This paper examines the evaluation of advertising with particular reference to possible sexism and the differences in response among individuals of different religious affiliation, religiosity, and origin. Religion, religiosity and migration background make small explanatory contributions to the evaluation of advertising in four relevant dimensions, but in the overall picture prove to be less significant than sociodemographic and psychographic criteria beyond religion and origin.

1 Introduction

In 2016, Germany experienced a hefty public discussion on sexism in advertisements. Despite an enormous public outcry and the federal governments’ strong determination, the political parties were unable to pass a new federal law due to rather controversial positions. Instead, selected regulations were enacted at the state and local level to prevent any display of content deemed sexually discriminatory on public advertising spaces.

Along the discussion, all stakeholders argued rather emotionally, largely based on their political values and believes. Real data on the population’s perceptions, experiences and expectations on sexism in advertisement were missing. Accordingly, we decided to bring more light into the emotional debate and provide empirical data on which contents are really perceived sexually discriminatory by the German population and which not.

2 Conceptual framework

Discrimination occurs almost everywhere and can refer to a wide variety of personal characteristics like sex, age, origin etc. Sexism includes all gender-related forms of discrimination. For reasons of simplification, in the present studies sexism was examined exclusively in connection with contents perceived as misogynistic.

Besides analyzing the interviewees’ general attitude concerning advertisements, the authors also checked for the big five personality traits (Costa and McCrae 1985; McCrae and John 1992; Rammstedt et al. 2004) to get more comprehensive insights on the participants’ media consumption as well as their assessment of specific advertisements.

3 Empirical studies

3.1 Research approach and design

A partially standardized approach was used to collect the relevant constructs. Open-ended questions were used to ascertain whether and, if so, what the respondents had personally been pleased or annoyed about in relation to advertising in the past two years (using the Critical Incident Technique based on Flanagan (1954)). These questions were asked before the issue of sexist or discriminatory advertising had even been raised, so it is possible to read from the sum and distribution of responses the extent to which the population itself has the issue of sexism on its mind.

The other questions were quantitative in nature. In the form of rating scales, respondents had to answer the following blocks of items on the following sets of questions:

• extent of perceived annoyance by advertising in the various media (TV, print, brochures, posters, radio, email, internet advertising),

• self-rating on personality type (Big Five in the version of Rammstedt et al. (2004)),

• 11-item battery for the assessment of advertising, which was compiled on the basis of explorative preliminary research,

• media consumption (hours/minutes daily) in relation to TV, radio and digital media, and

• 5 items for assessment (aesthetics, fit to advertised product, degree of erotic charge, degree of associated sexism, desire to ban such advertising).

With the exception of the recording of temporal media consumption, a scale with expressions from 0 (not at all, does not apply, etc.) to 10 (completely, completely applies, etc.) was given for all ratings. The authors decided for this scaling to overcome the arbitrariness of a scale selection, as it is the case with the widely used 5-7 or 9-point Likert scales. Since the respondents are used to thinking in the decimal system from everyday life, no cognitive effort is required to transfer a personal assessment into a numerical response value. This eliminates a possible source of error in the survey, and at the same time there are no refusals to answer due to „cumbersome“ scale specifications. Scaling in the decimal system, in which only the two extremes are labeled and which at the same time dispenses with any further verbalization of gradations, is becoming more and more widespread in empirical research in many disciplines (Osman et al. 1994; Miles et al. 2011), whereby it seems to be irrelevant for the respondents’ ability to provide information whether a scaling from 0 to 10 or 0 to 100 is used (e.g., Lorig et al. 1989), since the subjects mostly answer in increments of ten on the 100 scale.

Four further questions served as a summary assessment by the survey participants. The survey concluded with 8 questions about the person (age, gender, school-leaving qualification, location of residence, satisfaction with current living situation, migration background, self-assessment of religiosity, religious affiliation).

3.2 Method and sampling

The authors conducted an empirical study in two waves, the first one ending in Q1 2017 and the second one five years later in Q1 2022. In both waves the same questionnaire was used, but the empirical methodologies were different due to the corona pandemic. While the first wave was conducted as a face-to-face study with 1460 cases, the second wave was an online survey resulting in 900 cases. In both cases, the survey was conducted as a convenience sample, leaving it up to the interviewers to select the respondents, but with quota specifications, thus ensuring that the resulting sample corresponds to the average of the German population in terms of the three characteristics age, gender and level of education. Further quota characteristics were not specified due to the associated increasingly complex search for participants, but it was determined that a maximum of one person per family could be interviewed.

3.3 Comparison of the two waves of the study

Comparing the two survey dates reveals similarities, but also significant differences in the sample:

| year (wave) of survey | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2017 (n= 1449) | 2022 (n= 900) | |||

| crosstabs, percentage | contingency coefficient | p | ||

| Sex | ||||

| female | 52.0% | 49.8% | .062 | .011 |

| male | 48.0% | 49.7% | ||

| diverse | .0% | .6% | ||

| Migration background | ||||

| yes | 13.4% | 9.9% | .052 | .011 |

| no | 86.6% | 90.1% | ||

| mean, variance analysis | F (Anova) | p | ||

| Age (Years) | 39.0 | 42.6 | 22.459 | .001 |

| Index Education (1 = secondary school - 5 = university) | 2.7 | 2.6 | 4.477 | 0.034 |

| Satisfaction with the situation in life (0=min - 10=max.) | 7.8 | 7.4 | 33.355 | 0.001 |

Table 1: Comparison of the 2017 and 2022 samples

Source: Authors

As Table 1 shows, the proportion of genders is largely identical in both studies, and the same applies to the index of educational qualifications surveyed. In contrast, there are slightly fewer respondents with an immigrant background in the 2022 study; at the same time, the average age is a considerable 3.5 years higher. Life satisfaction is somewhat lower in 2022 than in 2017.

The first reason for the differences found here is the change in method. Persons with a migration background have a somewhat lower propensity to participate in surveys. While this can be partially compensated for in the face-to-face survey by friendly follow-up from the personal interviewers, this possibility is missing in the online survey, so that the resulting proportion of people in the sample is lower. Another influencing factor is the covid pandemic existing in 2022. This may partly explain the overall decline in life satisfaction. Parallel unaided surveys also show that younger individuals, often still in education, devoted so much time to online media during the pandemic that any further survey focused on the online sector met with a reduced willingness to participate. In contrast, the willingness of older target groups to participate remained unchanged, so that the result is an increased average age of the sample, even though the quota characteristics specified for contacting potential respondents were identical to those of 2017.

In summary, in terms of individual time spent on the survey, gender distribution, and education level, there are good matches between the samples from the two survey dates. There are significant, but nevertheless explainable, differences in the proportion of people with an immigrant background, the average age and satisfaction with the living situation. Overall, under these conditions, the summary and comparative evaluation of the collected data with respect to the central constructs such as attitudes toward advertising, sexist advertising, the Big Five, and others appear justifiable. It will be necessary to clarify in a follow-up survey planned as another online study whether the findings presented below prove to be stable.

3.4 Results and discussion

3.4.1 Personality dimensions

An exploratory factor analysis (principal component analysis with varimax rotation) yields the expected five personality dimensions. KMO is 0.534, and the communalities of all 10 items range from 0.572 to 0.757.

| initial eigenvalues | rotated sum of squared loadings | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| component | total | % of variance | cum. variance % | total | % of variance | cum. variance % |

| 1 | 1.856 | 18.555 | 18.555 | 1.577 | 15.770 | 15.770 |

| 2 | 1.351 | 13.511 | 32.066 | 1.362 | 13.623 | 29.393 |

| 3 | 1.259 | 12.592 | 44.658 | 1.324 | 13.240 | 42.634 |

| 4 | 1.187 | 11.871 | 56.529 | 1.303 | 13.035 | 55.668 |

| 5 | 1.110 | 11.103 | 67.632 | 1.196 | 11.963 | 67.632 |

| 6 | 0.894 | 8.941 | 76.572 | |||

| 7 | 0.682 | 6.818 | 83.390 | |||

| 8 | 0.589 | 5.891 | 89.282 | |||

| 9 | 0.589 | 5.888 | 95.170 | |||

| 10 | 0.483 | 4.830 | 100.000 |

Extraction method: principal component analysis

Table 2: Variance explanation by five personality dimensions

Source: Authors

The five factors explain 67.6 percent of the initial variance of the items (cf. Table 2), and the loading matrix largely corresponds to the simple structure and exactly replicates the assignment of the items, as postulated by Rammstedt et al. (2004).

| component | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| [3.01] I am rather reticent and reserved | .831 | ||||

| [3.02] I trust others easily, believe in the good in people | .771 | ||||

| [3.03] I am easy-going and avoid effort if possible. | .800 | ||||

| [3.04] I am relaxed, I do not let myself be upset by stress | -.840 | ||||

| [3.05] I have rather little interest in art | -.834 | ||||

| [3.06] I am sociable and outgoing | -.827 | ||||

| [3.07] I tend to criticize others | -.697 | ||||

| [3.08] I make a point of completing tasks thoroughly | -.753 | ||||

| [3.09] I get nervous and insecure easily | .723 | ||||

| [3.10] I am creative and have an active imagination | .809 |

Method: principle components analysis with varimax rotation

Rotation converged in 5 iterations.

Table 3: Loading structure of the five personality dimensions

Source: Authors

For further analysis, sum indices were calculated from the original items in the correct polarity (with two Items each representing one dimension), as they are based on the scaling of the original items and are thus easier to interpret than the standardized factor scores of SPSS.

3.4.2 Basic attitude towards advertising

The eleven items assessing advertising were exploratively tested for dimensionality using factor analysis. KMO yields a value of 0.759, the eigenvalue criterion leads to the following four dimensions that together explain 66.15 percent of the baseline variance (see Table 4).

| initial eigenvalues | rotated sum of squared loadings | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| component | total | % of variance | cum. variance % | total | % of variance | cum. variance % |

| 1 | 3.052 | 27.748 | 27.748 | 2.735 | 24.867 | 24.867 |

| 2 | 2.054 | 18.675 | 46.422 | 1.603 | 14.572 | 39.439 |

| 3 | 1.142 | 10.384 | 56.806 | 1.540 | 14.004 | 53.443 |

| 4 | 1.029 | 9.352 | 66.158 | 1.399 | 12.715 | 66.158 |

| 5 | .795 | 7.227 | 73.385 | |||

| 6 | .725 | 6.593 | 79.978 | |||

| 7 | .615 | 5.595 | 85.574 | |||

| 8 | .496 | 4.507 | 90.081 | |||

| 9 | .463 | 4.210 | 94.291 | |||

| 10 | .341 | 3.104 | 97.395 | |||

| 11 | .287 | 2.605 | 100.000 |

Extraction method: principal component analysis

Table 4: Variance explanation by four dimensions of attitude towards advertising

Source: Authors

The loadings of the items on the four factors largely correspond to the simple structure, and the assignments of the items to the four dimensions are immediately self-explanatory (Table 5). The four dimensions express:

• degree of rejection of advertising due to sexist and other content,

• positive view of advertising as being useful for purchase decisions, entertaining, etc.,

• perceived annoyance due to the volume of advertising, and

• demand for government regulation of advertising.

| component | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| [4.01] There is too much advertising in the media overall. | .865 | |||

| [4.02] I think advertising is informative. | .736 | |||

| [4.03] Too much misogynistic content is shown in adverts. | .871 | |||

| [4.04] Most of the time I find ads just annoying. | -.323 | .783 | ||

| [4.05] Advertising can help you make purchasing decisions. | .672 | |||

| [4.06] There is too much sexist content in advertising. | .868 | |||

| [4.07] The legislature should regulate advertising more closely. | .336 | .713 | ||

| [4.08] I reject advertising with erotic content. | .593 | |||

| [4.09] When I think of advertising, I think of funny and entertaining content. | .695 | |||

| [4.10] The state should stay out of advertising issues. | -.865 | |||

| [4.11] Advertising does not sufficiently respect the dignity of women.. | .858 |

Method: principle components analysis with varimax rotation

Rotation converged in 5 iterations.

Table 5: Loading structure of the four dimensions of attitude towards advertising (loadings below .3 are suppressed)

Source: Authors

3.4.3 Descriptive analysis of the relationship between migration background, religiosity and religious affiliation

In the descriptive evaluations for the analysis of religious affiliation the three groups „without“ (religion), „Christian“ and „Islamic“ can be included. The 32 people distributed among „other“ religions form a heterogeneous sample, with none of the named religions representing a sufficient sample to conduct sufficiently reliable evaluations in this regard.

As Table 6 shows, there is a clear and highly significant (Anova, F= 594.43, p<0.001) correlation between religious affiliation and self-perceived religiosity.

| [22] religion | mean religiosity | n | std.-dev. |

|---|---|---|---|

| None | .62 | 586 | 1.365 |

| Christian | 4.58 | 1667 | 2.706 |

| Islamic | 5.56 | 64 | 2.728 |

| total | 3.60 | 2317 | 2.999 |

Table 6: Self-assessment of religiosity according to religious affiliation

(scale from 0…10)

Source: Authors

The variances of religious affiliation of the groups are inhomogeneous (Levene’s test: p<0.001), a posthoc test for groups with inhomogeneous variance (Tamhane T-2) performed subsequently shows that all subgroups differ significantly from each other.

It can be stated that members of Islam indicate a higher individual religiosity than members of the Christian religion. In the German national territory, it can be assumed that a large proportion of persons with Islamic religious affiliation have a migration background. Table 7 confirms this relationship; the corresponding contingency coefficient is 0.395 (p<0.001).

| [19] migration background | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| yes | no | total | |||

| [22] religion | none | n | 74.0 | 512.0 | 586.0 |

| expected | 69.6 | 516.4 | 586.0 | ||

| Christian | n | 141.0 | 1526.0 | 1667.0 | |

| expected | 197.9 | 1469.1 | 1667.0 | ||

| Islamic | n | 60.0 | 4.0 | 64.0 | |

| expected | 7.6 | 56.4 | 64.0 | ||

| Total | n | 275.0 | 2042.0 | 2317.0 | |

| expected | 275.0 | 2042.0 | 2317.0 |

Table 7: Crosstabs: Relationship between religion belonging and migration background

Source: Authors

Based on the preceding analyses, it can be assumed that there is also a disproportionate correlation between migration background and self-rated religiosity. As table 8 shows, the self-rated religiosity of persons with an immigrant background (on a scale of 0 to 10) is 3.90, which is 9.2 percent higher than that of persons without an immigrant background. However, the difference is not statistically significant (Anova, F=3.077, p=0.080).

| [19] migration background | mean | n | std.-dev. |

|---|---|---|---|

| yes | 3.90 | 283 | 3.154 |

| no | 3.57 | 2066 | 2.977 |

| total | 3.61 | 2349 | 3.000 |

Table 8: Self-assessment of religiosity (scale from 0…10) according to existence of migration background

Source: Authors

Thus, it can be assumed overall that religious belonging has a greater explanatory contribution to the individual´s religiosity than the presence of an immigrant background.

A multiple regression analysis with the dummy variables migration background (0=no, 1= yes) and religious affiliation (0=none, 1= Christian, 2= Islamic) as independents and religious affiliation (interval-scaled 0…10) as a dependent supports this finding:

| non standardized coefficients | standardized coefficients | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| regression coefficient B | std.-dev. | beta | T | Sig. | |||

| 1 | (constant) | .120 | .328 | .367 | .714 | ||

| [19] migration background | .386 | .160 | .042 | 2.406 | .016 | ||

| [22] religious affiliation | 3.560 | .108 | .569 | 32.896 | <.001 |

a. dependent: [21] self-assessment of religiosity

Table 9: Regression analysis: Self-Assessment of religiosity as a function of religious affiliation and migration background

Source: Authors

The beta value for religious affiliation is 0.569, which is about 14 times higher than that for migration background. However, this analysis still yields a significance of p=0.016 even for religious affiliation.

3.4.4 Relationship between personality traits and assessment of advertising

We further examined the relationship between the five personality dimensions and the four dimensions of advertising judgment using correlation analyses (see table 10).

| extraversion | openness | conscientiousness | neuroticism | agreeableness | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rejection due to sexism | Pearson-corr. | .063 | .149 | -.010 | .095 | .087 |

| p | .002 | .001 | .619 | .001 | .001 | |

| Advertising useful and entertaining | Pearson-corr. | -.064 | .019 | -.015 | .033 | .120 |

| p | ||||||

| Amount of advertising distracting | Pearson-corr. | -.026 | -.014 | -.005 | .050 | -.050 |

| p | .213 | .496 | .820 | .015 | .016 | |

| Government regulation called for | Pearson-corr. | .014 | -.024 | -.016 | .123 | .048 |

| p | .490 | .247 | .427 | .001 | .021 |

Table 10: Correlations between personal traits and the four dimensions of judging ads

Source: Authors

Due to the relatively large number of participants, even small correlations turn out to be significant. In order not to overemphasize arbitrary detailed results, we will limit our interpretation to correlations that are at least in the range of 0.1 or higher.

Looking column-wise, we find that the personality trait extraversion has some correlations with the evaluation of advertising that seem plausible, but overall are very weak. In contrast, openness is correlated with r=0.149 and highly significantly with rejection of sexist advertising. Openness is thus not expressed by being open to sexist advertising, but by being open to modern anti-discriminatory attitudes such as rejecting sexism. Conscientiousness of individuals does not explain either approving or disapproving attitudes toward advertising. Neuroticism is associated to a relevant and significant extent with persons rejecting sexism and also demanding regulations from the state in this regard. Finally, agreeableness is the only personality dimension positively correlated with the notion that advertising can also be entertaining and useful.

Overall, the highly explainable correlations show that the measurement of personality traits with the short scale of the Big Five is also suitable for providing plausible findings for the special case of the assessment of advertising.

3.4.5 Relationship between religion and personality traits

The preceding analysis of the correlations with the advertising evaluation can be seen as a validation of the measurement of the big five. This makes it seem appropriate to use the Big Five also for the consideration of possible religion-related differences in the sample (note [1]).

| [22] religion | extraversion | openness | conscientiousness | neuroticism | agreeableness | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| none (n=586) | mean | 2.06 | 0.26 | 3.57 | -1.61 | 1.77 |

| std.dev. | 4.32374 | 3.78166 | 4.04509 | 4.17211 | 4.79161 | |

| Christian (n=1667) | mean | 2.32 | 0.73 | 4.19 | -1.45 | 1.08 |

| std.dev. | 4.24384 | 3.70938 | 3.85639 | 4.03637 | 4.84005 | |

| Islamic (n=64) | mean | 1.89 | 0.05 | 1.99 | -1.55 | 1.57 |

| std.dev. | 4.40821 | 3.89558 | 3.96762 | 4.28519 | 4.96645 | |

| total | mean | 2.24 | 0.60 | 3.97 | -1.49 | 1.27 |

| std.dev. | 4.26880 | 3.73808 | 3.92996 | 4.07688 | 4.83881 |

Table 11: Analysis of personality traits with different religious belonging

Source: Authors

An accompanying analysis of variance shows that there is no significant difference between the „religious groups“ for extraversion and neuroticism. In contrast, openness (F=4.182, p=0.015) proves to be significant, whereby persons belonging to Islam rate themselves as less open than Christians and persons without religion. Highly significant (F= 14.056, p<0.001) is the same relationship with respect to conscientiousness.

There is another significant difference (F=4.581, p= 0.010) with respect to agreeableness, but with the opposite direction: here, members of Islam rate themselves as more agreeable than adherents of Christianity. Interestingly, people „without“ religion assign themselves the highest value for agreeableness.

In this context, it should be emphasized once again that this is not a reflection of third-party opinions, which may reflect stereotypes about other religious groups, but rather self-assessments. The respondents were not even aware of the fact that the surveys carried out would make distinctions according to religion (or the existence of a migration background) when they submitted their statements.

3.4.6 Relationship between religion and the assessment of advertising

The relationships were tested using analysis of variance, with religion as the independent variable and the four dimensions of advertising as the dependent variables. The four dimensions identified in 3.4.2 were stored in SPSS as factor scores. These are interval-scaled and at the same time standardized, i.e. they have a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 1. In the case of the results shown in Table 12, a value of greater than 0 means that the respective factor applies above average to this group and vice versa.

The variances are not homogeneous with respect to „rejection due to sexism“ (Levene test, p>0.001) and „advertising useful and entertaining“ (p=0.014), but homogeneous with respect to „amount of advertising disturbs“ (p=0.968) and „government regulation demanded“ (p= 0.156).

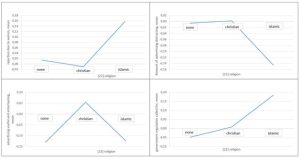

Visualizing the values for the three groups (no religion, Christian, Islamic) shows: „No-“ and Christian religion strongly resemble each other in three dimensions, only in the dimension „advertising useful and entertaining“ persons with Christian background agree more strongly. Followers of Islam differ from „Christian“ persons in all four dimensions. The assessments of the followers of Islam do not necessarily correspond to expectations. They reject sexism and are more likely than average to call for state regulation, but they themselves feel less disturbed by advertising.

Table 12: Religious affiliation and assessment of advertisement

Source: Authors

Analysis of variance shows that a significant difference between the three groups can only be assumed for the dimension „advertising useful and entertaining“ (F=7,962, p<0,001); this finding is also true for the corresponding posthoc tests (without picture).

In summary, it can be stated that people of different religious affiliations differ significantly only in that adherents of Christianity also attribute more positive aspects („useful and entertaining“) to advertising than do adherents of Islam or people with no religious affiliation. In the other dimensions of the assessment of advertising, there are indications of religion-specific differences, but these are not statistically significant in the present study.

In contrast, if we look at the self-rating of religiosity (irrespective of which religion is involved), more significant correlations emerge. With increasing religiosity, sexist advertising is increasingly rejected, but surprisingly advertising is also rated more strongly as potentially useful and entertaining. Completely independent of the degree of religiosity, on the other hand, is the finding that the amount of advertising is perceived as disturbing (see Table 13).

| [21] degree of personal religiosity (n= 2349) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Rejection of ads due to sexism | Pearson-corr. | .135 |

| p | <.001 | |

| Advertising is useful and entertaining | Pearson-corr. | .102 |

| p | <.001 | |

| The amount of advertising is annoying | Pearson-corr. | -.019 |

| p | .359 | |

| Regulatory control by the state is needed | Pearson-corr. | .064 |

| p | .002 |

Table 13: Assessment of advertising as a function of the degree of personal religiosity

Source: Authors

Further analyses confirm that people’s religiosity is more significant for their expressed attitudes toward advertising than their affiliation with a particular religion. For this purpose, let us consider a multiple regression analysis with religiosity (0…10) and the dummy variable religion (0=none, 1=Christian, 2=Islamic) as independent variables and rejection of advertising due to sexist content as exemplary dependent. The regression function yields a correlation of R=0.162. Both independents are significant influencing factors for the respondents’ judgment, but beta is much higher for religiosity than for religious affiliation (Table 14).

| regression coefficient B | std.-dev. | Beta (standardized) | T | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (constant) | -.060 | .040 | -1.503 | 0.133 | |

| [21] degree of personal religiosity | .066 | .008 | .197 | 7.919 | <.001 |

| [22] religious affiliation | -.227 | .052 | -.109 | -4.385 | <.001 |

dependent: rejection of ads due to sexism

Table 14: Multiple regression analysis: Rejection of advertising due to sexism as a function of the degree of personal religiosity and religious affiliation

Source: Authors

3.4.7 Assessment of advertising depending on the presence of a migration background

If we look at the influence of migration background on the assessment of advertising, the picture is different from that for religion as an independent variable: Whereas there was a significant difference in the judgment that „advertising is useful and entertaining“, there is a significant difference (Anova, F=8,915, p=0,003) here in the rejection of advertising on the basis of sexism 14). There are no significant correlations with regard to the other variables of the evaluation of advertising.

The Levene test consistently yields the result of homogeneous variances. In absolute terms, the differences between persons with and without a migration background are small (Table 15).

| [19] migration background | [19] migration background | Rejection of ads due to sexism | Advertising is useful and entertaining | The amount of advertising is annoying | Regulatory control by the state is needed |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| yes (n=283) | mean | .1662 | .0358 | -.0117 | .0446 |

| std.-dev. | .98363 | .99292 | .96868 | .93021 | |

| no (n=2066) | mean | -.0228 | -.0049 | .0016 | -.0061 |

| std.-dev. | 1.00031 | 1.00110 | 1.00443 | 1.00924 |

Table 15: Mean differences in the assessment of advertising between persons with and without a migration background

Source: Authors

3.4.8 Condensed analysis

Beyond the individual results presented, it is now interesting to see to what extent various independents interact to influence the assessment of advertising as a dependent variable.

We selected openness, neuroticism and agreeableness as psychographic independents for the personality traits on the basis of the previous analyses and supplemented this with the sociodemographic characteristic of age; in addition, religiosity (self-assessment) and the presence of a migration background were included as independents.

We conducted the analysis twice, once with the variable „rejection due to sexism“ and a second time with „advertising entertaining and useful“ as a dependent.

| regression coefficient B | std.-dev. | Beta (standardized) | T | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (constant) | -.078 | .120 | -.649 | .516 | |

| [21] degree of personal religiosity | .021 | .007 | .062 | 3.022 | .003 |

| [14] age | .012 | .001 | .214 | 10.299 | <.001 |

| [19] migration background | -.260 | .061 | -.085 | -4.235 | <.001 |

| openness | .149 | .020 | .149 | 7.565 | <.001 |

| neuroticism | .115 | .020 | .115 | 5.822 | <.001 |

| agreeableness | .074 | .020 | .074 | 3.757 | <.001 |

dependent: rejection of ads due to sexism

Table 16: Multiple regression analysis: Rejection of advertising due to sexism as a function of different personal characteristics

Source: Authors

Regression analysis yields an overall R of 0.311, and a parallel analysis of variance shows a highly significant result (F= 41.796, p<0.001). As table 16 shows, all the independents make a significant contribution to explaining the dependents. At the same time, it can be noted that the „simple” socio-demographic criterion age makes a significantly larger explanatory contribution than the other criteria. It is also worth noting that the psychographic personality traits openness and neuroticism are more important influencing factors than, for example, the presence of a migration background or the degree of personal religiosity.

The positive judgment dimension „advertising is useful and entertaining“ is far less well explained by the independents selected here than the critical dimension presented earlier. The overall R for all six independents is 0.179 (Anova: F=12.929, p<0.001). The coefficient table shows that for these dependents, personal agreeableness is the most significant influencing factor, followed by age (Table 17). All other influencing factors provide extremely small and/or non-significant contributions. In particular, it can be seen that religiosity and migration background hardly seem to be of any importance here.

| regression coefficient B | std.-dev. | Beta (standardized) | T | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (constant) | -.149 | .125 | -1.198 | .231 | |

| [21] degree of personal religiosity | .021 | .007 | .062 | 2.895 | .004 |

| [14] age | .006 | .001 | .098 | 4.534 | <.001 |

| [19] migration background | -.079 | .063 | -.026 | -1.247 | .213 |

| openness | .019 | .020 | .019 | .912 | .362 |

| neuroticism | .041 | .020 | .041 | 2.027 | .043 |

| agreeableness | .110 | .020 | .110 | 5.375 | <.001 |

dependent: Advertising is useful and entertaining

Table 17: Multiple regression analysis: judgement of advertising as „useful and entertaining“ as a function of different personal characteristics

Source: Authors

4 Conclusion

As a result of two largely comparable partial studies conducted in 2017 and 2022, we were able to determine that the assessment of advertising is based on four factors that can be interpreted well. The topic of potential misogyny or sexism in advertising represents a critical assessment dimension, but the sheer volume of advertising is also addressed and criticized. People also have different views on the demand for state regulation. Furthermore, however, advertising can also be judged positively, as it is seen as useful or entertaining.

In order not to myopically focus on the effects of religion, religiosity and migration background, which are of interest in this study, we also examined the respondents with regard to sociodemographic characteristics and, in particular, with regard to the psychographic personality dimensions of the OCEAN model („Big Five“). The survey and factor-analytical evaluation of these personality traits by means of the short questionnaire of Rammstedt et al. (2004) succeeded without any problems. Initial evaluations showed that people assess themselves differently in the Big Five depending on their religious affiliation. For example, members of Islam perceive themselves as less conscientious but more agreeable than Christians.

Different religions lead to slightly different judgments with regard to advertising, but overall the self-assessment of religiosity (independent of the religion practiced) is the more explanatory influencing factor for agreeing or disagreeing with advertising. The impact of a migration background is even smaller.

In the summarized analysis, age proves to be by far the most important determinant for a potential rejection of sexist advertising. Personality traits such as openness or neuroticism are also significant; religion, religiosity or migration background are only weakly related to a rejection of advertising based on sexism.

In explaining a positive judgment of advertising, personal agreeableness plays a role in the first place, followed by the age of the persons. Religiosity makes only a very small explanatory contribution here, and migration background makes no explanatory contribution at all.

We see our study as evidence that classical sociodemographic characteristics or well-documented psychographic criteria such as Openness, Neuroticism or Agreeableness have to be considered if one wants to explain the judgment of individuals towards socially relevant topics such as „sexism in advertising“. Religion, religiosity, or the existence of a migration background may provide significant variance explanations in individual contexts, but in terms of magnitude they are of secondary importance. To put it more drastically: Whether someone is neurotic or not has a greater influence on his views than his origin and his religion.

Poznámky/Notes

[1] We calculated the mean values of the five personality dimensions for the three groups „without religion“, „Christian“ and „Islamic“. The calculation was based on the sum indices formed from the two variables belonging to each dimension (see above). Since these were one negatively and one positively polarized variable with a scale of 0 to 10, the mean values shown range in a scale with theoretical values from -10 to +10.

Literatúra/List of References

- Barak, A., 2005. Sexual harassment on the internet. In: Social Science Computer Review. 2005, 23(1), 77-92. ISSN 0894-4393.

- Boddewyn, J. J. and Kunz, H., 1991. Sex and decency issues in advertising: General and international dimensions. In: Business 1991, 9-10, 13-20. ISSN 1873-6068.

- Bui, V., 2021. Gender language in modern advertising: An investigation. In: Current Research in Behavioral Sciences, 2021, 2, 1-68. ISSN 2833-0986.

- Chan, K, Li, Lyann, Diehl, S. and Terlutter, R., 2007. Consumers’ response to offensive advertising: a cross cultural study. In: International Marketing Review. 2007, 24(5), 606-628. ISSN 0265-1335.

- Costa, P. T. and McCrae, R. R., 1985. The NEO PI-R personality inventory manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources, 1985.

- Eisend, M., 2010. A meta-analysis of gender roles in advertising. In: Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science. 2010, 38(4), 418-440. ISSN 0092-0703.

- Eisend, M., 2019. Gender roles. In: Journal of Advertising. 2019, 48(1), 72-80. ISSN 1557-7805.

- Flanagan, J. C., 1954. The critical incident technique. In: Psychological Bulletin. 1954, 51(4), 327-359. ISSN 1939-1455.

- Ford, T. E., Boxer, C. F., Armstrong, J. and Edel, J. R., 2008. More than „just a joke“: The prejudice-releasing function of sexist humor. In: Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2008, 34, 159-170. ISSN 0146-1672.

- Fox, J., Cruz, C. and Lee, J. Y., 2015. Perpetuating online sexism offline: Anonymity, interactivity, and the effects of sexist hashtags on social media. In: Computers in Human Behavior. 2015, 52, 436-442. ISSN 0747-5632.

- Furnham, A. and Farragher, E., 2000. A cross-cultural analysis of sex-role stereotyping in television advertisements. In: Journal of Broadcasting and Electronic Media. 2000, 44(3), 415-436. ISSN 0883-8151.

- Grau, S. L. and Zotos, Y. C., 2016. Gender stereotypes in advertising: A review of current research. In: International Journal of Advertising. 2016, 35(5), 761-770. ISSN 0265-0487.

- Hatzithomas, L., Boutsouki, C. and Ziamou, P., 2016. A longitudinal analysis of the changing roles of gender in advertising. In: International Journal of Advertising. 2016, 35(5), 888-906. ISSN 0265-0487.

- Kacen, J. and Nelson, M., 2002. We´ve come a long way, baby – or have we? Sexism in advertising revisited. In: Gender and Consumer Behavior. 2002, 6, 291-307. ISSN 1596-9231.

- Khalil, A. and Dhanesh, G. S., 2020. Gender stereotypes in television advertising in the Middle East: Time for marketers and advertisers to step up. In: Business Horizons. 2020, 63(5), 671-679. ISSN 1873-6068.

- Knoll, S., Eisend, M. and Steinhagen, J., 2011. Gender roles in advertising: Measuring and comparing gender stereotyping on public and private TV channels in Germany. In: International Journal of Advertising. 2011, 30(5), 867-888. ISSN 1759-3948.

- LaTour, M. S. and Henthorne, T. L., 2003. Nudity and sexual appeals.

Understanding the arousal process and advertising response. In: Reichert, T. and Lambiase, J. (Eds.). Sex in advertising. 91-106, Mahwah, NJ:

Erlbaum, 2003. ISBN 0-8058-4117-2. - Lysonski, S. and Pollay, W. R., 1990. Advertising sexism is forgiven, but not forgotten: Historical, cross-cultural and individual differences in criticism and purchase boycott intentions. In: International Journal of Advertising. 1990, 9, 317-329. ISSN 1759-3948.

- McCrae, R. R. and John, O. P., 1992. An introduction to the five-factor model and its applications. In: Journal of Personality. 1992, 60(2), 175-215. ISSN 0022-3514.

- Miles, C. L., Pincus, T., Carnes, D., Taylor, S. J. C. and Underwood, M., 2011. Measuring pain self-efficacy. In: The Clinical Journal of Pain. 2011, 27(5), 461-70. ISSN 1536-5409.

- Mitchell, D., Hirschman, R., Angelone, D. J. and Lilly, R. S., 2004. A laboratory

analogue for the study of peer sexual harassment. In: Psychology of Women

2004, 28, 194-203. ISSN 0361-6843. - de, 2016a. Heiko Maas will Verbot sexistischer Werbung. 2016. [online]. [cit. 2023-02-14]. Available at: <https://www.spiegel.de/spiegel/vorab/heiko-maas-will-verbot-sexistischer-werbung-a-1086186.html>

- de, 2016b. Justizminister Maas fordert Verbot von sexistischer Werbung. 2016. [online]. [cit. 2023-02-14]. Available at: <https://www.sueddeutsche.de/medien/werbung-fdp-chef-lindner-an-spiessigkeit-kaum-zu-ueberbieten-1.2945363>

- de, 2019. Sexistische Werbung leider immer noch allgegenwärtig. 2019. [online]. [cit. 2023-02-14]. Available at: <https://www.frauenrechte.de/unsere-arbeit/themen/frauenfeindliche-werbung/aktuelles/3739-sexistischewerbung-leider-immer-noch-allgegenwaertig>

- Odekerken-Schröder, G., De Wulf, K. and Hofstee, N., 2002. Is gender stereotyping in advertising more prevalent in masculine countries? A cross-national

In: International Marketing Review. 2002, 19, 408-419. ISSN 0265-1335. - Osman, A., Barrios, F. X., Osman, J. R., Schneekloth, R. and Troutman, J., 1994. The pain anxiety symptoms scale: Psychometric properties in a community sample. In: Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 1994, 17(5), 511-522. ISSN 0160-7715.

- Paek, H. J., Nelson, M. R. and Vilela, A. M., 2011. Examination of gender-role portrayals in television advertising across seven countries. In: Sex Roles. 2011, 64(3/4), 192-207. ISSN 1573-2762.

- Plakoyiannaki, E. and Zotos, Y., 2009. Female role stereotypes in print advertising: Identifying associations with magazine and product categories. In: European

Journal of Marketing. 2009, 43, 1411-1434. ISSN 1758-7123. - Rammstedt, B., Koch, K., Borg, I. and Reiz, T., 2004. Entwicklung und Validierung einer Kurzskala für die Messung der Big-Five-Persönlichkeitsdimensionen in Umfragen. In: ZUMA-Nachrichten. 2004, 28(55), 5-28. ISSN 0941-167027.

- Reichert, T., 2002. Sex in advertising research: A review of content, effects, and functions of sexual information in consumer advertising. In: Annual Review of Sex Research. 2002, 13, 241-273. ISSN 1053-2528.

- Schroeder, J. E. and Zwick, D., 2004. Mirrors of masculinity: Representation and identity in advertising images. In: Consumption, Markets and Culture. 2004, 7, 21-52. ISSN 1477-223X.

- Sengupta, J. and Dahl, D. W., 2008. Gender-related reactions to gratuitous sex appeals in advertising. In: Journal of Consumer Psychology. 2008, 18, 62-78. ISSN 1057-7408.

- Shaw, A., 2014. The internet is full of jerks, because the world is full of jerks: What feminist theory teaches us about the internet. In: Communication and Critical/Cultural Studies. 2014, 11, 273-277. ISSN 1479-1420.

- Sun, Y., Lim, H., Jiang, Ch., Peng, J. Z. and Chen, X., 2010. Do males and females think in the same way? An empirical investigation on the gender differences in web advertising evaluation. In: Computers in Human Behavior. 2010, 26, 1614-1624. ISSN 0747-5632.

- Swim, J. K., Hyers, L. L., Cohen, L. L. and Ferguson, M. J., 2001. Everyday sexism: Evidence for its incidence, nature, and psychological impact from three daily diary studies. In: Journal of Social Issues. 2001, 57, 31-53. ISSN 0022-4537.

- Vaes, J., Paladino, P. and Puvia, E., 2011. Are sexualized women complete human beings? Why men and women dehumanize sexually objectified women.

In: European Journal of Social Psychology. 2011, 41, 774-785. ISSN 1099-0992. - Verhellen, Y., Dens, N. and de Pelsmacker, P., 2014. A longitudinal content analysis of gender role portrayal in Belgian television advertising. In: Journal of Marketing Communications. 2014, 22(2), 170-188. ISSN 1466-4445.

- Wolin, D. L., 2003. Gender issues in advertising-an oversight synthesis of research 1970-2002. In: Journal of Advertising Research. 2003, 39, 111-129. ISSN 1740-1909.

- Zotos, Y. C. and Tsichla, E., 2014. Female stereotypes in print advertising: A retrospective analysis. In: Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences. 2014, 148, 446-454. ISSN 1877-0428.

Kľúčové slová/Key words

advertising, marketing communication, sexism, culture

reklama, marketingová komunikácia, sexizmus, kultúra

JEL klasifikácia/JEL Classification

M31, M37

Résumé

Sexizmus v reklame – medzikultúrna analýza

Tento článok skúma hodnotenie reklamy s osobitným zreteľom na možný sexizmus a rozdiely v reakciách medzi jednotlivcami s rôznou náboženskou príslušnosťou, religiozitou a pôvodom. Náboženstvo, religiozita a migračný pôvod majú malý vysvetľujúci príspevok k hodnoteniu reklamy v štyroch relevantných dimenziách, ale v celkovom obraze sa ukazujú ako menej významné ako sociodemografické a psychografické kritériá mimo náboženstva a pôvodu.

Recenzované/Reviewed

3. March 2023 / 13. March 2023