1 Introduction

Sustainable consumption plays a profound role for achieving global sustainability, as exemplified by goal 12 of the Sustainable Development Goals of the United Nations (United Nations General Assembly 2015). However, the role of consumer behavior for achieving sustainable consumption is yet to be fully determined. One of the most prominent examples of the ambiguous role of consumers is how little sustainable purchase intentions translate to sustainable behavior; the so-called attitude-intention-behavior gap (e.g., Elhaffar et al. 2020; Park and Lin 2020; Conner and Norman 2022). Numerous scholars have highlighted how different factors such as intention strength (Conner and Norman 2022), product availability and perceptions of effectiveness (Nguyen et al. 2018), or subjective norms (Park and Lin 2020) impact the scope of this gap. Whether a sustainable transformation can be achieved on an individual level is thus still up for debate.

Nevertheless, despite a broad and mature body of literature on how to scale down the gap to hold consumers accountable for their impact, Elhaffar et al.’s (2020) review has called for investigating further factors. Particularly, antagonistic dimensions (e.g., egoistic/hedonistic versus altruistic values) have been called into further investigation (Elhaffar et al. 2020, 10).

In this article, we thus aim to quantitatively scrutinize opposing effects to better understand factors that promote and prevent sustainable consumption. To achieve this, we chose smartphones as a consumer good in Germany as (1) smartphone use is widespread throughout the globalized world; (2) it’s comparatively high price on the one hand, and technological advances on the other entail opposing incentives regarding the service life; and (3) we expect a high access to information of consumers, which is reinforced by the impact of technology for sustainable consumption.

We begin by briefly referring to the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB; Aizen 1991), as it is arguably the most common and suitable lens (Yuriev et al. 2020). Subsequently, we present antagonistic, intrapsychic factors we deem influential and derive five core hypotheses based on the literature. After a brief outline of our methodology and sample, we highlight significant and non-significant findings and contextualize these within the TPB in our discussion. We conclude by carving out limitations and future research opportunities.

2 Theoretical framework

2.1 Relation to the theory of planned behavior

Much research from different fields has investigated the role of the attitude-intention-behavior gap. We follow the fourfold conceptualization of Elhaffar et al. (2020, 4) into (1) „modelling the gap“ by highlighting opposing factors; (2) „methodological bias“ due to a lack of rigorous methods; (3) prioritizing the self over the environment; and (4) coping with the gap post decision-making. The factors investigated in our study fall into the intersection of modelling the gap and prioritizing the self over the environment. Both conceptualizations have provided numerous intriguing avenues for research while arguably overlapping. For instance, depending on personal identity and attitude, sustainable consumption can either be seen as something conflicting with other values (i.e., as an intrapsychic factor), or enhancing the self (i.e., a prioritization of the self) (Martenson 2018).

The theory of planned behavior (TPB; Aizen 1988, 1991, 2020) is commonly used to understand the interplay of intentions versus behavior (Yuriev et al. 2020). According to this theory, 1) the attitude towards the behavior, 2) the existing subjective norms and 3) the perceived control over one’s own behavior lead to behavioral intentions, which in turn result in the individual’s behavior. However, TPB has been heavily criticized in other fields of research (Hardemann et al. 2002; Sniehotta et al. 2014). We expand TPB to our specific case by replacing the dependent variable (behavior) with pro-environmental behavior. This allows the conceptual model to capture different sustainable behaviors such as upcycling, an extended period of usage, or voluntary nonconsumption (Li et al. 2019; Park and Li 2020, Santor et al. 2020; Weitensfelder et al. 2023). Further, we broaden „intention“ to represent not only the intention for a sustainable usage of smartphones, but rather the more general intended usage. This expanded conceptualization allows us to better model the contemporary meaning of smartphones as roughly 80 percent of adults in Western societies use theirs regularly and for a wide variety of tasks (Olsen et al. 2022).

Some elements of the TPB remain unconsidered by us. Control over one’s own behavior and potential outcomes is a central independent element of the TPB. For example, it may be that certain behavioral intentions (e.g. waste separation) cannot be practiced at all (e.g. in the absence of a separate public collection system). Similar to many other studies (cf. Sheeran 2020, 10), perceived behavioral control is not taken into account in our approach, as users definitely have control over our indicators for PEB (duration of use, repair attempts). Furthermore, in contrast to the TPB, we refrain from measuring social pressure and the resulting social norms. The extent to which there is a connection between the public discussion about the need for social reorientation and the norms of the individual would have to be examined in terms of learning theory, which is not the focus of our study.

2.2 Theoretical propositions

Empirical research has illustrated numerous problems in the assumption that intention translates to behavior (Sheeran and Webb 2016). We have thus adapted our model to represent an intention towards the product itself. Schifferstein/Zwartkruis-Pelgrim have proposed the concept of consumer-product attachment, which describes „the strength of the emotional bond a consumer experiences with a durable product“ (Schifferstein/Zwartkruis-Pelgrim 2008, 1). Attachment is based on cognitive and emotional factors and influences distinct sustainability-related behaviors such as intentions to repair faulty parts, which in turn proliferates the service life of a product. We thus hypothesize that Attachment to a smartphone should influence pro-environmental behaviors regarding smartphone usage:

H1: Higher personal attachment (PA) to a smartphone in turn results in consumer

behavior aiming to proliferate the service life of that smartphone.

Furthermore, a rich body of literature has shown how specific personality traits shape buying behavior (Baumgartner 2002). Following this perspective, we chose exploratory buying behavior tendency (EBBT) as an antagonistic factor to PA. Baumgartner and Steenkamp (1996, 124) have defined EBBT as „those activities involved in the buying process (in the broadest sense) which are intrinsically motivated and whose primary purpose is to adjust actual stimulation obtained from the environment or through internal means to a satisfactory level“. While PA may increase service lives of smartphones, EBBT predicts initial purchases of newly developed products at the expense of existing products. Typical conceptualizations focus on consumers’ joy to investigate and try out new products. We thus hypothesize:

H2: Higher levels of EBBT result in more frequent purchases of smartphones and thus mitigates pro-environmental behavior.

The fact that there is widespread social pressure in western societies today to behave in an environmentally friendly and sustainable manner is a trivial finding (see e.g. Stankunie et al. 2020; De Canio et al. 2021). However, the question of whether this social pressure already influences consumers’ intentions for a future PEB is relevant. In the TPB, behavior is the consequence of the interaction of the independent variables of the past, which have an effect on current behavior via a developed behavioral intention. However, especially in the case of consumer goods that are in use for a long time, such as smartphones, it is possible that actual intentions will only be reflected in future purchase acts. We are therefore not only interested in the connection between past intentions and behavior up to the present, but also in the extent to which future behavioral intentions reveal a change compared to the behavior practiced to date. Due to the existing public pressure for environmentally oriented behavior, the more consumers have practiced non-environmentally oriented behavior in the past, the higher their tendency to change their behavior in the future should be. We therefore postulate:

H3.1: Consumers intend to reduce the future service life of their smartphone.

H3.2: The shorter the previous period of use of the smartphone, the greater the

intention to extend the period until a new purchase in the future.

In addition to public pressure to behave in an environmentally friendly manner, there may also be subjective pressure from the individual to own a state-of-the-art appliance. It has long been known (cf. Packard 1960) that manufacturers use all kinds of measures to stimulate individuals’ propensity to consume. One widespread measure is to create the impression of psychological obsolescence among consumers by frequently changing models in order to encourage them to buy new products. Psychological obsolescence occurs „when a product becomes less fashionable and unwanted due to newer trends… in the case of psychological obsolescence, the product is essentially fully functional“ (Becher/Sibony 2021, 104).

In the case of „functional“ or „absolute“ obsolescence (Cooper 2003, 423), i.e. the presence of predominantly technical reasons (appliance defective, no longer fully operational), a new purchase is not an indicator of consumers’ environmental orientation. But replacing a fully functional good solely due to its lack of trendiness or style indicates a deficient environmental consciousness in behavior.

The effect of this psychological obsolescence should be detectable in past consumer behavior as well as in future trends, we postulate accordingly:

H4.1: The greater the influence of psychological obsolescence, the less pronounced is the environmentally friendly behavior of consumers with smartphones.

H4.2: The greater the influence of psychological obsolescence, the less pronounced the tendency for consumers to behave in a more environmentally friendly way with their smartphones in the future.

In contrast, consumers who want to avoid the buying impulse from psychological obsolescence through conscious PEB will practice self-restraint in their consumption behavior:

H5.1: The more consumers want to practice self-restraint in consumption, the more pronounced is their pro-environmental behavior with smartphones.

H5.2: The more consumers want to practice self-restraint in consumption, the more pronounced the tendency towards environmentally friendly behavior with the smartphone in the future.

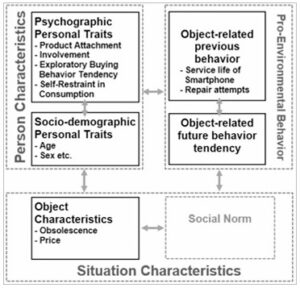

Figure 1 shows an overview of the key constructs of the present study, whereby it should be noted that we did not explicitly measure social norms.

Figure 1: Product-related PEB as a dependent of selected personal and situational constructs

Source: Authors

3 Empirical study

3.1 Research approach and design

A partially standardized approach was used to collect the relevant constructs. Open questions were used to determine whether and, if so, what experiences the respondents have had with prematurely defective products in the past three years and whether they had ever had something repaired on their smartphone. All other questions were surveyed quantitatively.

Pro-environmental behavior: We did not collect scales with opinions and judgments about what is desirable (see e.g. Santor et al. 2020; Wong et al. 2020), but wanted to measure PEB using the clearest possible behavioral indicators. As the main indicator for PEB, we use the service life of the smartphone, as a longer ownership cycle expresses a more sustainable behavior of consumers that is less harmful to the environment through waste. In response to the direct question „Can you please estimate how long you use a cell phone before you buy a new/another one?“, a usage period could be specified by entering months and years.

Another aspect of the PEB is the willingness to repair things when necessary (Kaitala et al. 2021). In this regard, we asked whether, how often and, if so, what consumers had already had repaired on their smartphone. For a high-quality and expensive consumer good, it is to be expected that consumers will consider repairs for minor defects; at the same time, the number of repair attempts can be understood as a quantitative indicator of PEB.

The intention to purchase new items more frequently in the future, as a further indicator of PEB, could not be measured on an interval scale, as in preliminary studies the respondents were unable to name a specific time period. However, they were able to name a behavioral tendency, so that a five-point ordinal index with the values (4=much more often, 3=somewhat more often, 2=just as often, 1=less often, 0=much less often) was used in the present study.

Psychological obsolescence: In a preliminary study, we had identified the five most important reasons for purchasing a new smartphone. In the main survey, respondents were asked how likely it was that they would change their device for these reasons. The items contain both functional and psychological reasons for obsolescence (see Table 2).

Self-restraint: In times of increasing awareness of sustainability in personal purchasing behavior, there is a widespread focus on the willingness to limit purchases to things that are really needed (Fuchs et al. 2021), i.e. a self-commitment to purchasing restraint (Weitensfelder et al. 2023). In connection with the TPB, the literature primarily attempts to describe and explain which factors contribute to the fact that environmentally oriented behavioral intentions are actually reflected in the concrete actions of individuals (Heeren et al. 2016; Yuriev et al. 2020) or which conditions and hindering factors lead to attitudes, intentions and concrete actions falling apart (Stankuniene et al. 2020; Graves et al. 2021). We do not intend to replicate this part of the research on sustainability (for summaries, see e.g. Yuriev et al. 2020; Weitensfelder et al. 2023). Occasionally, it is complained that the commitment to purchase restraint as an essential component of PBT has so far remained underexposed in the literature (Santor et al. 2020). Corresponding empirical measurement instruments are voluminous; for example, the consumption reduction questionnaire contains no fewer than 45 items, among them

„various elements of consumption restriction behavior, including an individual’s attitudes,

expectations, and perceived ability, as well as intentions to restrict consumption and actual“ (ibid., 5). We harbor skepticism towards intricate scales. In addition to a solitary construct, supplementary variables typically necessitate collection, resulting in excessively lengthy questionnaires that strain the capacity and inclination of the general populace to furnish information. Hence, we employed a one-item measure, validated in preliminary studies for its predictive efficacy, encapsulating consumer behavior among sub-target groups with the statement: I only buy things that I really need.

In addition to the behavior-related measurements, the willingness to pay for the purchase of a new appliance was also surveyed (in Euros, open question).

Consumer-product attachment was measured with reference to the consumer-product attachment questionnaire by Schifferstein/Zwartkruis-Pelgrim (2008). As this questionnaire with four dimensions and 28 items appeared too long for use in our larger study, we conducted two preliminary studies to determine how the 28 original items could be further reduced. In order to map the sub-dimensions proposed by the authors, we selected the two items for each of the four dimensions that had the highest factor loadings in exploratory principal component analyses, resulting in a subscale with a total of 8 items (see Table 3).

In the original study by Schifferstein and Zwartkruis-Pelgrim, 161 participants from a local community selected one of four predefined products (39 lamp, 38 clock, 40 car, 44 ornament) as reference points for their responses. To avoid further dividing our sample, given the assumed differences in attachment across product categories, we used the smartphone as the sole reference object. As a control variable to measure attachment, we assessed respondents’ involvement with a single-item measurement (question: How important is the smartphone for your personal life?).

Exploratory buying behavior tendency: EBBT was measured with reference to the

Baumgartner/Steenkamp approach. The authors differentiate between the sub-dimensions

exploratory acquisition of products (EAP) and exploratory information seeking (EIS), each

being measured with 10 items, using a scale from 1 (completely disagree) to 5 (completely agree). The authors’ final validation study included a sample of 320 American and 159 Dutch undergraduate students.

For our study, the focus was explicitly on real consumer behavior and less on aspects such as curiosity, attitude towards advertising materials, etc., as addressed in the EIS scale. We conducted a preliminary study with 154 respondents in which we used principal component analysis to check the dimensionality of the 20 items and finally selected three items with a clear behavioral reference that showed a high loading on the resulting main factor (see Table 4).

Other socio-demographic characteristics: To control for possible differences in subgroups, we collected 1) age (years), 2) gender (female, male, diverse), 3) the highest educational qualification achieved (Secondary school, middle school, high school diploma, university degree), 4) the presence of a migration background (yes, no) and 5) a self-assessment of residential location (I feel like a city dweller, I am a resident of small and medium-sized towns, I am a resident of rural areas).

Scaling level: We wanted to achieve interval scale levels for quantitative items in the resulting data material in order to avoid restrictions on the evaluation procedures to be used.

In order to convey a consistent survey concept, respondents should not be confronted with different answer specifications for different theoretical constructs. For all quantitative questions, we therefore chose the answer scale from 0 to 100, which corresponds to the percentage scale and the decimal system (example: Please tell me to what percentage you agree with the following statement: I like to try brands I don’t know …%). This scaling, which has proven successful in other studies by the authors, overcomes the arbitrariness of determining a distractor number, as is inherent in Likert scales with 5, 7 or 9 values. Furthermore, it does not require any verbalization for the distractors, which could be understood differently by respondents. It is understood intuitively and enables spontaneous response behavior without overwhelming the respondents (Lewis/Erdinc 2017). In practice, the scale from 0 to 100 corresponds to the decimal system (strictly speaking, it is an 11-point scale), as most respondents answer in steps of 10 when given the opportunity to enter their answers freely. It is becoming increasingly popular in research, as it can be easily implemented in online surveys with sliders (Cheung et al. 2018) and results in rather normally distributed (Leung 2011) and mostly easily analyzable data (cf. e.g. Riedl et al. 2023). In our study, the scale was implemented with a slider and a default setting of increments of 10, resulting in a scale that can assume values between 0 and 10, which we refer to below as the decimal scale.

3.2 Method and sampling

We surveyed a sample of 800 people in the first quarter of 2023 using an online survey.

Respondents were selected via convenience sampling with quotas for age, gender, education level, and migration background, ensuring the sample roughly represents the German population aged 18 and above. The incoming data records were checked for completeness, obvious incorrect entries, etc. in all variables. Ultimately, 744 data records were used for the analysis, which are made up as follows: The age range is between 18 and 93 years, average age 46.9 years (median 48); 49.7% are female, 50.3% male (0 diverse). 25.5% have a lower secondary school leaving certificate or no qualification, 23.8% have an intermediate school leaving certificate, 20.3% have a high school diploma (without intention to study), 30.4% are currently studying or have already completed a university degree. In terms of place of residence, 33.1% are rural residents, 46.8% are residents of small and medium-sized towns, and 20.2% are city dwellers. A total of 12.9% of respondents have a migration background.

3.3 Results

3.3.1 Period of use of smartphones

The smartphone usage data collected from test subjects underwent outlier analysis. The

resulting individual durations of smartphone use analyzed ranged from 6 to 102 months, with an average (mean) duration of 44.7 months (median 42). The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test rejects the normal distribution assumption, but a Q-Q diagram shows an acceptable approximation of the observed values to the expected normal values.

The duration of use exhibits a significant increase with advancing age (r=.40, p<.001), it is significantly lower among people with a migration background (mean 39.0) than among people without such a background (45.6 months, T=-3.137, p=.002, homogeneity of variance is given: Levene F=1.453, p=.228). There are no gender-specific differences, but there is a significant decrease in the duration of use with the size of the place of residence: residents of rural areas: 48 months, residents of small and medium-sized towns: 43.4 months, city dwellers 42.5 months (Anova: F=5.421, p=.005). Furthermore, people with a lower secondary school leaving certificate (mean 49.1 months) differ significantly from people with a) an intermediate school leaving certificate (42.1) and b) a university degree (41.8) (Tamhane test for a) p=.006, b) p=.001), while c) there is no significant difference to people with a high school diploma (46.6, p=.820).

Of all socio-demographic variables, age exerts the most significant influence on a longer period of use. Longer periods of use by people without a migration background, residents of rural areas and people with a lower level of education are partly due to the fact that they have a higher average age than the other groups.

3.3.2 Repair attempts

Only 38.7% of respondents report that they had already attempted or commissioned a repair. The maximum reported number of repair attempts is 4, the mean value of all respondents is .45. Of the reported repair attempts, display repairs account for 53.2% and battery replacements for a further 24.9% of all cases, meaning that these two processes together account for 85% of all repairs.

3.3.3 Intended future cycle of procurement

As Table 1 shows, in the original 5-level scaling, the two extreme values of the scale (much more often, much less often) are only mentioned by a few respondents. Combining the two answers that go in the same direction (column 3) results in more reliable cell assignments. As a result, 30.4 percent of respondents intend to buy a new appliance „less often“ in the future, which is more than three times as many as those who plan to buy more often.

| Will you buy a new smartphone more or less often in the future? | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Original responses | 1 Frequency | 2 Percent | Aggregated responses | 3 Percent |

| much more often | 2 | .3 | more often | 9.5 |

| somewhat more often | 69 | 9.3 | ||

| just as often | 447 | 60.1 | just as often | 60.1 |

| less often | 198 | 26.6 | less often | 30.4 |

| much less often | 28 | 3.8 | ||

| Total | 744 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

Table 1: Tendency towards future procurement behavior

Source: Authors

3.3.4 Obsolescence

When examining the dimensionality of the five items on obsolescence, the principal component analysis provides three dimensions, explaining 83.85% of the variance.

| Rotated component matrix | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Component | |||

| Probability reason for change: | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 8.1 I notice that my device is not up to date with the latest technology. | .501 | .644 | .223 |

| 8.2 I can't get the latest apps to work on the device. | .154 | .926 | .126 |

| 8.3 The device still works, but looks worn. | .864 | .135 | .179 |

| 8.4 There are already several new generations of this device. | .833 | .285 | .107 |

| 8.5 The battery has lost about a third of its original power. | .186 | .179 | .964 |

Extraction method: Principal components analysis. Rotation method: Varimax with Kaiser normalization.

Table 2: Loading structure of obsolescence items

Source: Authors

As the table shows, variables 8.1 and 8.2 form a „functional obsolescence“ dimension. 8.3 and 8.4 reflect the „psychological obsolescence“, i.e. the tendency of consumers to purchase a new device despite the existing device’s technical functionality. 8.5 reflects the loss of battery performance, i.e. the „defect“ of the smartphone most frequently mentioned in the open survey (without further presentation in this report) alongside display breakage.

Cronbach’s alpha provides a good reliability value of .75 for items 8.3 and 8.4. Based on the two items, we calculate a sum index „psychological obsolescence“, ranging from 0 to 9 on the decimal scale, with a mean value of 1.8, which expresses a low influence of psychological obsolescence in the self-perception of consumers (for comparison: mean battery: 4.7, median 5).

3.3.5 Consumer-product attachment

| Rotated component matrix | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Component | |||||

| Assignment of items to dimensions in Schifferstein et al. (2008) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| Attach-ment | Indispens- ability | (tech- nical) Irreplace- ability | Self- extension | ||

| Attachment | 11.1 This cell phone is very close to my heart. | .587 | .538 | -.152 | .000 |

| Indispensability | 11.2 I could live my life without this cell phone. (recod) | .800 | -.054 | .207 | .063 |

| Irreplace-ability | 11.3 Even a replacement device could not replace this cell phone for me. | .074 | .848 | .095 | .019 |

| Self- extension | 11.4 If I lost my cell phone, I would feel as if I had lost a part of myself. | .274 | .700 | -.024 | .255 |

| Attachment | 11.5 This cell phone means nothing to me. (recod) | .671 | .331 | .247 | -.022 |

| Self- extension | 11.6 If I had to describe myself, I would probably also mention the cell phone. | .082 | .134 | .041 | .967 |

| Indispens-ability | 11.7 This cell phone is absolutely essential for me. | .655 | .336 | -.150 | .191 |

| Irreplace-ability | 11.8 This cell phone is the same as another specimen of this model. (recod) | .121 | .029 | .951 | .038 |

Extraction method: Principal component analysis. Rotation method: Varimax with Kaiser normalization.

Table 3: Loading structure of attachment items

Source: Authors

Based on several explorative principal component analyses, a solution with four factors proves to be the best for the 8 items of Attachment. This basically corresponds to the expectation of four-dimensionality based on Schifferstein/Zwartkruis-Pelgrim and our own preliminary studies, but there are differences in the allocation of the items (see Table 3):

• In addition to the two items 11.1 and 11.5, items 11.2 and 11.7 are added to the attachment factor, which were originally intended to express „indispensability“.

• Items 11.3 (originally irreplaceability) and 11.4 (originally „self-extension“) form a new

factor that expresses something like a fear of loss or „personal irreplaceability“.

• Factor three is essentially generated from item 11.8, which expresses purely technical

interchangeability. Respondents obviously differentiate between purely technical replaceability and personal replaceability, as expressed in factor 2. This finding is consistent with the distinction between different forms of obsolescence in the literature (cf. e.g. Becher/Sibony 2021).

• Factor 4 consists exclusively of item 11.6, which originally means „self-extension“. However, such an extensive self-identification with the smartphone, as described in the wording of this item, seems excessive to the majority of respondents. This can be seen from the fact that the mean value of all respondents for this question on the 10-point scale is only .44, while the values for the other items are between 2.28 and 6.69.

Obviously, items 11.6 and 11.8 express something different for our test subjects than the attachment to the smartphone. In the case of 11.6, it is the purely technical interchangeability of an industrial mass product; in the case of 11.8, it is a self-definition of the individual via the device that is perceived as exaggerated and therefore rejected. We therefore decided to remove both items from the scale; as a result, Cronbach’s alpha increased from .735 to .775.

We again checked the dimensionality of the six remaining items. According to the Kaiser criterion, principal component analysis yielded one single factor with an eigenvalue of 2.857 and consistently high factor loadings between .58 and .77. We therefore finally calculated a reliable sum index for the subjects’ attachment from items 1, 2, 4, 5, 7 and 8. This variable yields values between .33 and 9.33 on the decimal scale for the sample, with a mean value of 3.9 (median 3.8).

Although Kolmogorov-Smirnov test (.046, p<.001) rejects the normal distribution assumption for the calculated attachment, the histogram of the data shows that the deviations from the normal distribution are small, with the exception of a slight shift to the left, so that further calculations with the attachment as an independent and dependent variable appear legitimate.

With an average value of 3.9, the absolute level of attachment is below expectations, as smartphones are considered high involvement products. Schifferstein/Zwartkruis-Pelgrim report attachment scores between 2.9 and 3.6 for their four product categories on the 5-point scale used, which, when converted to the decimal scale we use (for the conversion formula, see Riedl/Zips 2015, 40), would lead us to expect values between 4.75 and 6.5, with an average of 5.4.

Overall, due to the much larger sample size, we have confidence in the reliability of our data with regard to the smartphone test object. The reliability according to Guttman (item group a: 11.1, 11.2, 11.3, b: 11.4, 11.5, 11.7) provides a value of .811 (Amelang/Schmidt-Atzert 2006; Bühner 2021). We interpret the somewhat lower attachment found as meaning that consumers have become accustomed to the fact that, despite a high level of personal involvement with their smartphones, technical progress and the inevitable deterioration of technical components such as the battery make it almost unavoidable to part with their own device after a few years.

For the control variable Involvement, a high value of 7.18 was found on the decimal scale on average among the respondents. Unsurprisingly, involvement and attachment are significantly correlated (r=.506, p<.001).

3.3.6 Exploratory consumer buying behavior tendency

The dimensionality check yields two factors for the three EBBT variables, which together represent 79.2 percent of the initial variance. In line with the assignment in Bauga ner/Steenkamp, the items 12.1 and 12.4 taken from the EAP subscale load on one factor, while 12.2 (from EIS) loads on a second factor that relates more to information behavior.

| Rotated component matrix | ||

|---|---|---|

| Component | ||

| 1 | 2 | |

| 12.1 I like to try out new brands that I don't know. | .734 | .397 |

| 12.3 I like to find out about news in the retail sector. | .007 | .946 |

| 12.4 I am cautious when it comes to trying new products. (recod) | .865 | -.188 |

Extraction method: Principal component analysis. Rotation method: Varimax with Kaiser-normalization

Table 4: Factor loadings of EBBT Items

Source: Authors

We excluded item 12.3 and formed a sum index of EBBT from items 12.1 and 12.4 for use in subsequent analyses. This provides a mean value of 4.45 on the decimal scale for the total sample. Baumgartner/Steenkamp report values between 2.22 and 3.92 for the 20 items of the EBBT, on average 3.15 on the Likert scale from 1 to 5; when converted to the decimal scale we used, this would correspond to values between 2.75 and 6.57, on average 4.84.

For the EBBT calculated, the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test (p<.001) rejects the normal distribution hypothesis, but the Q-Q plot shows a high approximation to the expected distribution, so that serious distortions need hardly be assumed in further analyses.

3.3.7 Hypothesis testing

According to hypothesis 1, a higher level of attachment would lead us to expect a longer period of smartphone use. In fact, the regression analysis provides a significant (p<.001) but negative correlation (n=743, beta= -.246). This finding remains practically unchanged if the analysis is restricted to people who explicitly state that they obtain the smartphone themselves (n= 671, beta=-.249).

Due to this surprising finding, we checked the validity of the attachment measurement based on the correlation with third-party variables. This showed that attachment has the expected positive correlation with both involvement (r=.506, p<.001) and willingness to pay (r=.188, p<.001), so that a measurement problem appears to be ruled out.

We used the number of repair attempts practiced as an alternative indicator for PEB and also included the control variables mentioned above.

| Correlations (n=744) | Total number of repair attempts | |

|---|---|---|

| Pearson Corr. | Significance | |

| Involvement | .151 | <.001 |

| Smartphone willingness to pay | .147 | <.001 |

| Attachment | .090 | .014 |

Table 5: Correlation between involvement and attachment with repair attempts

Source: Authors

As the table shows, there is a significant but weak correlation between attachment and the number of repair attempts. The cross-check with involvement and willingness to pay provides highly significant correlations in the expected direction, which are slightly higher in terms of value than for the attachment measured.

In summary, significant correlations between attachment and PEB in relation to the smartphone can be identified. However, these are rather weak and, above all, they are heterogeneous: higher attachment is associated with a shorter period of use, but a higher number of repair attempts. A consistent effect of attachment in the direction of PEB cannot be identified for the smartphone.

Hypothesis two postulated a negative relationship between EBBT and PEB. In line with the hypothesis, we find a significant correlation between EBBT and smartphone usage time (r =-.163, p<.001). In contrast, there is a positive correlation with the number of repair attempts (r= .129, p<.001). So while EBBT counteracts PEB when looking at service life, EBBT tends to be environmentally beneficial when it comes to possible repair attempts.

Hypotheses 3.1 and 3.2 concern the intentions for future use of the smartphone. The future intentions of consumers have already been reported descriptively above (3.3.2): In line with H3.1, there is a clear tendency towards practicing PEB in the future by extending usage. Additional open responses validate this finding.

In contrast, the correlation postulated in H3.2 cannot be found empirically. The index of the future intention to purchase a new device more frequently (values between 0 and 4, see above) has a significant but low correlation with the previous duration of use (Spearman rho = -0.77, p=.035). A comparison of mean values shows that, overall, people who have replaced their smartphone slightly more frequently to date still intend to change it slightly more frequently than people who have used it for longer.

This shows that in the case of smartphones, public pressure to demonstrate a PEB by using them for a longer period of time does not yet have a behavior-determining influence compared to previous habits and other influencing factors of consumer behavior.

H 4.1 and H 4.2 postulated a negative correlation between psychological obsolescence and usage behavior. For validation purposes, we also consider the findings on functional obsolescence. As Table 6 shows, psychological obsolescence is associated with a lower service life, in line with the hypothesis. An additional multiple regression analysis confirms what was already indicated in the correlations: functional obsolescence has an even stronger influence (beta = .157) on service life than psychological obsolescence (beta = .124); both factors are highly significant (p<.001).

With regard to the future trend of the PEB, functional obsolescence has no measurable influence: whether the smartphone is replaced in the event of technical problems will not be decided differently in the future than in the present. However, in line with H4.2, there is a significant correlation with psychological obsolescence. If psychological obsolescence is perceived, then this will also be a reason for consumers to change their device more frequently in the future. It therefore works against the logic of a PEB in both the current and intended future behavior of consumers if the planned service life is considered as a criterion.

The opposite result is obtained if the number of repair attempts is used as a criterion for PEB. Both psychological (r= .136, p<.001) and functional obsolescence (r= .138, p<.001) are positively correlated with the number of repair attempts made and thus a PEB. It can be seen that the various behaviors to be understood as PEB are practiced differently depending on influencing factors.

| 2.3 Current useful life | [9] Index future trend useful life (change frequency) | |||

| Pearson-Corr. | Sig. (2-tailed) | Spearman-Rho | Sig. (2-tailed) | |

| Functional obsolescence | -.255 | <.001 | .025 | .495 |

| Psychological obsolescence | -.176 | <.001 | .177 | <.001 |

| Voluntary self-restraint in consumption | ,301 | <.001 | .123 | <.001 |

Table 6: Current and future use of smartphones in the context of obsolescence and voluntary self-restraint in consumption

Source: Authors

H 5.1 and H 5.2 postulated a positive correlation between voluntary self-restraint in consumption and usage behavior.

Table 6 shows that both hypotheses are supported. Self-restraint is already associated with a highly significant longer period of use today and also with extending this in the future.

3.3.8 Comprehensive analysis

Descriptive analyses and the examination of the individual hypotheses yield differentiated

results; in many cases, the constructs prove to be less explanatory, and in some cases even inversely related to the dependent behavioral variables than postulated. With regard to the PEB (useful life, repair attempts), the consumers show differentiated actions; by no means is there a consistent environmentally oriented behavior.

Beyond separate analyses, it remains to be clarified how the various constructs interact with the PEB. Related hypothesized constructs such as Attachment and Involvement as well as potentially antagonistic ones (self-restraint versus EBBT) are subject to the problem of multicollinearity. We therefore subjected the five main independent variables of our study to a new dimensionality check. The principal component analysis solves the problem of multicollinearity with the default setting „orthogonal rotation“.

Here, a three-factor solution, which represents a total of 77.4 percent of the variance, provides clear and easily interpretable factor assignments of the items that correspond to the required simple structure.

| Rotated component matrix | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Component | |||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| Involvement (7) | .816 | .193 | .176 |

| Attachment (means 11.1, 11.2, 11.3, 11.4, 11.5, 11.7) | .878 | .031 | .118 |

| Psychological obsolescence (factor score) | .215 | .073 | .936 |

| Exploratory buying behavior (means 12.1, 12.4) | .092 | .871 | -.111 |

| Self-restraint in purchasing behavior (12.2) | .121 | .721 | .331 |

Extraction method: Principal component analysis. Rotation method: Varimax with Kaiser-normalization. Rotation converged in 4 iterations.

Table 7: Factor loadings of relevant constructs

Source: Authors

As the table shows, involvement and attachment form a common factor. A suitable term for a common dimension of consumer behavior that encompasses both involvement and attachment could be „emotional connection.“ This phrase reflects the emotional engagement (attachment) consumers feel towards a product, brand, or service, along with their active participation and interest (involvement) in the consumption experience.

EBBT and self-restraint in purchasing behavior also form a factor. The dimension of consumer behavior addressed here obviously has two poles. EBBT expresses a potential propensity to consume, while self-restraint implies the opposite. How this dimension is named therefore depends exclusively on the perspective (pro EBBT corresponds to contra self-restraint and vice versa). Our proposal for the wording is based on the fact that EBBT has the somewhat greater factor loading, so we call this dimension exploration-driven consumerism (EDC).

In the final overall analysis, in addition to the emotional connection and the EDC, we included psychological obsolescence, age as a key socio-demographic criterion (see above) and consumers’ willingness to pay, which is also a key determinant of purchasing behavior for a high-quality consumer good. We examined these for their connection with PEB.

| Dependend: | Dependend: | Dependend: | Dependend: | |||

| Current useful life | Current useful life | Current useful life | Total number of repair attempts | Total number of repair attempts | Total number of repair attempts | |

| Standard. coefficient Beta | T | Sig. | Standard. coefficient Beta | T | Sig. | |

| Emotional connection | -.242 | -7.291 | <.001 | .036 | .958 | .338 |

| Exploration-driven consumerism | -.143 | -4.348 | <.001 | .050 | 1.344 | .179 |

| Psychological obsolescence | -.231 | -7.154 | <.001 | .116 | 3.191 | .001 |

| [13] Age | .284 | 8.084 | <.001 | -.210 | -5.325 | <.001 |

| [5] Willingness to pay | .034 | .988 | .324 | .043 | 1.110 | .267 |

Table 8: Standardized coefficients of multiple regression analysis

Source: Authors

Table 8 shows that emotional connection, EDC and psychological obsolescence each correlate negatively with smartphone usage time. Among these three independents, emotional connection is relatively the most significant, closely followed by psychological obsolescence, while EDC has slightly less influence. Age leads to prolonged device use; of all the independents, this is the most significant determinant of PEB.

It is noteworthy that the price, which is weakly related to the useful life when considered on its own (the greater the willingness to pay, the shorter the useful life, r=-.179, p<.001), appears to have practically no significance for the PEB when considered in conjunction with the other independent variables. The few variables included here together explain a relevant part of the period of use (R=.524, R2=.275), although this also depends on a large number of other variables not controlled for here (contract durations, technological innovation, business vs. private use, etc.).

The finding regarding the relative insignificance of price is reiterated when considering the number of repair attempts as the dependent variable. With regard to age, the result is reversed: repair attempts are made more frequently by younger people. Among the psychographic constructs, only psychological obsolescence is significantly related to the number of repair attempts.

4 Discussion and future research opportunities

Based on the TPB, we pursue an approach that considers psychographic constructs to be particularly relevant, which can be expected to be as directly related to behavior as possible, i.e. less general ideas about what is desirable, but rather EBBT, for example. With regard to behavior, we suggest looking at specific, object-related behavior („How long do you use your smartphone before you buy a new one?“) rather than general behavior („I behave in an environmentally friendly way.“).

Our study chose antagonistic factors to approximate how opposing personality and product traits influence pro-environmental behavior. Intriguingly, our results do not point in a clear direction, as factors ambiguously predicted both initiatives to repair (as a pro-environmental behavior) and decreased service lives of smartphones (as a non-environmental behavior). Furthermore, as both functional and psychological obsolescence influenced new purchases and repairs, our results suggest an interplay between a smartphone’s functionality and a consumer’s identity. This perspective allows us to draw some theoretical implications for sustainable behavior.

First, smartphones are high involvement products since they are necessary for a wide variety of purposes in contemporary western societies. Unsurprisingly, this constitutes a need for functionality, resulting in replacements once, for instance, the battery life is depleted, or other technical dysfunctionalities occur. However, despite this high involvement, people do not increase service lives despite attachment. Rather, exciting possibilities such as the potential to fully repair technology predict the proliferation of smartphone usage through exploratory buying behavior tendencies as a mediator. This implies that not pro-environmental tendencies and norms, but feasible applications in turn result in more sustainable behavior. As Germany has comparatively widespread legislation for repairing products (which in turn might broaden possibilities to repair), our results imply that legislative efforts to allow for reparations might in turn increase sustainable behavior independent from personal norms. This has numerous implications for the role of consumers, organizations, and governments regarding sustainable transformations, which should be investigated in further research. Our efforts also highlight a need to broaden our understanding of the attitude-intention-behavior gap to not only include intentions for sustainability, but more product-related factors as well. In general, our finding that consumers do not act consistently with regard to the PEB must be taken into account. Different dependent variables (duration of use versus repair attempts) lead to divergent correlations with psychographic constructs.

Second, our results highlight the role of age throughout consumption behavior. While this understanding is not new at all, it calls into question whether younger consumers indeed increasingly value sustainability. A younger age consistently and significantly predicted shorter service lives more impactful than socioeconomic characteristics (e.g., migration, place of residence, education). On the one hand, this points to the role of smartphones as a status good for younger people, represented by a need for having a new and functional smartphone. On the other hand, from a market perspective, this highlights how decreased periods between rollouts of new products can actively counteract sustainable consumer behavior. Notably, even the price did not significantly impact the service life of a smartphone except for increased initiatives to repair faulty parts, which, however, might be explained by less technological knowledge from older users.

Third, the overlap of constructs might imply two novel dimensions. Attachment and involvement can be grouped into emotional connection. This phrase reflects the emotional engagement (attachment) consumers feel towards a product, brand, or service, along with their active participation and interest (involvement) in the consumption experience. Emotional connection thus suggests a holistic view of the emotional and active aspects of consumers’ connections with the consumption experience, which can promote (e.g., when reparations are part of this experience) or prevent (e.g., when functionality is negatively impacted) sustainable behavior.

Following the previous conceptualization, we see emotional connection as a typical construct where the self is prioritized over the environment (Martenson 2018; Elhaffar et al. 2020).

Secondly, exploratory buying behavior and self-restraint represent two polar-opposite extremes of the same phenomenon. We coin this continuum exploration-driven consumerism, which evaluates the degree to which individuals actively seek novel and diverse products or experiences, often without considering sustainable buying and usage behavior. It reflects a consumer approach where the excitement of exploration tends to outweigh thoughtful spending practices, leading to a prevailing pattern of unrestrained and spontaneous purchases. While we see potential to use such exploration-driven consumerism for sustainability (by incentivizing the more sustainable product alternative), more frequent consumption is not pro-environmental behavior per se, highlighting the sustainability-prevention mechanism of exploration-driven consumerism. Depending on specific behavior within the continuum (e.g., personal initiatives to repair as an exploration-driven consumerism), this concept can either be categorized as prioritizing the self, or as a typical intrapsychic conflict (Elhaffar et al. 2020). Future research could separate both cases.

5 Limitations

Our study neither intends to contradict existing research approaches nor to modify the TPB or other models. The model presented above only describes the main sub-constructs we have included; it makes no claim to completeness or general validity; in particular, we have not controlled for the large number of possible interaction effects. All results relate to the social environment in Germany at the time of the survey. They relate exclusively to the smartphone as the object of the study, i.e. a consumer good that is associated with a particularly high level of involvement for large sections of the population. High awareness of an important gadget implies increased reflection on its assessment and use and an above-average ability to provide information.

For the purpose of a smooth and not overly long survey, we have drastically reduced the scales of the included constructs compared to the original questionnaires. Critics may object that the validated complete original scales could lead to more differentiated and more reliable results. We do not oppose this, but point out that the shortened scales used lead to highly significant contributions to the explanation of variance of the dependent variables in practically all cases and thus fulfilled the purpose of the present study.

Whether the dimensions emotional connection and exploration-driven consumerism that we found provide reliable psychographic constructs must be examined in further research. Throughout the study, we have positioned pro-environmental behavior as congruent to sustainable behavior. We acknowledge that recent conceptualizations of sustainability expand the concept beyond a pure environmental focus. As we used service life and repair attempts as a proxy for sustainable consumption behavior, pro-environmental behavior seemed the most appropriate. We, however, call for more research appropriating an enriched concept of sustainable behavior.

Literatúra/List of References

- Adrion, M. and Woidasky, J., 2019. Planned obsolescence in portable computers – empirical research results. In: Pehlken, A., Kalverkamp, M., Wittstock, R. (Eds.), 2019. Cascade use in technologies. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Vieweg, 2019. ISBN 978-3-662-57886-5.

- Ajzen, I., 1988. Attitudes, personality, and behavior. Chicago: Dorsey Press, 1988. ISBN 0-335-15854-4.

- Ajzen, I., 1991. The theory of planned behavior. In: Organizational Behavior and Human decision Processes. 1991, 50(2), 179-211. ISSN 0749-5978.

- Ajzen, I., 2020. The theory of planned behavior: Frequently asked questions. In: Human Behavior & Emerging Technologies. 2020, 2(4), 1-11. ISSN 2578-1863.

- Baumgartner, H., 2002. Toward a personology of the consumer. In: Journal of Consumer Research. 2002, 29(2), 286-292. ISSN 0093-5301.

- Becher, S. and Sibony, A. L., 2021. Confronting product obsolescence. In: Columbia Journal of European Law. 2021, 27(2), 97-150. ISSN 1076-6715.

- Amelang, M. and Schmidt-Atzert, L., 2006. Psychologische Diagnostik und Intervention. Heidelberg: Springer, 2006. ISBN 978-3-540-28507-6.

- Baumgartner, H. and Steenkamp, J. B. E. M., 1996. Exploratory consumer buying behavior: Conceptualization and measurement. In: International Journal of Research in Marketing. 1996, 13, 121-137. ISSN 1873-8001.

- Becher, S. I. and Sibony, A. L., 2021. Confronting product obsolescence. In: Columbia Journal of European Law. 2021, 97. ISSN 1076-6715.

- Bühner, M., 2011. Einführung in die Test- und Fragebogenkonstruktion. München: Pearson, 2011. ISBN 9783868940336.

- Conner, M. and Norman, P., 2022. Understanding the intention-behavior gap: The role of intention strength. In: Frontiers in psychology. 2022, 13, 923464. ISSN 1664-1078. Available at: <https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.923464>

- Cooper, T., 2004. Inadequate life? Evidence of consumer attitudes to product obsolescence. In: Journal of Consumer Policy. 2004, 27(4), 421-449. ISSN 0168-7034.

- Chyung, S. Y., Swanson, I., Roberts, K. and Hankinson, A., 2018. Evidence-based survey design: The use of continuous rating scales in surveys. In: Performance Improvement. 2018, 57(5), 38-48. ISSN 1090-8811.

- De Canio, F., Martinelli, E. and Endrighi, E., 2021. Enhancing consumers’ pro-environmental purchase intentions: the moderating role of environmental concern. In: International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management. 2021, 49/9, 1312-1329. ISSN 1758-6690.

- DiMatteo, L. A. and Wrbka, S., 2019. Planned obsolescence and consumer protection. The unregulated extended warranty and service contract industry. In: Cornell Journal of Law and Public Policy. 2019, 28, 483. ISSN 1069-0565.

- ElHaffar, G., Durif, F. and Dubé, L., 2020. Towards closing the attitude-intention-behavior gap in green consumption: A narrative review of the literature and an overview of future research directions. In: Journal of cleaner production. 2020, 275(4), 122556. ISSN 0959-6526.

- Escalas, J. E., 2004. Narrative processing: Building consumer connections to brands. In: Journal of Consumer Psychology. 2004, 14(1-2), 168-180. ISSN 1057-7408.

- Fuchs, D., Sahakian, M., Gumbert, T., Di Giulio, A., Maniates, M., Lorek, S. and Graf, A., 2021. Consumption corridors. Living a good life within sustainable limits. London, New York: Routledge, 2021. ISBN 9780367748746.

- Graves, C. and Roelich, K., 2021. Psychological barriers to pro-environmental behaviour change. In: Sustainability. 2021, 13(21), 11582. ISSN 2071-1050.

- Grout, P. and Park, In-Uck, 2005. Competitive planned obsolescence, In: RAND Journal of Economics. 2005, 36(3), 596-612. ISSN 0741-6261.

- Hardeman, M., Johnston, M., Johnston D., Bonetti, D., Wareham, N. and Kinmonth, A. N., 2002. Application of the theory of planned behaviour in behaviour change interventions: A systematic review. In: Psychology & Health. 2002, 17/2, 123-158. ISSN 1476-8321.

- Heeren, A. J., Singh, A. S., Zwickle, A., Koontz, T. M., Slagle, K. M. and McCreery, A. C., 2016. Is sustainability knowledge half the battle? An examination of sustainability knowledge, attitudes, norms, and efficacy to understand sustainable behaviours. In: International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education. 2016, 17 (5), 613-632. ISSN 1758-6739.

- Howard, J. A. and Sheth, J. N., 1969. The theory of buyer behavior. New York: John Wiley, 1969.

- Kuppelwieser, V. G., Klaus, P., Manthiou, A. and Boujena, O., 2019. Consumer responses to planned obsolescence. In: Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services. 2019, 47 (C), 157-165. ISSN 1873-1384.

- Laaksonen, P., 1994. Consumer involvement, concepts and research. London: Routledge, 1994. ISBN 9780415097604.

- Laitala, K., Grimstad Klepp, I., Haugrønning, V., Throne-Holst, H. and Strandbakken, P., 2021. Increasing repair of household appliances, mobile phones and clothing: Experiences from consumers and the repair industry. In: Journal of Cleaner Production. 2021, 282(2), 125349. ISSN 1879-1786.

- Lewis, J. R. and Erding, O., 2017. User experience rating scales with 7, 11, or 101 points: Does it matter? In: Journal of user experience. 2017, 12(2), 73-91. ISSN

3065-7504. - Leung, S. O., 2011. A comparison of psychometric properties and normality in 4-, 5-, 6-, and 11-point Likert scales. In: Journal of Social Service Research. 2011, 37(4), 412-421. ISSN 1540-7314.

- Li, D., Zhao, L., Ma, S., Shao, S. and Zhang, L., 2019. What influences an individual’s proenvironmental behavior? A literature review. In: Resources, Conservation and Recycling. 2019, 146, 28-34. ISSN 1879-0658.

- Machová, R. and Zsigmond, T., 2022. Planned obsolescence with the eyes of university students. In: The Poprad Economic and Management Forum. 2022, 392. ISBN 978-80-561-0995-3.

- Martenson, R., 2018. When is green a purchase motive? Different answers from different selves. In: International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management. 2018, 46(1), 21-33. ISSN 1758-6690.

- Nguyen, H. V., Nguyen, C. H. and Hoang, T. T. B., 2019. Green consumption: Closing the intention‐behavior gap. In: Sustainable Development. 2019, 27(1), 118-129. ISSN 1099-1719.

- Packard, V., 1960. The waste makers. London: Longmans, 1960.

- Pantano, E., Iazzolino, G. and Migliano, G., 2013. Obsolescence risk in advanced technologies for retailing: A management perspective. In: Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services. 2013, 20(2), 225-233. ISSN 0969-6989.

- Riedl, J., Wengler, S., Czaban, M. and Steudtel, S., 2023. Sexism in advertisements – a cross-cultural analysis. In: Marketing Science & Inspirations. 2023, 1(3), 2-16. ISSN 1338-7944.

- Riedl, J. and Zips, S., 2015. Positionierungsmodell für Marken. In: Planung & Analyse. 2015, 2, 38-42. ISSN 0724-9632.

- Santor, D. A., Fethi, I. and McIntee, S. E., 2020. Restricting our consumption of material goods: An application of the theory of planned behavior. In: Sustainability. 2020, 12, 800. ISSN 2071-1050.

- Satyro, W. C., Sacomano, J. B., Contador, J. C. and Telles, R., 2018. Planned obsolescence or planned resource depletion? A sustainable approach. In: Journal of Cleaner Production. 2018, 195, 744-752. ISSN 0959-6526.

- Schifferstein, H. N. J. and Zwartkruis-Pelgrim, E. P. H., 2008. Consumer-product attachment: Measurement and design implications. In: International Journal of Design. 2008, 2(3), 1-13. ISSN 1991-3761.

- Sheeran, P. and Webb, Th. L., 2016. The intention-behavior gap. In: Social and Personality Psychology Compass. 2016, 10(9), 503-518. ISSN 1751-9004.

- Stankuniene, G., Streimikiene, D. and Kyriakopoulos, G., 2020. Systematic literature review on behavioral barriers of climate change mitigation in households. Sustainability, 12(18), 7369. ISSN 2071-1050.

- Sutton, S., 1994. The past predicts the future: Interpreting behaviour-behaviour relationships in social psychological models of health behaviour. In: D. R. Rutter and L. Quine (Eds.), 1994. Social psychology and health: European perspectives Avebury: Ashgate Publishing Co., 1994, 71-88. ISBN 978-1856285629.

- Olson, J. A., Sandra, D. A., Colucci, É. S., Al Bikaii, A., Chmoulevitch, D., Nahas, J. and Veissière, S. P., 2022. Smartphone addiction is increasing across the world: A meta-analysis of 24 countries. In: Computers in Human Behavior. 2022, 129, 107138. ISSN 1873-7692.

- Park, H. J. and Lin, L. M., 2020. Exploring attitude-behavior gap in sustainable consumption: Comparison of recycled and upcycled fashion products. In: Journal of business research. 2020, 117, 623-628. ISSN 1873-7978.

- United Nations General Assembly, 2015. Resolution adopted by the General Assembly on 11 September 2015. New York: United Nations. 2015. [online]. [cit. 2024-02-10]. Available at: <https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/migration/generalassembly/docs/globalcompact/A_RES_70_1_E.pdf>

- Utaka, A., 2006. Planned obsolescence and social welfare. In: The Journal of Business. 2006, 79(1), 137-148. ISSN 0021-9398.

- Weitensfelder, L., Heesch, K., Arnold, E., Schwarz, M., Lemmerer, K. and Hutter, H.-P., 2023. Areas of individual consumption reduction: A focus on implemented restrictions and willingness for further cut-backs. In: Sustainability. 2023, 15, 4956. ISSN 2071-1050.

- Yuriev, A., Dahmen, M., Paillé, P., Boiral, O. and Guillaumie, L., 2020. Pro-environmental behaviors through the lens of the theory of planned behavior: A scoping review. In: Resources, Conservation & Recycling. 2020, 155, 104660. ISSN 1879-0658.

- Zaichkowski, J. L., 1985. Measuring the involvement construct. In: The Journal of Consumer Research. 1985, 12(3), 341-352. ISSN 1537-5277.

Kľúčové slová/Key words

consumer behavior, pro-environmental behavior, sustainable consumption, sustainable development goals

spotrebiteľské správanie, proenvironmentálne správanie, udržateľná spotreba, ciele udržateľného rozvoja

JEL klasifikácia/JEL Classification

M31

Résumé

Hypotetické konštrukcie spotrebiteľského správania ako prediktory proenvironmentálneho správania. Empirická štúdia založená na smartfónoch.

Napriek tomu, že ide o špecifický cieľ udržateľného rozvoja (SDG), úloha spotrebiteľov v oblasti udržateľnej spotreby je stále nejednoznačná. Príkladom toho je obrovské množstvo výskumov o rozdiele medzi postojmi, zámermi a správaním, ktoré vo všeobecnosti opisujú zlyhania spotrebiteľov pri správaní sa udržateľne, ako sa teoreticky predpokladá. Nedávne recenzie podnietili ďalšie skúmanie nad rámec existujúcej literatúry o faktoroch ovplyvňujúcich túto medzeru. K tejto výzve prispievame kvantitatívnym skúmaním piatich antagonistických dimenzií – intrapsychických aj situačných – používania smartfónov a udržateľného správania spotrebiteľov v Nemecku (n=800). Naše výsledky poukazujú na dva nové koncepty. Emocionálne prepojenie – t. j. spojenie spotrebiteľov so skúsenosťami so spotrebou – môže buď podporovať, alebo predchádzať udržateľnému správaniu, zatiaľ čo prieskumné správanie spotrebiteľa – t. j. nové nákupy v dôsledku exploatačných tendencií – zvyčajne oslabuje udržateľné správanie. To ilustruje, ako a kedy udržateľnosť prevažuje nad inými spotrebiteľskými postojmi. Tieto výsledky uvádzame do kontextu a v závere našej štúdie poukazujeme na obmedzenia a možnosti ďalšieho výskumu.

Recenzované/Reviewed

16. March 2024 / 29. March 2024