The most up-to-date challenge of modern marketing is the need to incorporate sustainability principles into marketing strategies. Promoting the principles of sustainability requires setting environmental objectives at the enterprise level and devising marketing strategies that meet the environmental requirements and customer preferences. The article deals with two basic topics, the issue of environmental marketing against the background of customer preferences and generations of consumers, more precisely as they were profiled in Slovakia. Examining the preferences of customers of different generations aimed to prove that implementing environmental marketing principles is necessary. Although the aim of the research was to correlate selected findings with the preferences of the environmental objectives of different generations, the research that focused on the behavior of different generations of consumers under the sustainability concept revealed some original findings concerning the assessment of ethnocentrism under the sustainability concept.

Introduction

Designing marketing strategies for sustainable development is the most up-to-date challenge of modern marketing. To convince consumers that they should start to assess the goods and services they are interested in according to criteria they have not yet considered and, if only marginally, sure is a challenge for experienced marketers. To promote products and services in a different way means to take a specific information that has been uninteresting to consumers in the past, start to communicate it consistently and give it a new meaning. In the future, marketing communication must cover the origin of the product (producer and the country of origin) and often its components, how the manufacturer processes them and what technologies they use to do so, to what extent the product production affects or how much it burdens the environment, environmental performance, whether its use will be possible without restriction. At a high volume of emissions eg. passenger cars are prohibited from entering low-emission zones in cities., whether it meets the sustainability criteria of the supply chain, and ultimately whether the product and its packaging are fully or only partially recyclable. For agricultural products it will be necessary to communicate the way of breeding or cultivation, the use of biotechnologies, the degree of environmental burden and whether and what environmental criteria the product meets, more precisely, whether it meets or even exceeds the legislative criteria applicable to organic products.

Marketing strategies for sustainability

The types and sources of information that the customer is interested in are significantly different than it was a few years ago. Producers are obliged to give certain information on the packaging of products. Here, however, producers are rarely going beyond legislative standards because this depends on the demand for products that meet environmental criteria.

Classic customer-oriented marketing must monitor customer needs and preferences and analyze customer behavior (Kotler and Armstrong 2004). The authors did not anticipate that customers would need to be instructed in how to deal with products so that they could use the technologies they installed, and that sustainability factors, packaging materials used, linear supply chain or product recyclability will play an important role in marketing strategies. Nevertheless, classic marketing theories still apply, customer orientation remains a priority, but the customers have changed, and those who have not changed should be given the opportunity to make a change towards sustainability. In modern marketing, consumer care takes on a completely different meaning, and the consumer is the one that forces businesses to wonder why and how customers change their preferences. Knowing why this change is happening is a prerequisite for grasping the reasons why customers are changing their preferences. It goes without saying that this is linked to the existential factors of our civilization, but those who develop long-term strategies in line with sustainability requirements or will be leaders in the blue ocean strategies will be at an undeniable advantage. Not only because legislative standards are constantly tightening, but especially because the change in consumer preferences has already taken place.

Adaptation to changes is expected to take some time. It is undoubtedly a process that is difficult to analyze when assessing different customer approaches. In the context of sustainability analysis, they can demonstrate knowledge of the behavior of different generations of consumers, with consumer preferences evolving differently in different countries (differences can also be grasped within transnational groupings, states and regional characteristics) in relation to the purchasing power of the population, sustainability, including the knowledge of sustainability criteria and the availability of information on products and services in terms of sustainability. Influencing purchasing decisions with environmental criteria presupposes the choice, i.e. the existence of a range of products and services that actually meet these criteria. Today, there are practically no sectors that have not been touched by environmental criteria drafted since the 1980s (Meadows, Meadows and Randers 2012), (Technological limits, for example in the mining of products or in the chemical industry, have so far significantly affected the level of environmental burden and new ones are not yet available or are not implemented. This also applies to some service sectors that depend on transport costs).

Currently, there are products that meet and do not meet the sustainability criteria. The paradox of the present is that those products and services that do not meet sustainability criteria are more affordable, very often even cheaper, and they are traditional products well known to consumers. In those countries where the purchasing power of the population is low and the level of environmental education is low, the two factors also determine consumer preferences. These types of customers do not understand the environmental related information an if they do, it is not relevant to their needs and wants. Their response to products made with regard to sustainability principles is unambiguous, these products are simply too expensive, which means inaccessible. Influencing the pricing of such products requires legislative measures and opportunities that businesses find it difficult to find. There are governments that can and must introduce incentives to prioritize production according to the principles of sustainability. However, given the subject of this article, we will not discuss in detail the instruments of the governments which can be used to mitigate environmental impacts, but not to mention them would be a mistake.

Since 1995, authors who have been involved in environmental marketing (William and Wimsatt 1997), have intensively pointed out that change is necessary, meaning to devise long-term marketing strategies that can be implemented in terms of business sustainability criteria is essential. At the same time, changing company way of thinking is a way of gaining a competitive advantage in this area and making this advantage visible through marketing communications. This type of marketing activities has been given the attribute „green”, especially in order to evidently focus on waste-free technologies and adaptation of environmental principles. At the same time, environmental or, as we have indicated, „green marketing” is a newly emerging production and business philosophy that allows us to address sustainability issues. Environmental strategies, as we have tried to suggest, must be consistent and created on the principle of sustainability and accountability, only when they represent the added value that companies can and must pursue by implementing environmental strategies. The pretense of environmental responsibility does not pay off in the long run, and not only in cases where irresponsibility but fraud proves to be a tool for communicating environmental criteria.

However, there are still a number of issues that arise in the context of what is and is not sustainable in the long run. The basic value of the anthropocene era (The Anthropocene is a proposed geological epoch dating from the commencement of significant human impact on Earth’s geology and ecosystems, climate change) is responsibility (Jonas 1989). The Principle of responsibility – meaning the responsibility of businesses, states, multinational groups and isolated consumers. However, there are different concepts that are presented as environmental or sustainable, but they are not real. On the other hand, it is often not possible to take all factors into account, and when one is taken out, eg. recyclability or carbon footprint, sustainability principles are only declarative and not realistic. However, other factors that are currently not scientifically relevant and whose environmental impact is not evident in the context of today’s knowledge can also be introduced into the concept of sustainability. To make the situation even more complicated in the area of basic principles of sustainability, there is also a belief in man’s ability to handle, through technology, any problem (technocentrism) and in this context to communicate the unjustified fear of environmental or climate change.

One way that has been actively applied in the context of sustainability is the shortening of the supply chain (more precisely the linear preference) and the promotion of domestic products – in other words, the promotion of consumer ethnocentrism. Although originally ethnocentrism was associated only with the placement of foreign products on domestic markets, it made marketers examine the importance of the country of origin in the process of deciding to buy. The country of origin can then be regarded as a kind of ‘hint’, a promise of certain traditional qualities and the known characteristics of the product. The perception of the country of origin is an integral part of the domestic producer’s brand in both positive and negative terms. Customers’ preferences when buying foreign products can be influenced by confidence in foreign companies, branded products, but also by attitude to specific countries, both negative and positive (Tores and Gutiérrez 2007). However, in the context of sustainability, entnocentrism can play a positive role. The Slovak Republic is undergoing a process of intensive promotion of Slovak producers and marketing support for the purchase of goods that can be identified as „produced in Slovakia”. This has been happening for the last 4 years, which is a fairly long time to assess whether consumer behavior has changed in relation to sustainability. The purchase of Slovak products is being promoted despite the fact that Slovak government has never intensively built the image of Slovakia as the country of origin of the products. Efforts directed towards the purchase of products of Slovak origin began to be enforced at the governmental level mainly because at the turn of the millennium the Slovak Republic became an EU country, which according to statistical data (the share of Slovak food products in market basket) became a tool to influence the purchasing decisions of Slovaks. Businesses have started to use the image of a country as a promise of certain characteristics, but consumers, in pursuing the principles of sustainability and the increase in demand for organic products, have begun to evaluate products according to the criteria applicable to organic production. Ethnocentrism in this context is linked to the intensive promotion of sustainability principles and is one of the most effective tools of „green” marketing. It is also a mean of building the environmental sensitivity of consumers, but only if it is linked to the communication of environmental principles and objectives.

Typology of consumer generations in the Slovak Republic

The issue of sustainability, which is the subject of this paper, does not address the same level of members of all generations. However, segmentation and understanding of consumer preferences require knowledge of consumer generations. This is one of the key identifiers in reaching the potential consumer. The typology of generations is not uniform throughout the world, mainly because of the fact that membership of individual generations has specific characteristics related to the development of individual countries. The issue of generations is not a new topic in marketing (Hill 2002, Williams 1997, Bergh and Behrer 2015), but marketing analysts began to work with it intensively only in recent years. It has been shown that knowing precisely how to characterize individual generations of consumers is crucial for the correct setting of marketing activities. In addition to the typology of generations X, Y and Z, used mainly by American and Western European authors, also political and economic developments in the country in which the analyzes are made needs to be taken into consideration. The issue of generations has also been closely linked to questions concerning the relationship between modern technologies and their use. Therefore, they are used in practice in particular in the technology sectors. To use them in relation to the preference of sustainability principles is not yet standard in marketing, this will be unique in this paper.

The typology used in the Slovak Republic allows to grasp the meaning of the so-called „Slovak consumers”. In the following table, we present the generation typology, which was the basis for research of preferences of Slovak consumers (Smolka 2019).

| Generation typology | Generation name | Years |

| Basic generation typology | Generation X | 1966 – 1976 |

| Generation Y | 1977 – 1995 | |

| Generation Z | 1996 – 2012 | |

| Transitional generations | Generation „Baby Boomers“ | 1946 – 1965 |

| Generation „Husak's Children“ | 1974 – 1979 | |

| Generation „Millenials“ | 1980 – 2000 | |

| Generation „Snow Flakes“ | 2001 – | |

| Generation „Alfa“ | 2010 – |

Table 1: Generation typology

Source: Authors

We assume that the reader is familiar with the classic typology of generations that originated in the US. In Europe, however, after the Second World War, there were sharp and specific changes that differed from the processes that influenced the post-war generation in the US. The classical typology of generations was no longer sufficient, it was necessary to go deeper and to grasp the intergenerational differences and the distinctions concerning individual countries of the European continent. Every European country, not only the Slovak Republic (which belonged to the Czechoslovak Republic in the postwar period), had a large generation born after World War II. In this case, it is referred to as the „baby boomers“ generation. This generation was born in the time of economic prosperity and growth, and therefore did was in the center of attention of researchers (Cheung 2007). It is a generation that is very aggressive and adaptable, it grew up in a period of dramatic changes, and therefore it is associated with attitudes that its members changed or re-created. They are representatives of new and traditional values. In Czechoslovakia, the generation of Baby Boomers „built socialism” in atrial relations and their functioning only began to „discover” after 1989.

The generation of „Husak’s children“ was born in Czechoslovakia from 1974 to 1979. It is a term for a generation born in a strong population wave in the early 1970s. The name of this generation is derived from the then head of state, President Gustáv Husák. „Husak’s Children“ (The only systematic research of this generation was done by TNS Slovakia Lifestyle) are a generation that lived part of their lives in the socialist normalization period, experienced the revolution in 1989 and subsequently took advantage of the opportunities offered by its acquired freedom. It shows some common features of the ‘Y’ generation, but it also has indisputable differences, as members of that generation grew up in different conditions and was shaped by different possibilities and values. Members of this generation were formed to live their lives according to a certain, prescribed order. In accordance with the consensus, it was necessary to complete school, get education, get employed, start a family, get a living.

It is not easy to grasp the characteristics of the Generation of „Millennials“ because it is not exactly given who is in this generation. They are mostly members of the „Y“ generation and, to a lesser extent, the „Z“ generation. They are people born between 1980 and 1999, but it is a generation that deviates slightly from the classic characteristics of the ‘Y’ and ‘Z’ generations (Cheung 2007, whats.techtarget 2018). Millennials, as members of their generation, have an unflattering reputation among employers and companies. They are often dissatisfied with their job, trying to promote changes in the workplace regardless of their boss’s opinions, requiring employers to give them bonuses and benefits, usually in form of more holiday and freedom, flexible working hours or home office. Their desire for freedom and independence also manifests itself outside work, in a home environment, and in contact with friends (Howe and Strauss 2009). Millenials are individualists who have problems with authorities.

Unfortunately, it is not yet possible to gather comparable information for Generation of „Snowflakes“, and unfortunately there were not many members in our research. It is a generation that follows the generation of „Millennials“ since they were born after 2001. The term „snowflakes“ refers to babies wrapped in cotton, saying that these children are spoiled. It is a generation which name refers to originality and individuality, as each snowflake is unique and unrepeatable. Representatives of this generation have been described by some authors as overly sensitive and self-centered (Davis 2012), but this is nothing special because of their age, as members of this generation are still, usually, schoolchildren. It is openly said this generation is a generation of rebels, which is spoiled, not satisfied with anything, and these people criticize everything. In a way, however, these characteristics are applicable to all young people, so it is not yet possible to consider this generation as profiled. However, trying to grasp the „snowflake“ preferences is very important for companies. They are beginning to realize that this new generation may not want to do what previous generations will have other preferences and wishes. The generation of ‘snowflakes’ will surely be affected by ongoing climate change, with a very intensive focus on environmental issues. It has grown up with technology and often, this generation is forecasted to solve the civilization problems (note [1]).

Research results

The marketing survey, described in this section, was conducted in the Slovak Republic, from September 25, 2019 to October 13, 2019. The number of respondents was 545 of which 243 were men and 304 women from all regions of Slovakia. However, the research sample of the snowflake generation was so small that the inclusion in the charts of this generation does not have the required informative value but has an informative value, therefore this generation is also represented in the graphs. Respondents identified themselves with individual generations as described in the theoretical part.

The research was of a commercial nature and was conducted in accordance with the objectives of the VEGA 1/0737/20 grant project called Consumer Literacy and Changes in Consumer Preferences when Buying Slovak Products. Its main objective was to monitor consumer preferences within the generations of Slovak consumers. The answers to those questions about consumers’ environmental responsibility and their preferences in the context of designing marketing strategies were included in this paper. We focused on the attitudes of Slovak consumers to product recycling, preferences of Slovak products as a tool for shortening the supply chain and placing bio-production on the Slovak market of consumers of different generations. The aim was to identify how customers of different generations behave within the framework of sustainability for the needs of a client who produces organic food, but has not yet promoted or encouraged them to communicate this to customers, which in practice would mean changing the sales model and increasing the number of sellers.

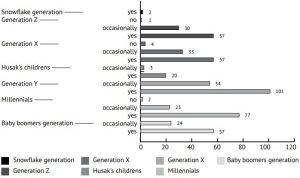

Figure 1: Which generation are you? / Do you recycle?

Source: Authors

The aim of this question was to find out how respondents feel about recycling. Occasionally, in Slovakia, the response „I recycle occasionally” may also mean that containers for recycled waste are unavailable. The question of recycling was included in the research mainly because the research sponsor wanted to examine the level of environmental responsibility and, rightly, the recycling rate is an indicator of it. The highest rate of recycling was shown in the members of the generation Y, which is clear from the graph. However, it is surprising that members of the Z generation are at a very similar level to the X generation and baby boomers. The answer „no, I do not recycle”, is extremely rare, therefore we can state that members of all generations see recycling as a necessity.

The issue of recycling, in a different context, is also addressed by the introduction of fully recyclable packaging. Y and Z generations are the ones who perceive the need to change the packaging of products and reduce their volume or type. It can be assumed that in the future they will mainly buy products that can be packed in returnable or fully recyclable packaging. It is gratifying that even generations of previously born would accept the policy of returnable packaging, which is only being discussed in Slovakia but the legislation does not yet cover it. This is illustrated in the following figure.

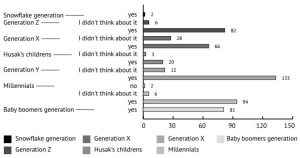

Figure 2: Which generation are you?/ Would you accept a policy of returnable or fully recyclable packaging?

Source: Authors

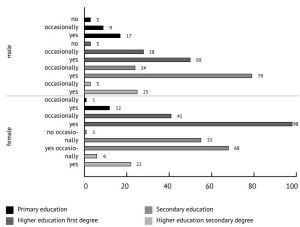

In relation to the educational level, it was assumed that people with the lowest education would be the most indifferent to recycling issues, and those with the highest education would have the most information on sustainability issues, and they would be those responsible for the environment. In principle, this assumption has been confirmed in the research and research has shown that this is true from the first, bachelor’s degree. Research has also shown that women are by one third more responsible than men in recycling.

Figure 3: Do you recycle? / Gender/ Education level

Source: Authors

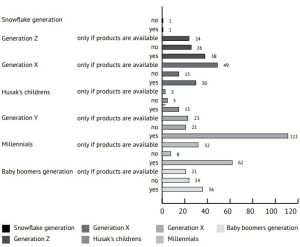

The issue of shortening the supply chain, although only indirectly linked to the promotion of domestic products, as we tried to prove within the theoretical part, is a relatively complex problem, which also involves the questions of marketing communication and ethnocentrism. In spite of possible doubts, in Slovakia the support of ethnocentrism has proved to be one of the most viable ways to support domestic production and shorten the supply chain, thus affecting the carbon footprint of products. Products manufactured or grown in accordance with sustainability principles are most desirable in the Y generation, which seems to be the most knowledgeable and responsible in the context of the issue. At the same time, it seems that its representatives are those who have sufficient information about the products, they are interested in where the goods are produced, the quality of the goods and if these goods can be purchased directly from producers. Given the fact that it is an economically active generation, the higher price of domestic products does not matter. Generation Y is also the one that, most likely, will affect the preferences of the Z generation, and the Millennials consequently Therefore, it is very likely that the trend of preference for domestic products produced or grown in accordance with sustainability principles will be strong.

Figure 4: Which generation are you? / Do you prefer organic products grown or produced in Slovakia?

Source: Authors

Conclusion

To sum up the results of the research, we could clearly state that environmental responsibility is gradually being promoted by the consumers of Slovakia. The preferences of customers across all generations are changing significantly, although preference changes do not occur evenly across generations. Early generations that have been researched are changing their purchasing behavior and changing their purchase preferences. Customers learn and have the opportunity to obtain information, prefer products that they can clearly identify, and prefer those that are produced or grown in accordance with sustainability principles and their production is as environmentally friendly as possible. The environmental criteria of the European Union and the pressure to further tighten them create space for the legislation of individual EU countries. The pressure to tighten environmental criteria, which leads not only to the improvement of product quality but also to the direction of carbon-free production. The change in customer preferences is also evident based on our research. Customers welcome increasing pressure on businesses, as well as retailers, to develop marketing strategies that reflect customer wishes and build on one of their competitive advantages according to sustainability principles. Customers who do not currently take environmental criteria into consideration when purchasing and consuming products are gradually declining in all generations examined by us. Marketing strategies based on sustainability must therefore be developed by all businesses, not just those that have already implemented environmental objectives in their goals. Over the next 10 years, sustainability principles will become the standard and selling products with no environmental criteria will be literally impossible. The absence of any sustainability criterion, whether it belongs to those we have mentioned or will be drafted as new, is a mistake in the marketing strategy that a company can pay for by the loss of customers.

Poznámky/Notes

[1] Given that members of the „Alpha“ generation could not be included in the survey, we will not present the characteristics of this generation.

The research was of a commercial nature and was conducted in accordance with the objectives of the VEGA 1/0737/20 grant project called Consumer Literacy and Changes in Consumer Preferences when Buying Slovak Products.

Literatúra/List of References

- Kotler, P. and Armstrong, G., 2004. Principles of marketing. Upper Saddle River: Pearson Education, 2004. ISBN 0131018612.

- Meadows, D. H., Meadows, D. L. and Randers, J., 2012. Limits to growth the 30-year update. Earthscan, 2012. ISBN 1849775869.

- William, W. and Wimsatt, A., 1997. Environmental marketing. Strategies, practice, theory and research. (Ed. By Polonsky, M. J. and Mintu-Wimsatt, A. T), NY: The Haworth, Routledge, 1997, p. 180-210. ISBN 978-1560249283.

- Jonas, H., 1989. Princzip Verantwortung: Versuch einer Ethik für die technologische Zivilisation. Suhrkamp, 1989. ISBN 978-3518220054.

- Torres, N. H. J. and Gutiérrez, S., 2007. The purchase of foreign products: The role of firm’s country-of-origin reputation, consumer ethnocentrism, animosity and trust. 2007. [online]. [cit. 2013-1¬0-09]. Available at: <http://gredos.usal.es/jspui/bitstream/10366/75189/1/DAEE_13_07_Purcching.pdf>

- Hill, R., 2002. Managing across generations in 21st Century: Important lessons from the Ivory Trenches. In: Journal of Management Enquiry. 2002, 11(1), 60-72. ISSN 1056-4926.

- Bergh, J. and Behrer, M., 2015. How cool brands stay hot: Branding to generation Y. Kogan Page, 2015, p. 210-219. ISBN 978-0749476007.

- Smolka, S., 2019. Charakteristika generácií slovenských spotrebiteľov. In: Marketing Science & Inspirations. 2019, 14(1), 2-11. ISSN 1338-7944.

- Cheung, E., 2007. Baby boomers, generation X and social cycles. USA: Longwave Press, 2007, p. 88. ISBN 9781896330068.

- whatis.techtarget, 2018. Millennials (generation Y). 2018. [online]. [cit. 2019-02-13]. Available at: <https://whatis.techtarget.com/definition/millennials-millennial-generation>

- Howe, N. and Strauss, W., 2009. Millennials rising: The next great generation. New York: Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, 2009, p. 54. ISBN 9780307557940.

- Davis, E.: Fundraising and the next generation: Tools for engaging the next generation of philanthropists. John Wiley & Sons, 2012, p. 8-22. ISBN 9781118236574.

Kľúčové slová/Key words

consumer generations, customer preferences, sustainability, marketing strategy, ethnocentrism, recycling

generácie spotrebiteľov, preferencie zákazníkov, udržateľnosť, marketingová stratégia, etnocentrizmus, recykláciaJEL klasifikácia/JEL Classification

M31

Résumé

Udržateľnosť ako faktor meniacich sa marketingových stratégií na základe preferencií zákazníkov v kontexte rôznych generácií na Slovensku

Najaktuálnejšou výzvou moderného marketingu je potreba začleniť princípy udržateľnosti do marketingových stratégií. Presadzovanie princípov udržateľnosti si vyžaduje stanovenie environmentálnych cieľov na úrovni podniku a navrhnutie marketingových stratégií, ktoré spĺňajú environmentálne požiadavky a preferencie zákazníkov. Článok sa venuje dvom základným témam, problematike environmentálneho marketingu na pozadí zákazníckych preferencií a generácií spotrebiteľov, presnejšie tak, ako sa profilovali na Slovensku. Cieľom skúmania preferencií zákazníkov rôznych generácií bolo dokázať, že implementácia princípov environmentálneho marketingu je nevyhnutná. Hoci cieľom výskumu bolo korelovať vybrané zistenia s preferenciami environmentálnych cieľov rôznych generácií, výskum zameraný na správanie rôznych generácií spotrebiteľov v rámci konceptu udržateľnosti odhalil niektoré originálne zistenia týkajúce sa hodnotenia etnocentrizmu v rámci koncepcie udržateľnosti.

Recenzované/Reviewed

6. September 2021 / 18. September 2021