students working in culturally diverse groups have to overcome many obstacles, including communication problems, reconciling different values, varying perceptions of time, responsibility, or different understanding of group work.

A frequent assumption is that exposure to different cultures automatically leads to enhanced ICC, but this has been identified as a dangerous misconception by numerous scholars (Jackson 2015; Lokkesmoe, Kuchinke and Ardichvili 2016; Ramsey and Lorenz 2016; Wang and Kulich 2015; Zhang et al. 2016). Bennett (as cited in Manzitti 2016) pointed out that „We sometimes mistakenly think that diversity in and of itself is valuable, but it’s not, it’s actually more problematic.” Anecdotal evidence from the classroom and content analysis of the course evaluations confirm that there is resistance toward culturally diverse groups.

„I like diverse groups and I highly appreciate the idea behind it, but…” (anonymous student, course evaluations 2019)

„International groups make little sense anyway…” (anonymous student, course evaluations 2018)

„…putting people of such different cultures together is not always a good idea… simply because the cultures are so far apart.” (anonymous student, course evaluations 2017)

Scholars agree that ICC is significant and very much needed. However, according to Deardorff (2015), despite great interest and a plethora of research in the field, some cardinal issues that still require further attention: – concept definition(s), development of ICC, and ICC assessment.

Accordingly, this paper focuses on understanding the concept of ICC from the perspective of business graduates and senior-year students at an international business school. The interest lies in collecting thoughts and feelings that describe their intercultural experience, and the assessment of their ability to reach goals in such a setting. By understanding how they perceive intercultural encounters, the researchers hope to be able to better understand what is necessary to design courses in order to promote and enhance ICC.

2 Theoretical background

The focus of this study makes it necessary to address the concept of ICC and discuss previous research and insights on course design with the purpose of enhancing ICC.

2.1 Intercultural competences

There is no single, universally accepted definition of the ICC concept, and concepts appear in literature under various names. Deardorff (2006, 2015, 2020), Griffith et al. (2016), Jackson (2015), Pinto (2018), and Wang and Kulich (2015), used the term „intercultural competence”. Bartel-Radic and Giannelloni (2017), and Ramsey and Lorenz (2016) preferred the term „cross-cultural competence”; while Lokkesmoe et al. (2016) have mentioned „intercultural competence”, „cross-cultural competence” and „global competence” in their work. Sinicrope, Norris and Watanabe (2007) listed almost 20 different concepts that are related to enhancing the efficiency and effectiveness of interaction in a culturally diverse setting.

A broad, encompassing definition claims that „intercultural competences are about improving human interactions across the difference, whether within a society (differences due to age, gender, religion, socio-economic status, political affiliation, ethnicity and so on) or across borders” (Deardorff 2020, p. 5). As a complex phenomenon, ICC might be based on:

- intercultural traits (open-mindedness, tolerance for ambiguity, flexibility, patience);

- intercultural attitudes and worldviews (ethnocentric-ethnorelative, cosmopolitanism);

- intercultural capabilities, such as communication, linguistic skills, social flexibility, and knowledge of other cultures (Leung, Ang and Tan 2014).

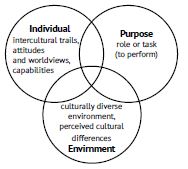

Analyzing multiple definitions of the concept (Griffith et al. 2016), the theory of action and job performance are adapted (Boyatzis 2008) and combined with the general framework of intercultural effectiveness (Leung et al. 2014) to capture three identified themes in these definitions: the need for ICC that facilitates successful performance of a role or a task in an environment where cultural differences exist (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Context, skills and the purpose of ICC

Source: Authors

2.2 Learning (or acquiring) intercultural competences

There is wide agreement among authors that ICC can be enhanced, and that its development is a lifelong process, rather than a measurable end-point (Deardorff 2015; Reichard et al. 2015). The development of ICC can occur in different formal and informal settings (Leask 2009). This research focuses on the formal course setting, involving course structure, content, activities and assignments.

There is evidence that, among other learning formats, courses can support the development of ICC. Fischer (2011) confirmed that course design with incorporated intercultural training resulted in increased cultural awareness. Eisenberg et al. (2013) reported a positive impact of a cross-cultural course on cultural intelligence. Jackson (2015) created an elective course focusing on intercultural transition, which resulted in increased ICC. Wang and Kulich (2015) designed a course centering on intercultural interaction and reflection on the experience that resulted in increased ICC.

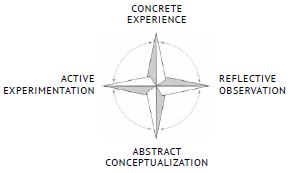

Analyzing previous research, experiential learning was found to be a common concept used across different course designs. If „culture is experienced” (Valentine and Cheney 2001, p. 92), then experiential learning is seen as facilitating „connection between knowledge gained in the classroom and its application in real life” is a relevant tool. Kolb and Kolb (2005) discussed the four stages of learning in experiential learning design (see Figure 2) that have been applied in the context of the designing courses with the underlying motive to enhance ICC.

Figure 2: The experiential learning cycle

Source: adapted from Radford, Hunt and Andrus (2015)

Experiential learning considers learning to be a process that includes relearning and conflict resolution, and it happens in the interaction between individuals and the environment. This resembles the process of enhancement of ICC, where there is „assimilation of new experiences into existing concepts and accommodating existing concepts to new experience” (Kolb and Kolb 2005, p. 194).

To create meaningful learning experiences, the point made by Leung et al. (2014, p. 508) can be used – namely, that most of the learning is happening in „direct, on-the-job experiences”. Thus, creating a course context that supports such conditions should be beneficial for ICC enhancement. Zhang et al. (2016) suggested using campus diversity as an asset, creating an environment that might reflect future business/workspace situations. An intercultural environment can be embedded as group work assignments facilitating interaction between students with different cultural backgrounds. Following the intergroup contact hypothesis, „it has been found that these positive effects of intergroup contact are most prominent when intergroup contact takes place in an environment that fosters (a) common goals, (b) equal status, and (c) intergroup cooperation” (Bocanegra, Markeda and Gubi 2016).

3 Method

After the literature review, a survey was designed to capture self-reflections from former students (master graduates) and current students in their final year of studying at an international business school. The survey, which contained mainly open-ended questions, was anonymous and administered through Qualtrics using purposive sampling. A total of 42 responses were collected, with students being personally approached via LinkedIn. Three responses were eliminated from further processing due to lack of responses. The content analysis was performed identifying major themes as well as an online word frequency counter to be able to spot patterns. The research instrument (see Table 1) was partly built on the Assessment Framework for Intercultural Competence in Higher Education by Griffith et al. (2016) and the research design presented by Arasaratnam and Doerfel (2005).

| BLOCK | Questions | Description |

|---|---|---|

| I | Q1 – Q6 | Demographic data – degree, gender, nationality, age; |

| II | Q7 – Q10 | Five-point Likert scale self-assessments: exposure to other cultures in academic and work environment, significance of ICC for future, and open-ended question on own understanding of the concept of intercultural competence; |

| III | Q11 – Q13 | Three open-ended questions relating to thoughts and feelings associated with intercultural encounters, together with perceived efficiency and effectiveness of reaching goals within multicultural team; |

| IV | Q14 – Q15 | Open-ended questions that asked respondents to profile a person considered to be interculturally competent and to provide a self-assessment; |

| V | Q16 – Q17 | Suggestions and ideas for improvement of ICC in the university setting. |

Table 1: Research instrument overview

Source: Authors

The research was performed at an international business school known for high mobility among students and faculty, resulting in high diversity at campus. During the last five years, master programs have had an average of 65% foreign students, while foreign students’ participation in bachelor programs increased from 22% in 2015 to 39% in 2019. Both authors are part of an internal project called Learning Across Borders, which was initiated to investigate the expectations and needs of different stakeholders related to internationalization and ICC.

4 Preliminary findings

All respondents reported exposure to other cultures during their studies and in their line of work, and almost unanimously agreed that the significance of ICC would increase over time. The sample consisted of 28 master students who had already graduated and 11 students in their final study year, most of who are either employed or working part-time. The group included 18 different nationalities, consisting mostly of German, Dutch and Swedish individuals.

In search for a contextualized definition of ICC, respondents were asked to give their own perception of the concept. Three themes were identified: environment/situation where the ICC is relevant, the purpose of ICC, and mechanisms instrumental for the purpose. Business graduates define ICC in the context of existing cultural differences as the purposeful ability that enables them to work with others, which is facilitated through knowledge, understanding, communication, and respect. This is in line with the definition proposed by Deardorff (2020), and the theoretical frameworks presented by Boyatzis (2008) and Leung et al. (2014).

When asked about intercultural interactions/collaborations, the respondents mainly connected this to goal-oriented behavior in an academic or work environment, with several respondents emphasizing the necessity to find a common ground in order to be able to work together. This is relevant for this study’s purpose, embedding the enhancement of ICC in the course design, following recommendations by Bocanegra et al. (2016), Leung et al. (2014), and Leask (2009, p. 205) to create a group assignment that facilitates „meaningful interaction between students from different cultural and linguistic backgrounds in and out of the classroom”.

Respondents emphasized the following differences: approach to the problem, behavior in general, dealing with stress or conflict, different approaches to leadership, attitudes toward time, and ambition. They stated that bridging these differences can be achieved through understanding, communication and patience. Some respondents claimed that self-awareness and reflection on one’s own culture is also important for being able to understand other cultures:

„if you realize your own culture and how you act in a group, I believe that you can more easily adapt and understand other cultures.” (Respondent MS25)

Another identified theme relating to cultural differences is a need to treat everyone with respect and achieve „equality with the difference” (Respondent MS24) or, to paraphrase, equality despite the difference.

In the responses, it is possible to identify both negative and positive thoughts/feelings toward intercultural experiences. The positive associations remain very general: learning, novelty, inspiration, broadening of minds, multiple perspectives and synergy, as captured by Respondent BS26, „enhances thinking outside the box”. Considering the research by Stahl et al. (2010), it is no surprise then when talking about negative aspects, the focus is narrower, more specific, and respondents connect explicitly some nations and experienced challenges, misunderstandings, frustration, stress and conflicts. Some participants reported that multicultural groups may underperform due to cultural differences.

Communication and language barriers were emphasized as one of the main issues: Respondent MS08 exemplified, „…message sent is not message received”; or Respondent BS35, „…I had no clue how much can be interpreted differently by people from different countries.” Communication is emphasized extensively in literature as one of the key factors of ICC. Respondents agreed on the time-consuming nature of intercultural interactions/work. Extra time is needed to compensate for communication difficulties and for different perceptions of deadlines and time. Therefore, topics dealing with differences in communication patterns (e.g., high- and low-context cultures, direct and indirect languages/cultures, pattern of communication, etc.) need to be introduced in a course content. Likewise, it is important to ensure realistic time frames for the assignment’s process and delivery.

The sample’s overall sentiment toward intercultural cooperation is positive, with a general good understanding of potential perils and obstacles – „difficult and frustrating, but rewarding when you ‘get it’” (Respondent MS10). There is a general agreement that the academic environment and education can significantly contribute to the development of ICC, encapsulated in the statement:

„…there are things that can be taught theoretically and other that have to be lived or experienced”. (Respondent MS16)

In line with a didactive approach to intercultural training (Graf 2003), respondents are suggesting more emphasis be placed on the delivery of content from instructors/experts on topics of culture and intercultural interactions, contributing to building a knowledge base and awareness of the scope of the topic. A second argument is creating more opportunities to experience intercultural interactions and build ICC. The suggestions range from exposure to cultures (e.g., exchange semesters or cultural fairs), to creating experiences where people from different cultures will have the opportunity to work together and provide context, guidance and assessment through such experiences.

According to Leask (2009), embedding ICC in the formal curriculum design should be guided by meticulous course design that promotes interaction and learning from it as well as requires teaching staff with necessary knowledge. It is important to bear in mind that this experience can be stressful for students with increased perception of risk of failure.

5 Practical implications

The purpose of the paper is to showcase a course design based on acquired insights from students, supported by available previous research, in order to enhance ICC within a formal higher education setting. While the primary focus was on a business school, this paper argues that principles of learning experience design for ICC can be applied in education in general.

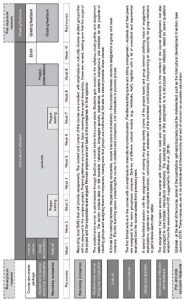

The case course is Applied International Marketing, which is offered in the second semester for two master programs: International Marketing and Strategic Entrepreneurship. The course had an average of 70 students from approximately 20 different countries in the last five years. The majority of students come from Germany, the Netherlands and China, while Swedish students are usually a minor group.

The compulsory component of the course is group work for Swedish small and medium size enterprises in the initial stages of internationalization, where student teams are assigned to perform initial market screening and provide ideas related to the advancement to a foreign market for their host company. Following recommendations by Bocanegra et al. (2016), Jackson (2015) and Leung et al. (2014), the intention was to create life-like experiences that would mobilize the diverse group around a common and challenging goal. For a detailed course timeline and structure, see Figure 3.

Experiential learning makes the learner engaged, responsible for own learning, which makes it suitable to deal with complex issues in context (Radford et al. 2015). This paper argues that ICC is a complex issue best addressed in the context of intercultural interaction.

Figure 3: Applied international marketing course description and timeline

Source: Authors

With the course design, the intention was to create a „learning space” defined by Kolb and Kolb (2005, p. 200) as a „construct of person’s experience in the social environment”. The course design is instrumental to securing various dimensions of learning (see Figure 2) linked to the course design, intended to secure learning of the disciplinary content (professional knowledge) as well as impacting ICC (as a soft skill):

- Abstract conceptualization: involves introducing the theoretical concepts relevant for ICC; increasing knowledge about culture and diversity; providing theoretical frameworks for categorizing cultures; ensuring awareness of the impact of culture on behavior, communication and group dynamics.

- Concrete experience: the actual exposure to work and collaboration within a culturally diverse group – this learning process is secured mainly through group assignment – company-driven project; this encompasses work in the classroom, but also interactions outside in organizing and delivering work.

- Reflective observation: is facilitated through structured reflections on intercultural experiences. The reflection is formatted according to the ICC assessment framework by Griffith et al. (2016). Learners are encouraged to create their own take-outs and actively evaluate their experiences.

- Active experimentation: is an opportunity for the learner to test acquired knowledge, and as Li and Armstrong (2015, p. 423) concluded, „…active experimentation both completes the cycle of learning and ensures that it begins anew by assisting the creation of new experiences”.

Learning processes are not linear. Phases, or different ways of learning, have a profound influence on each other. The course evolved over time with the intention of combining the didactic and experiential approach (Graf 2003), as well as of using the principles of constructivist learning (Bada 2015) suitable for learning complex skills, within heterogenous groups, by means of promoting social and communication skills through collaboration and exchange of ideas.

The presented course is a living laboratory, giving the opportunity to experiment with different elements of course design to enhance students’ ICC. Gradually, over the years, intercultural interaction was introduced into the course and became one of the focal themes. As a proxy of students increased focus on international encounters, it can be reported that the volume of text in the course evaluations, which can be directly or indirectly connected to intercultural issues and perspectives, increased almost 30 times in 2019 compared to 2015.

6 Conclusion

The multicultural workspace is becoming a standard, resulting in a need to enhance ICC as a transversal learning outcome (Pinto, 2018). Transversal competences are „competences that have the special feature of being transferable to any area of knowledge” (Sá and Serpa 2018, p. 3) and they have critical role in employability nowadays. Furthermore, in the contemporary job market, „general skills and personal qualities are considered at least as important as professional qualifications” (Illeris, 2003, p. 397). This paper strives to enhance students’ communication skills, problem-solving, creativity, leadership and – as part of these universal, soft skills – ICC. Responsibility for the development of these skills does not rest on a single educator, or a lecture or isolated event, but needs to be embedded as a guiding value in the way courses and programs are designed and delivered.

Advancements in technology, transportation, communication, as well as the mobility of people and ideas are without precedent in human history. If there is agreement on these facts, time and effort might need to be invested in to enhance individuals’ ability to work together with people of different cultural backgrounds. Higher education is international not because it is diverse, but because students can utilize diversity to enhance their lives and the lives of those around them.

Literatúra/List of References

- Arasaratnam, L. A. and Doerfel, L. M., 2005. Intercultural communication competence: Identifying key components from multicultural perspectives. In: International Journal of Intercultural Relations. 2005, 29(2), 137-163. ISSN 0147-1767.

- Bada, S. O., 2015. Constructivism learning theory: A paradigm for teaching and learning. In: Journal of Research and Method in Education. 2015, 5(6), 66-70. ISSN 1743-727X.

- Bartel-Radic, A. and Giannelloni, L. A., 2017. A renewed perspective on the measurement of cross-cultural Competence: An approach through personality traits and cross-cultural knowledge. In: European Management Journal. 2017, 35(5), 632-644. ISSN 0263-2373.

- Bocanegra, J. O., Newell, L. M. and Gubi, A. A., 2016. Racial/ethnic minority undergraduate psychology majors’ perceptions about school psychology: Implications for minority recruitment. In: Contemporary School Psychology. 2016, 20(3), 270-281. ISSN 0361-476X.

- Boyatzis, R. E., 2008. Competencies in the 21st century. In: Journal of Management Development. 2008, 27(1), 5-12. ISSN 0262-1711.

- Deardorff, D. K., 2006. Identification and assessment of intercultural competence as a student outcome of internationalization. In: Journal of Studies in International Education. 2006, 10(3), 241-266. ISSN 1028-3153.

- Deardorff, D. K., 2015. Intercultural competence: Mapping the future research agenda. In: International Journal of Intercultural Relations. 2015, 48, 3-5. ISSN 0147-1767.

- Deardorff, D. K., 2020. Manual for developing intercultural competencies. London: Routledge. 2020. [online]. [cit. 2020-01-24]. Available at: <https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429244612>

- Earley, P. Ch. and Peterson, S. R., 2004. The elusive cultural chameleon: Cultural intelligence as a new approach to intercultural training for the global manager. In: Academy of Management Learning & Education. 2004, 3(1), 100-115. ISSN 1537-260X.

- Eisenberg, J., Lee, J. H., Brück, F., Brenner, B., Claes, T. M., Mironski, J., and Bell, R., 2013. Can business schools make students culturally competent? Effects of cross-cultural management courses on cultural intelligence. In: Academy of Management Learning & Education. 2013, 12(4), 603-621. ISSN 1537-260X.

- Engwall, L., 2016. The internationalization of higher education. In: European Review. 2016, 24(2), 221-231. ISSN 10627987.

- Fischer, R., 2011. Cross-cultural training effects on cultural essentialism beliefs and cultural intelligence. In: International Journal of Intercultural Relations. 2011, 35(6), 767-775. ISSN 0147-1767.

- Graf, A., 2004. Assessing intercultural training cesigns. In: Journal of European Industrial Training. 2004, 28(2/3/4), 199-214. ISSN 0309-0590.

- Griffith, R. L., Wolfeld, L., Armon, K. B., Rios, J. and Liu, L. O., 2016. Assessing intercultural competence in higher education: Existing research and future directions. In: ETS Research Report Series. 2016, (2), 1-44. ISSN 2330-8516.

- Harrison, N. and Peacock, N., 2010. Cultural distance, mindfulness and passive xenophobia: Using integrated threat theory to explore home higher education students’ perspectives on ‘internationalisation at Home.’ In: British Educational Research Journal. 2010, 36(6), 877-902. ISSN 1469-3518.

- Illeris, K., 2003. Towards a contemporary and comprehensive theory of learning. In: International Journal of Lifelong Education. 2003, 22(4), 396-406. ISSN 1464-519X.

- Jackson, J., 2015. Becoming interculturally competent: Theory to practice in international education. In: International Journal of Intercultural Relations. 2015, 48, 91-107. ISSN 0147-1767.

- Knight, J., 2015. Updated definition of internationalization. In: International Higher Education. 2015, 33(3), 2-3. ISSN 2151-0393.

- Knight, J., and de Wit, H., 2018. Internationalization of higher education: Past and future. In: International Higher Education. 2018, (95), 2-4. ISSN 2151-0393.

- Kolb, A. Y. and Kolb, A. D., 2005. Learning styles and learning spaces: Enhancing experiential learning in higher education. In: Academy of Management Learning & Education. 2005, 4(2), 193-212. ISSN 1537-260X.

- Leask, B., 2009. Using formal and informal curricula to improve interactions between home and international students. In: Journal of Studies in International Education. 2009, 13(2), 205-221. ISSN 1028-3153.

- Leung, K., Ang, S., and Tan, L. M., 2014. Intercultural competence. In: Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior. 2014, 1(1), 489-519. ISSN 2327-0608.

- Li, M. and Armstrong, J. S., 2015. The relationship between kolb’s experiential learning styles and big five personality traits in international managers. In: Personality and individual differences. 2015, 86, 422-426. ISSN 0191-8869.

- Liu, S., Volčič, Z. and Gallois, C., 2019. Introducing intercultural communication: Global cultures and contexts. London: Sage, 2019. ISBN 9781526431707.

- Lokkesmoe, K. J., Kuchinke, P. K. and Ardichvili, A., 2016. Developing cross-cultural awareness through foreign immersion programs: Implications of university study abroad research for global competency development. In: European Journal of Training and Development. 2016, 40(3), 155-170. ISSN 2046-9012.

- Manzitti, V., 2016. Bringing intercultural competence to development. 2016. [online]. [cit. 2019-11-17]. Available at: <https://europa.eu/capacity4dev/article/bringing-intercultural-competence-development>

- Nada, C. I. and Araújo, C. H., 2019. When you welcome students without borders, you need a mentality without borders’ internationalisation of higher education: Evidence from Portugal. In: Studies in Higher Education. 2019, 44(9), 1591-1604. ISSN 0307-5079.

- Pinto, S., 2018. Intercultural competence in higher education: Academics’ perspectives. In: On the Horizon. 2018, 26(2), 137-147. ISSN 1074-8121.

- Podsiadlowski, A., Gröschke, D., Kogler, M., Springer, C. and van der Zee, K., 2013. Managing a culturally diverse workforce: Diversity perspectives in organizations. In: International Journal of Intercultural Relations. 2013, 37(2), 159-175. ISSN 0147-1767.

- Radford, S. K., Hunt, M. D. and Andrus, D., 2015. Experiential learning projects: A pedagogical path to macromarketing education. In: Journal of Macromarketing. 2015, 35(4), 466-472. ISSN 0276-1467.

- Ramsey, J. R., and Lorenz, P. M., 2016. Exploring the impact of cross-cultural management education on cultural intelligence, student satisfaction, and commitment. In: Academy of Management Learning & Education. 2016, 15(1), 79-99. ISSN 1537-260X.

- Reichard, R. J., Serrano, A. S., Condren, M., Wilder, N., Dollwet, M. and Wang, W., 2015. Engagement in cultural trigger events in the development of cultural competence. In: Academy of Management Learning & Education. 2015, 14(4), 461-481. ISSN 1537-260X.

- Roberge, M. É. and van Dick, R., 2010. Recognizing the benefits of diversity: When and how does diversity increase group performance? In: Human Resource Management Review. 2010, 20(4), 295-308. ISSN 1053-4822.

- Rust, V. D. and Kim, S., 2012. The global competition in higher education. In: World Studies in Education. 2012, 13(1), 5-20. ISSN 1441-340X.

- Sá, M. J. and Serpa, S., 2018. Transversal competences: Their importance and learning processes by higher education students. In: Education Sciences. 2018, 8(3), 1-12. ISSN 2227-7102.

- Sinicrope, C., Norris, J. and Watanabe, Y., 2007. Understanding and assessing intercultural competence: A summary of theory, research, and practice (Technical teport for the foreign language program evaluation project). In: Second Language Studies. 2007, 26(1), 1-58. ISSN 2542-3835.

- Stahl, G. K., Mäkelä, K., Zander, L. and Maznevski, L. M., 2010. A look at the bright side of multicultural team diversity. In: Scandinavian Journal of Management. 2010, 26(4), 439-447. ISSN 0956-5221.

- Stevens, F. G., Plaut, C. V. and Sanchez-Burks, J., 2008. Unlocking the benefits of diversity: All-inclusive multiculturalism and positive organizational change. In: The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science. 2008, 44(1), 116-133. ISSN 0021-8863.

- Trice, A. G., 2003. Faculty perceptions of graduate international students: The benefits and challenges. In: Journal of Studies in International Education. 2003, 7(4), 379-403. ISSN 1028-3153.

- Valentine, D. and Cheney, S. R., 2001. Intercultural business communication, international students, and experiential learning. In: Business and Professional Communication Quarterly. 2001, 64(4), 90-104. ISSN 2329-4906.

- Wang, Y. A. and Kulich, J. S., 2015. Does context count? Developing and assessing intercultural competence through an interview- and model-based domestic course design in China. In: International Journal of Intercultural Relations. 2015, 48, 38-57. ISSN 0147-1767.

- Zhang, M., Xia, J., Fan, D. and Zhu, J., 2016. Managing student diversity in business education: Incorporating campus diversity into the curriculum to foster inclusion and academic success of international students. In: Academy of Management Learning & Education. 2016, 15(2), 366-80. ISSN 1537-260X.

Kľúčové slová/Key words

cultural diversity, manager education, living laboratory, mobility of students, self-reflection assignment

kultúrna rôznorodosť, vzdelávanie manažérov, živé laboratórium, mobilita študentov, sebareflexné zadanie

JEL klasifikácia/JEL Classification

I23, M14, M31

Résumé

Vzdelávanie budúcich manažérov pre kultúrne rozmanitý pracovný priestor: Využívanie kurzu ako živého laboratória

Spoločnosť sa čoraz viac stáva multikultúrnou a rastie tlak na zvyšovanie kvality medzikultúrnych interakcií. Inštitúcie vysokoškolského vzdelávania zažívajú internacionalizáciu prostredníctvom zvýšenej mobility študentov a učiteľov, čo vytvára potrebu riadenia rozmanitosti s nevyhnutnosťou hladkej komunikácie, znižovania stresu a zefektívňovania štúdia a práce v multikultúrnom prostredí. Zamestnávatelia tiež diktujú potrebu vychovávať kultúrne schopných odborníkov, ktorí sú schopní uspieť v globalizovanom prostredí charakterizovanom zvýšenou mobilitou pracovnej sily a medzinárodnými úlohami. Diskusia o medzikultúrnych kompetenciách má u výskumných pracovníkov a odborníkov z praxe dlhú cestu bez akejkoľvek dohody o jej definícii alebo meraní, ale má jasný odkaz, že kultúrna rozmanitosť nebude mať za následok zvýšenie interkultúrnych kompetencií. V tomto príspevku sa interkultúrne kompetencie považujú za prierezový vzdelávací výsledok, berúc do úvahy rastúcu internacionalizáciu vysokých škôl. Prieskum je svojou povahou kvalitatívny, založený na analýze hodnotení kurzov a na otvorenom prieskume. Táto štúdia použila účelovú vzorku súčasných i bývalých študentov, ktorí boli počas štúdia na medzinárodnej podnikateľskej škole vo Švédsku vystavení rôznorodému interkultúrnemu prostrediu. Na základe zistení sa navrhuje kurz, v ktorom majú študenti pracovať na zadaní v kultúrne rozmanitom tíme. Komponenty kurzu založené na prednáškach sú vyvážené pridaním komponentu sebareflexného zadania, ktorý poskytuje kultúrne špecifické aj všeobecné vedomosti, čím prispieva k schopnosti extrapolovať skúsenosti pri budúcich medzikultúrnych stretnutiach.

Recenzované/Reviewed

29. March 2021 / 6. April 2021