1 Introduction and context

A memorable educational experience does not happen by chance. It is thoroughly designed. Designing an educational experience, be it a university program or major, a course, a module, or even a lecture, can benefit from a systematic approach. This article will present the design of an international marketing course using learning experience design principles (Floor 2023) and principles of instructional design (Parrish, Wilson, Dunlap 2011). The approach is based on experimental learning theory (Kolb and Kolb 2005; Jarvis 2012) that favors educational formats with real-life engagement (Purcell, Pearl and Van Schyndel 2021). We advocate a shift in the overarching assumption about learners from pedagogy to andragogy (McNally et al. 2020), leading to a transition from a teacher-centered to a learner-centered educational approach (Knowles 2005; Smart, Witt and Scott 2012). Finally, the course uses a diverse student population as an asset (Pineda and Mishra 2023), aiming to develop their intercultural competence (Guillén-Yparrea and Ramírez-Montoya 2023) as a transversal learning outcome (Sá and Serpa 2018).

The article discusses a course design, addresses some aspects of course quality, and responds to a literature discussion that points out that the dominant focus in higher education is on research output and quality (Harrison et al. 2022), despite the fact that education and teaching are recognized as equally important and relevant.

The aim of the article is to provide a theoretical and practical framework for the systematic design (or re-design) of an international marketing course. The universality of applied principles goes beyond and can be instrumental to (re)designing courses in business administration or any other field. In the theoretical anchoring, we will present a tool for the systematic design of a learning experience, followed by a brief elaboration of the educational principles supporting it. The presented course can serve as an inspiration or a starting point for peers facing similar challenges. At the end, we will reflect on the effectiveness of this approach.

The course could be described as an international marketing course based on real-client projects (Kokotsaki, Menzies and Wiggins 2016), where a small group of culturally diverse students is assigned to support the internationalization journey of a local SME. The work on the project enables problem based (Savery 2015; Gallagher and Savage 2023) and collaborative learning (Smith and McGregor 1992), where students are integrated into the real work environment and gain knowledge and skills in international marketing while performing community service (Bandy 2016). Furthermore, this type of course, based on the local context and student experience, can address some of the challenges reported by Jafari and Keykha (2024) in misusing AI in the course assessment.

2 Theoretical anchoring

Based on understanding how a person learns, an educator will develop activities to support learning but also define the result of the learning process (Kay and Kibble 2016). Following the idea of marketing as a managerial discipline and the call for the increased relevance of marketing education for practice (Fehrer 2020; Hughes et al. 2012), we are inclined to adopt the experiential learning theory that will guide the design of the course.

According to Jarvis (2012), the result of learning is personal transformation into a more experienced person. In our case, the experience is an input or learning method, as students are assigned to work with local SMEs throughout the duration of the course. At the same time, experience is an outcome, as a student finishes the course as a more experienced person.

2.1 Designing the learning experience

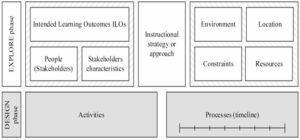

Following the idea of experiential learning, a fitting and comprehensive tool can be Learning Experience Canvas or LX Canvas (Floor 2023). LX Canvas supports the design process, and it is based on the approach that everything we learn, we learn from experience. The tool can be divided into two significant perspectives or phases: (1) explore-gaining insights into people, context, and strategies; and (2) design-translating strategy into actionable activities and processes leading to desired learning results. We use a slightly modified version of the original LX canvas (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Modified learning experience canvas

Source: Adapted from Floor (2023, p. 148-149)

2.1.1 Explore: Insights and analysis

LX Canvas has a quality of user-centered-design and starts with what a learner needs to learn, which translates to intended-learning-outcomes (ILOs). In the context of the course (or program), the defined ILOs will materialize in the course activities and content, specifying the way the learning will be delivered (the course process), and finally connecting with the assessment (Greensted and Hommel 2014).

The tool further suggests knowing the stakeholders (all parties having an interest in the process and outcomes of learning experience) and focusing on learners – by collecting as much information as possible about them, which is useful for the design phase.

The ILOs and stakeholders are placed in the context: location where learning is to happen (campus and/or off-campus setting, virtual or physical, availability and access to different locations), as well as resources and constraints that must be considered. Last, but not least, Floor (2023) writes about environment – through the lenses of how the (physical) aspects of location enable interaction among participants in the learning process and facilitate learning as a societal and collaborative process. This resembles the idea of „learning spaces“ by Kolb and Kolb (2005, p. 200), interpreted „not necessarily as physical places but as constructs of the person’s experience in the social environment.“

A deep understanding of the stakeholders and the context where learning is to happen (including resources and constraints) is processed into an instructional strategy. An overarching decision on the way to deliver experience: using teacher-centered or learner-centered approach; pedagogical or andragogical approach; theoretical anchoring of learning (e.g., experiential approach to learning or cognitive); individual or collaborative learning; or their combination.

The purpose of deliberating about instructional strategy is to have time to re-think your approach to the course delivery, allowing you to explore other options beyond stereotypical solutions. I.e., one can teach about internationalization motives by lecturing and referring to a textbook or journal article; the next option might be using a case study, but you might also connect students with local businesses and make them investigate different internationalization motives working within a company project. In each of these scenarios, the roles of teacher and learner will be different, as well as the expectations. The strategy part is about being open-minded and recognizing different routes to reaching the intended learning outcomes.

2.1.2 Design: Activities and processes

The instructional strategy will be a base for deciding the activities and their sequence. Being on the position of experiential learning, we design a participatory learning experience where learners (students) can apply and test theoretical knowledge working with real organizations on the issues and assignments typical for their future roles in organizations. According to Forrest and Peterson (2006, p. 118), „experience becomes a textbook,“ which facilitates transforming theory into understanding (Chan 2012).

We transition from pedagogy (in a narrower context, the science and practice of teaching children) to andragogy (where the focus is on adult learners). McNally et al. (2020) argue that the pedagogical approach does not tailor to the needs of the Millennial students we meet on campus nowadays: they are more independent (Jones, Penaluna, and Penaluna 2019), internally motivated and driven by the relevancy of the education they receive, engaged when learning is problem-based, and their voice is acknowledged, making them active participants in their education.

3 A practical application: an international marketing course

Learning experience Canvas provides us with the structure, checklist, or planning tool that helps to, in a methodical way, design and deliver a learning experience. It starts with knowing your learner (understanding the audience(s)) and a meticulous inventory of the learning outcomes we want learners to acquire (referred to as ILOs). In the next step, we analyze the available resources and constraints we face, understanding where the learning happens, not just as a physical space but also as a facilitated interaction between participants. These two perspectives merge to find a desirable (suitable) instructional strategy, which boils down to one question: what kind of educator do we want to be and what is our educational approach? Lastly, consistent with the strategy, an educator needs to operationalize the learning experience by designing activities and creating a coherent sequence leading to fulfillment of ILOs. The course was built on these principles, and we will use them to demonstrate practical application.

3.1 Explore: ILOs and stakeholders

The course is placed in the context of a business school in southern Sweden, and it is part of the curriculum of three master-level programs: International marketing, Strategic entrepreneurship, and Global marketing management. It is equivalent to 7.5 ECTS credits and delivered in a 10-week time frame during the spring semester. There are several stakeholders in the course: students (learners), local SMEs, the local community (in a broad sense, but also in a narrower sense, represented by governmental organizations supporting SMEs), and finally the business school.

The course is at its core – an international marketing course; therefore, from a disciplinary perspective, it will have a recognizable structure of intended learning outcomes (see Table 1). The distinctive feature of the course is the application of international marketing, learning by doing, and applying theory in a real-life context. This allows students to apply and test theoretical concepts, making them more relevant and memorable since they have been learned in the real-life setting.

| Category | Specific ILOs in context of international marketing |

|---|---|

| Knowledge and understanding | 1. Describe and explain the internationalization process |

| 2. Describe internationalization theories and motives | |

| 3. Outline marketing intelligence/ research process | |

| 4. Explain foreign market selection and modes of entry | |

| 5. Explain the specifics of instruments of the marketing mix | |

| Skills | 6. Carry out a systematic assessment of a foreign market |

| 7. Argue for decisions made in international marketing planning, strategy, and execution | |

| 8. Formulate and design internationalization effort of a company by providing research, strategies, and tactical suggestions | |

| Judgement and approach | 9. Reflect on the intercultural experience with the purpose of developing intercultural competence |

Table 1: Intended learning outcomes (ILOs) in the AIM course

Source: author

On average, there are around 60 students in the course; the student population is quite diverse, and there are more than fifteen nationalities in the average intake, where over 75% of students are foreign students. Explaining the value of experience and personal gains of working with real-life clients in the course projects is of outmost importance (Makani and Rajan 2016), so the course is pitched a month before the first lecture to the students. The students take an entry survey in which we collect data on nationality, languages spoken, work, education and life relevant experiences, and interest in working with specific markets, industries, products/services, etc. Furthermore, the data is complemented with the academic performance. This information is used for creating project groups but also as an important input in fine-tuning the course content and delivery.

The course will host a matching number of SMEs for student projects. We work together with them in creating project assignments that reflect the course ILOs but also the interests of the companies. The Swedish SMEs are incentivized to export, but as SMEs everywhere, they have limited resources, limited knowledge about foreign market opportunities, and have a hard time accessing information across the language barrier (Tillväxtverket 2018; Mort and Weerawardena 2006; Elenurm 2008; Zahra et al. 2009; Danford 2006).

Collaborative activities with academia are beneficial for companies’ business performance (Goel et al. 2017), and Heriot et al. (2008) use the term academic consulting to describe services that students provide to local companies. Participating SMEs frequently fit into the network theory of internationalization (Che Senik et al. 2011), where success comes from the capacity to gain knowledge from external resources through collaborations, including one with universities or business schools. The collaborative approach is also typical for international entrepreneurship (Hagen, Denicolai and Zucchella 2014). Our diverse student population is assigned as temporary resources to local SMEs and helps them reduce the cost of foreignness. At the same time, students learn international marketing by „walking the talk,“ applying and testing in practice what they learned in textbooks and school.

Given that students perform significant service for the community, by supporting Swedish exporters, which in turn generates prosperity for society, we were able to attract partners to support the course by helping recruit companies, participating in guest lectures, grading project presentations, and even awarding the best three students presentations with symbolic monetary prizes. The course has a long-standing cooperation with several governmental organizations supporting Swedish exporters, known as Team Sweden: ALMI (Business Development Agency), Business Sweden, the Swedish Export Credit Agency (EKN), Enterprise Europe Network (EEN), and the Swedish Export Credit Corporation (SEK).

Finally, the course is an exemplary course to demonstrate dedication to the third mission and embeddedness of the business school in the community. It serves as a signal about a relevant, contemporary, and engaging approach to education for the next generation of business leaders.

3.2 Explore: Situational factors

Situational factors are about location, environment, resources, and constraints, and as such will be heavily dependent on the availability and access in each context. For the design of the course (or experience), we will share a couple points that can make a difference.

Location refers to places where the learning happens. We should always use the best possible place or venue that facilitates learning. E.g., for some course moments we use a flexible teaching space (Mononen, Havu-Nuutinen and Haring 2023), where the furniture can be arranged in different ways, with the aim to foster interaction among the participants. This space is also used for joint project kick-offs where we invite both students and participating companies, as well as for lectures that introduce students to working in multicultural teams.

If the goal is to convey information and present theoretical background, the more traditional classroom setting will be used. Furthermore, it must be emphasized that learning in this approach, more than in any others, is also to happen in interaction between different participants outside the formal class hours. Learning happens in collaboration between students within a project group but also in interaction with a host company.

Cultural diversity is the single most interesting characteristic of the student group. We approached this as an asset/resource that could be mobilized for the purpose of the projects with SMEs. All other resources (instructors, course materials, time, money) are easier to manage. The compositional diversity of students, at the same time, is the biggest challenge (Popov et al. 2012), and potentially the greatest asset. Creating intercultural groups from people that barely know each other and setting them toward mutual goal can easily become a liability. Intercultural groups need to be trained and managed to collaborate across differences. „…it has been found that these positive effects of intergroup contact are most prominent when intergroup contact takes place in an environment that fosters (a) common goals, (b) equal status, and (c) intergroup cooperation“ (Bocanegra, Markeda and Gubi 2016).

Success of these types of courses is dependent on thorough planning (Berard and Ravellli 2021). Thorough planning needs to manage expectations of all parties involved and, to an extent reasonable, manage interactions and processes. Managing the expectations of host companies and students is pivotal to success. To address uncertainties, clear and open communication is important, as is a set of documents that assure academic outcomes of the course, regulate interactions, and manage the responsibilities of all parties involved in interactions between students and between students and host companies.

Educators running these types of courses must accept the fact that shifting educational focus from campus and classroom to the outside world and multiple interactions of stakeholders without direct participation in all these processes. This means partly giving up control over the course and learning processes. The desired ILOs are achieved by utilizing resources and circumventing constraints by aligning multiple stakeholders’ interests in a set of processes and activities, where constructive alignment between ILOs, course content, interactions, and planned assessments needs to be well executed.

3.3 Designing

In the designing phase, we need to put together different pieces of the course, arrange them in the timeline, and connect them to create a coherent learning experience. According to Brennan (2014), marketing educators need to be aware that experiential learning is not just a simple creation of practical experiences and interactions but rather a complex design that is to secure achievement of educational goals. The course elements must be aligned with ILOs, and ILOs connected with the assessment.

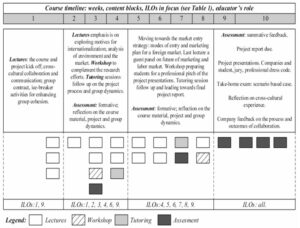

The course encompasses the following activities: lectures, workshops, tutoring sessions, reflections, and the take-home exam. The activities are divided into four blocks, supporting students’ learning experience by combining content with formative and summative feedback, situated both at the group and individual level. Without going into analytical details of presenting the individual activities in the course, we will try to portray the general idea by discussing the course activities in conjunction with the experiential learning process and the roles that, according to Kolb and Kolb (2018), an educator takes to guide learners through the journey (see Figure 2).

If we think about the timeline of the course, the project requires insights and tools at the beginning and more time to concentrate on the project work towards the end of the course. Therefore, the load of lectures in the course is shifted towards the first half of the course, arming students with theoretical anchoring, leaving them more room to craft the project towards the end.

Experiential learning explains learning as a non-linear movement through phases of concrete experience, reflective observation, abstract conceptualization, and active experimentation (Kolb and Kolb 2005). The course design needs to create the learning process that enables learners to go through this process. E.g., if students are to learn about the internationalization motives, the concrete experience could be anything in the range of reading about it in literature, presenting it in the class, or „localizing“ it at the interaction with the company. The concrete experience needs to be processed; therefore, the activities and assessments are put in place to guide the learner towards the remaining phases. Formative feedback, which gives a chance to the learner to improve, is very important (Seel, Lehmann, Blumschein and Podolskiy 2017).

Figure 2: The course design

Source: author

The learning experience canvas is a simple and versatile tool. It teaches us a valuable lesson that learning is more than just content to be conveyed to learners. Taking an extra step to understand the learner (and stakeholders), as well as the surrounding environment of the course, helps us build a course in a systematic fashion with a more holistic picture. How do we know that it makes any difference?

4 Methodology

The quality assessment of the educational process is complex (Chen and Mohamed 2023); furthermore, according to Griffith (2008), there is no agreement about what the concept of quality of education is. Universities engage in multitudes of different activities to measure and enhance learning, and „self-reported data from students about multiple aspects of teaching quality and perceived effectiveness were the most commonly reported.” (Harrison et al. 2022, p. 87). It is not our intention to engage in the debate or solve the open questions of quality assessment in academia; however, we acknowledge that having some measurements is a must.

To argue for the success of this design, we use student course evaluations for the course and compare them with average scores of all courses in the business school on selected dimensions, keeping in mind shortcomings of the course evaluations as expressed in Berk (2013) and Stronge (2018).

In the business school in the case, the course evaluation process is standardized and administered centrally by the university. The course evaluations have 17 close-ended questions that quantify the perceptions of the course quality on a scale from 1 to 7. The remaining three questions are open-ended, where students elaborate on their reflections on the teacher and positive aspects of the course, as well as provide suggestions for course improvements.

5 Discussion and concluding thoughts

Defining and measuring a course’s quality is not an easy task; there is no unanimous agreement on these, and we can argue their multifaceted nature. In order to capture a difference in perceived experience between the (re)designed course and an average course in the business school, we used course evaluations in capturing overall perception of the course as well as some relevant dimensions. The comparison is done for the last three years (where complete data exist) from 2021 to 2023, and in general we can argue that the course in this case performs better than the average course in the business school (see Table 2).

| Your perception of the course as a whole. (evaluated on the scale from 1 to 7) | The case course | The business school average |

|---|---|---|

| 2021 | 6.1 | 5.1 |

| 2022 | 6.2 | 4.9 |

| 2023 | 5.4 | 4.9 |

Table 2: Comparing performance of the case course to the business school average

Source: author

The next three points are relatable to the course learning since they suggest that students feel they learned important aspects of the topic (Table 3) and that the course contributed to their ability to identify and solve problems (Table 4), as well as a strong connection to the real world (Table 5).

| After the course I feel confident that I have learned the most important aspects of the topic. (evaluated on the scale from 1 to 7) | The case course | The business school average |

|---|---|---|

| 2021 | 6.0 | 5.3 |

| 2022 | 6.1 | 5.2 |

| 2023 | 5.6 | 5.3 |

Table 3: Comparing performance of the case course to the business school average

Source: author

Undeniably, contemporary students require novel approaches; they want to be challenged and exposed to practice; moreover, it is expected of them to be work-ready and immediately, with little training, start contributing to the organizational goals. These types of courses can enhance educational outcomes through increased student engagement (Wurdinger, Haar, Hugg and Bezon 2007) and improved motivation (Thomas 2000), the prerequisites for transitioning students from „surface“ to „deep“ learning, according to Biggs (2012).

| The course challenged me to identify and solve problems (evaluated on the scale from 1 to 7) | The case course | The business school average |

|---|---|---|

| 2021 | 6.3 | 5.5 |

| 2022 | 6.5 | 5.4 |

| 2023 | 6.1 | 5.4 |

Table 4: Comparing performance of the case course to the business school average

Source: author

| The course provided opportunities to relate theoretical knowledge to real-world issues (evaluated on the scale from 1 to 7) | The case course | The business school average |

|---|---|---|

| 2021 | 6.6 | 5.6 |

| 2022 | 6.7 | 5.5 |

| 2023 | 6.4 | 5.6 |

Table 5: Comparing performance of the case course to the business school average

Source: author

The lasting learning impact is achieved by designing a learning experience that is transformative, which requires challenge and high involvement (Parrish, Wilson and Dunlap 2011).

Communication (Table 6) and feedback (Table 7) are of the utmost importance to facilitate the understanding of the course goals, timeline, and dynamics. An educator needs to argue the relevance of the chosen approach; students need to be introduced to the idea of working with real clients and the community and the benefits emphasized (Makani and Rajan 2016). This is needed to counteract resistance to inherent ambiguity and the above-average investment of time and effort in these kinds of projects. The andragogical approach also suggests transparency and explaining to the learners not just what they need to learn but, more importantly, why they need to learn (Taylor and Hamdy 2013).

| Course communication worked well; e.g. about assignment, course changes, and goals (evaluated on the scale from 1 to 7) | The case course | The business school average |

|---|---|---|

| 2021 | 6.8 | 5.3 |

| 2022 | 6.7 | 5.2 |

| 2023 | 6.6 | 5.4 |

Table 6: Comparing performance of the case course to the business school average

Source: author

| I received useful feedback on the course assignments (evaluated on the scale from 1 to 7) | The case course | The business school average |

|---|---|---|

| 2021 | 5.9 | 4.6 |

| 2022 | 6.4 | 4.6 |

| 2023 | 5.8 | 4.8 |

Table 7: Comparing performance of the case course to the business school average

Source: author

The value of a student’s experience for their learning and future career can be indirectly measured by the feedback companies leave related to their cooperation with students, encompassing both perceptions of engagement and professionalism (the process) and the usefulness of the student project reports and results (the content) for the companies. On average, most of the participating companies express a willingness to return to the course in the future (see Table 8) – justifying the value of the course for the local business community.

| Year | Total number of participating companies | Repeated participants | Would participate again (based on the exit survey) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2021 | 13 | 3 | 13 |

| 2022 | 21 | 12 | 19 |

| 2023 | 22 | 13 | 18 |

Table 8: Comparing performance of the case course to the business school average

Source: Authors

As an external validation of the education quality, we can report that the business school in this case has two major accreditations for business schools, AACSB and EQUIS, as well as being ranked in the top 100 business schools in The Financial Times European Business School ranking.

To be fair, running this type of course with real clients is not without effort. These types of courses will require more time, energy, and investment from both the educator and the learners (Makani and Rajan 2016). The literature is rich in issues related to campus collaboration with external partners. Differences in priorities, timelines, and understanding of the project outcomes need to be bridged (Purcell, Pearl and Schyndel 2021).

Marketing educators should leave the proverbial ivory towers. As much as theory and research are important, their value is in application; no less significant is our assignment to shape graduates that have knowledge, skills, and experiences relevant for employment. Fulfilling our mission requires us to connect with the world. Not so far in the past, the classroom was isolated from the outside world, and students would walk into the temple of science, and ties with the world were cut out for a duration of lecture. The educators had the luxury of their undivided attention with far fewer distractions than nowadays. In the contemporary classroom, students are never disconnected from the outside world, and educators compete for their attention with the entire world. Maybe this is the message that we need to let the world into the classroom and take advantage of that for the benefit of the learner, educator, university, and community. Making this possible requires a comprehensive and elaborate design of the course based on „mutuality and reciprocity“ (Moore 2014, p. 3), and educators willing to engage with the real world.

Literatúra/List of References

- Bandy, J., 2016. What is service learning or community engagement. Center for Teaching, Vanderbilt University, 2016. [online]. [cit. 2024-04-14]. Available at: <https://cft.vanderbilt.edu/guides-sub-pages/teaching-through-community-engagement/>

- Berard, A. and Ravelli, B., 2021. In their words: What undergraduate sociology students say about community-engaged learning. In: Journal of Applied Social Science. 2021, 15(2), 197-210. ISSN 1937-0245. Available at: <https://doi.org/10.1177/1936724420975460>

- Biggs, J., 2012. What the student does: Teaching for enhanced learning. In: Higher Education Research and Development. 2012, 31(1), 39-55. ISSN 0729-4360. Available at: <https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2012.642839>

- Bocanegra, J. O., Markeda L. N. and Aaron A. G., 2016. Racial/ethnic minority under-graduate psychology majors’ perceptions about school psychology: Implications for minority recruitment. In: Contemporary School Psychology. 2016, 20(3), 270-281. ISSN 2161-1505. Available at: <https://doi.org/10.1007/s40688-016-0086-x>

- Brennan, R., 2014. Reflecting on experiential learning in marketing education. In: The Marketing Review. 2014, 14(1), 97-108(12). ISSN 1472-1384. Available at: <https://doi.org/10.1362/146934714X13948909473266>

- Danford, G. L., 2006. Project-based learning and international business education. In: Journal of Teaching in International Business. 2006, 18(1), 7-25. ISSN 1528-6991. Available at: <https://doi.org/10.1300/J066v18n01_02>

- Elenurm, T., 2008. Applying cross-cultural student teams for supporting international networking of Estonian enterprises. In: Baltic Journal of Management. 2008, 3(2), 145-. ISSN 1746-5273. Available at: <https://doi.org/10.1108/17465260810875488>

- Fehrer, J. A., 2020. Rethinking marketing: Back to purpose. In: AMS Rev. 2020, 10(3-4), 179-84. ISSN 1869-814X. Available at: <https://doi.org/10.1007/s13162-020-00186-5>

- Floor, N., 2023. This is learning experience design: What it is, how it works, and why it matters. New Riders, 2023. ISBN: 9780138206307.

- Forrest, S. P. and Peterson, T. O., 2006. It’s called andragogy. In: Academy of Management Learning and Education. 2006, 5(1), 113-122. ISSN 1944-9585. Available at: <https://doi.org/10.5465/AMLE.2006.20388390>

- Gallagher, S. E. and Savage, T., 2023. Challenge-based learning in higher education: an exploratory literature review. In: Teaching in Higher Education. 2023, 28(6), 1135-1157. ISSN 1470-1294. Available at: <https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2020.1863354>

- Goel, R. K., Goktepe-Hulten, D. and Grimpe, C., 2017. Who instigates university-industry collaborations? University scientists versus firm employees. In: Small Busniss Economics. 2017, 48(3), 503-524. ISSN 1573-0913. Available at: <https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-016-9795-9>

- Greensted, C. and Hommel, U., 2014. Intended learning outcomes: Friend or foe? In: Global focus. 2014, 8(1), 20- . ISSN 2723-4215.

- Griffith, S. A., 2008. A proposed model for assessing quality of education. In: International Review of Education. 2008, 54(1), 99-112. ISSN 1573-0638. Available at: <https://doi.org/10.1007/s11159-007-9072-x>

- Guillén-Yparrea, N. and Ramírez-Montoya, M. S., 2023. Intercultural competencies in higher education:a systematic review from 2016 to 2021. In: Cogent Education. 2023, 10(1). ISSN 2331-186X. Available at: <https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2023.2167360>

- Hagen, B., Denicolai, S. and Zucchella, A., 2014. International entrepreneurship at the crossroads between innovation and internationalization. In: Journal of International Entrepreneurship. 2014, 12(2), 111-114. ISSN 1573-7349. Available at: <https://doi.org/10.1007/s10843-014-0130-8>

- Harrison, R., Meyer, L., Rawstorne, P., Razee, H., Chitkara, U., Mears, S. and Balasooriya, C., 2022. Evaluating and enhancing quality in higher education teaching practice: a meta- review. In: Studies in Higher Education. 2022, 47(1), 80-96. ISSN 1470-174X. Available at: <https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2020.1730315>

- Heriot, K. C., Cook, R., Jones, R. C. and Simpson, L., 2008. The use of student consulting projects as an active learning pedagogy: A case study in a production/operations management course. In: Decision Sciences Journal of Innovative Education. 2008, 6(2), 463-481. ISSN 1540-4609. Available at: <https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4609.2008.00186.x>

- Hughes, T., Bence, D., Grisoni, L., O’Regan, N. and Wornham, D., 2012. Marketing as an applied science: Lessons from other business disciplines. In: European Journal of Marketing. 2012, 46(1/2), 92-111. ISSN 0309-0566. Available at: <https://doi.org/10.1108/03090561211189257>

- Chan, C. K. Y., 2012. Exploring an experiential learning project through Kolb’s Learning Theory using a qualitative research method. In: European Journal of Engineering Education. 2012, 37(4), 405-415. ISSN 1469-5898. Available at: <https://doi.org/10.1080/03043797.2012.706596>

- Che Senik, Z., Scott-Ladd, B., Entrekin, L. and Khairul A. A., 2011. Networking and internationalization of SMEs in emerging economies. In: Journal of International Entrepernurship. 2011, 9, 259-281. ISSN 1573-7349. Available at: <https://doi.org/10.1007/s10843-011-0078-x>

- Chen, L. and Mohamed Mokhtar, M., 2023. Education on quality assurance and assessment in teaching quality of high school instructors. In: Journal of Big Data. 2023, 10(1). ISSN 2196-1115. Available at: <https://doi.org/10.1186/s40537-023-00811-7>

- Jafari, F. and Keykha, A., 2024. Identifying the opportunities and challenges of artificial intelligence in higher education: a qualitative study. In: Journal of Applied Research in Higher Education. 2024, 16(4), 1228-1245. ISSN 2050-7003. Available at: <https://doi.org/10.1108/JARHE-09-2023-0426>

- Jarvis, P., 2012. Teaching, learning and education in late modernity: The selected works of Peter Jarvis. London: Routledge, 2012. ISBN Available at: <https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203802946>

- Jones, C., Penaluna, K. and Penaluna, A., 2019. The promise of andragogy, heutagogy and academagogy to enterprise and entrepreneurship education pedagogy. In: Education and Training. 2019, 61(9), 1170-1186. ISSN 0040-0912. Available at: <https://doi.org/10.1108/ET-10-2018-0211>

- Kay, D. and Kibble, J., 2016. Learning Theories 101: Application to everyday teaching and scholarship. In: Advances in Physiology Education. 2016, 40(1), 17-25. ISSN 1522-1229. Available at: <https://doi.org/10.1152/advan.00132.2015>

- Knowles, M. S., Holton, E. F. and Swanson, R. A., 2005. The adult learner the definitive classic in adult education and human resource development. Elsevier, 2005. ISBN 1856178110.

- Kokotsaki, D., Menzies, V. and Wiggins, A., 2016. Project-based learning: A review of the literature. In: Improving Schools. 2016, 19(3), 267-277. ISSN 1475-7583.

- Kolb, A. Y. and Kolb, D. A., 2005. Learning styles and learning spaces: Enhancing experiential learning in higher education. In: Academy of Management Learning and Education. 2016, 4 (2), 193-212. ISSN 1944-9585.

- Kolb, A. and Kolb, D. 2018. Eight important things to know about the experiential learning cycle. In: Australian Educational Leader. 2018, 40(3), 8-14. ISSN 2210-5328. Available at: <https://search.informit.org/doi/10.3316/informit.192540196827567>

- Makani and Rajan, M. N., 2016. Understanding business concepts through application: the pedagogy of community-engaged learning. In: Journal of Business and Educational Leadership. 2016, 6(1), 82-. ISSN 2152-8411.

- McNally, J. J., Piperopoulos, P., Welsh, D. H. B., Mengel, T., Tantawy, M. and Papageorgiadis, N., 2020. From pedagogy to andragogy: Assessing the impact of social entrepreneurship course syllabi on the millennial learner. In: Journal of Small Business Management. 2020, 58(5), 871-892. ISSN 1540-627X. Available at: <https://doi.org/10.1080/00472778.2019.1677059>

- Mononen, M., Havu-Nuutinen, S. and Haring, M., 2023. Student teachers’ experiences in teaching practice using team teaching in flexible learning space. In: Teaching and Teacher Education. 2023, 125, 104069. ISSN 0742-051X. Available at: <https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2023.104069>

- Moore, T. L., 2014. Community-university engagement: A process for building democratic communities. Jossey-Bass, 2014. ISBN 1118917456.

- Mort, S. and Weerawardena, J., 2006. Networking capability and international entrepreneurship. In: International Marketing Review. 2006, 23(5), 549-572. ISSN 0265-1335.

- Parrish, P. E., Wilson, B. G. and Dunlap J. C., 2011. Learning experience as transaction: A framework for instructional design. In: Educational Technology. 2011, 51(2), 15-22. ISSN 1436-4522.

- Pineda, P. and Mishra, S., 2023. The semantics of diversity in higher education: Differences between the global north and global south. In: Higher Education. 2023, 85, 865-886. ISSN 1573-174X. Available at: <https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-022-00870-4>

- Popov, V., Brinkman, D., Biemans, H. J., Mulder, M., Kuznetsov, A. and Noroozi, O., 2012. Multicultural student group work in higher education: An explorative case study on challenges as perceived by students. In: International Journal of Intercultural Relations. 2012, 36(2), 302-317. ISSN 1873-7552. Available at: <https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2011.09.004>

- Purcell, J. W., Pearl, A. and Van Schyndel, T., 2021. Boundary spanning leadership among community-engaged faculty: An exploratory study of faculty participating in higher education community engagement. In: Engaged Scholar Journal. 2021, 6(2), 1-30. ISSN 2368-416X. Available at: <https://doi.org/10.15402/esj.v6i2.69398>

- Sá, M. J. and Sandro S., 2018. Transversal competences: Their importance and learning processes by higher education students. In: Education Sciences. 2018, 8(3), ISSN 2227-7102. Available at: <https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci8030126>

- Savery, J. R., 2006. Overview of problem-based learning: Definitions and distinctions. In: Interdisciplinary Journal of Problem-Based Learning. 2006, 1(1). ISSN 1541-5015. Available at: <https://doi.org/10.7771/1541-5015.1002>

- Seel, N. M., Lehmann, T., Blumschein, P. and Podolskiy, O. A., 2017. Instructional design for learning: Theoretical foundations. Sense Publishers, 2017. ASIN B06ZZN47YD.

- Smart, K. L., Witt, C. and Scott, J. P., 2012. Toward learner-centered teaching: An inductive approach. In: Business Communication Quarterly. 2012, 75(4), 392-403. ISSN 2329-4922. Available at: <https://doi.org/10.1177/1080569912459752>

- Smith, L. B. and MacGregor, J. T., 1992. What is collaborative learning? In collaborative learning: A sourcebook for higher education. In: National Center on Postsecondary Teaching, Learning, and Assessment (NCTLA), 1992. [online]. [cit. 2024-04-10]. Available at: <https://teach.ufl.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/WhatisCollaborativeLearning.pdf>

- Stronge, J. H., 2018. Qualities of effective teachers. ASCD, 2018. ISBN 1416625895.

- Taylor, D. C. M. and Hamdy, H., 2013. Adult learning theories: Implications for learning and teaching in medical education: AMEE Guide No. 83. In: Medical Teacher. 2013, 35(11), e1561-e1572. Available at: <https://org/10.3109/0142159X.2013.828153>

- Thomas, J. W., 2000. A review of research on project-based learning. California: In: The Autodesk Foundation, 2000. [online]. [cit. 2024-04-17]. Available at: <https://www.k12reform.org/foundation/pbl/research>

- Tillväxtverket, 2018. Nya trender inom export och import (Pub.nr.: 0261), 2018. [online]. [cit. 2024-02-10]. Available at: <https://tillvaxtverket.se/tillvaxtverket/publikationer/arkiveradepublikationer/publikationer2018/nyatrenderinomexportochimport.1310.html>

- Wurdinger, S., Haar, J., Hugg, R. and Bezon, J., 2007. A qualitative study using project-based learning in a mainstream middle school. In: Improving Schools. 2007, 10(2), 150-161. ISSN 1475-7583. Available at: <https://doi.org/10.1177/1365480207078048>

- Zahra, S. A., Gedajlovic, E., Neubaum, D. O. and Shulman, J. M., 2009. A typology of social entrepreneurs: motives, search processes and ethical challenges. In: Journal of Business Venturing. 2009, 24(5), 519-532. ISSN 1873-2003. Available at: <https://doi:10.1016/j.jbusvent.2008.04.007>

Kľúčové slová/Key words

course design, international marketing, internationalization, cultural diversity, business education, instructional design, real-client projects

dizajn predmetu, medzinárodný marketing, internacionalizácia, kultúrna rozmanitosť, podnikateľské vzdelávanie, dizajn inštrukcií, projekty s reálnymi klientmi

JEL klasifikácia/JEL Classification

I23, M31, M53

Résumé

Redizajn predmetu Medzinárodný marketing: Zapojenie rôznorodej triedy do projektov skutočných klientov

Svet sa mení. Pedagógovia v oblasti podnikového riadenia vrátane marketingu čelia výzve poskytovať relevantné vzdelávanie. Študenti ako primárne zainteresované strany sa zaujímajú o kompetencie, ktoré im umožnia (konkurenčnú) zamestnateľnosť. Organizácie (zamestnávatelia) znižujú svoju ochotu zaškoľovať nových zamestnancov priamo na pracovisku a požadujú ich okamžitý prínos pre ciele organizácie. Spoločnosť čoraz viac zdôrazňuje, že vysokoškolské vzdelávanie musí prekročiť rámec vzdelávania a výskumu a prejsť na tretie poslanie, ktorým je priamy prínos k rozvoju komunity a hospodárskemu rozvoju. Tento príspevok sa zaoberá (re)dizajnom predmetu Medzinárodný marketing založeného na experimentálnom učení a dizajne výučby. Predmet je integrovaný do miestnej podnikateľskej komunity a využíva ako výhodu rôznorodú populáciu študentov, aby reagoval na výzvy, ktorým čelia miestne podniky pri realizácii podnikateľskej internacionalizácie. Účinky (re)dizajnu predmetu sa merajú prostredníctvom hodnotení predmetu počas posledného trojročného obdobia. Cieľom príspevku je prispieť do kolegiálnej diskusie o zapojení podnikateľskej komunity s cieľom zvýšiť relevantnosť vzdelávania, ako aj podeliť sa o nápady na systematický návrh a realizáciu predmetu.

Recenzované/Reviewed

30. May 2024 / 27. September 2024