The textile business is an excellent example for permanent transformations of the life-style of consumers. The first cycle in the Darwinism of the European textile sector was dominated by traders ‘knowledge about the sources of the product-materials and opportunities for processing. In a second phase covering the start of industrial mass-production and professional mass-distribution outlets for textiles were established with benchmarks at high frequency spots in down-towns of agglomerations like Berlin, Cologne, London or Paris. Department stores became the anchor of cities and for life-style driven citizens. In the third phasis the outlet-dominance is attacked by IT-driven businesses by the development of tools like the European Article Numbering-system, chips and QR-codes, clouds for big data and data-mining, artificial intelligence and virtual reality. For the textile traders it is an improvement of the efficiency by the ability to control the total supply chain electronically; for the consumer the potential interconnectivity with the internet and smartphones is an empowerment of demand because the choices for alternative points of sales are permanently increasing and mobile shopping decreases the dependance on locations of brick-and stone. Of course, this is resulting in big changes for the supply patterns.

Innovation of businesses

The innovation of businesses is a permanent process initiated by thousands of individual decisions either to cut costs or to increase sales volume by product adaption. Academic pioneers to analyze empirical data about those processes are Kondratieff (1926) for macro-economics and Schumpeter (1961) for micro-economics. Innovation cycles in retail/wholesale as a sector-analysis has been systematically documented firstly by Hallier (1999a, 1999b, 2022a) based on reports about sub-groups of this spectrum (Hahn 1984; Hauptmann 1892; Birchall 1997; Bauer et al. 1999b, p. 162-174; Zola 2004; Hallier 2002, p. 155; Hallier 2002, p. 210-212; Bauer et al. 1999b, p. 185-186; Bauer et al. 1999b, p. 176-180; Bauer et al. 1999b, p. 180-192) or own observations.

| – Steam Engine | – Railways | – Electrical Engeneering | – Petrochemical Industry | – Information Technology | – Lithium Industry |

| – Cotton | – Steel Production | – Chemestry | – Automobiles | – Global Trade | – Smart Economics |

| 1800 | 1850 | 1900 | 1950 | 2000 | 2050 |

| – imperial import / export | – local consumes cooperatives | – first national buying groups | – supermarkets | – RFID | – data-clouds |

| – domestic commerce | – start of department houses | – start of mail-order companies | – big boxes | – internet B2B/B2C | – block-chain technology |

| – shopping centers | – omni-Channel | – internet of things | |||

| – information technology | – mobile shopping | – artificial inteligence | |||

| – mobile shopping | – retail knowledge consortia |

Table 1: The impact of innovations for the entrepreneurs

Source: Hallier (2020)

The impact of innovations for the entrepreneurs and the changes of consumerism within the centuries as well as a prognosis of the future within the next decades can be summarized for example by the sub-group Textile Trade. Starting in the 20ies of this century shopping in an affluent society is mixing with entertainment: in future also inclusive gaming in a virtual world with avatars being sponsored by the branded goods industry of textiles or by outlet-chains. The final outfit of customers might be co-determined by long-distance partners in those games or it might be a decision tool for the planning of a meeting of a group of shoppers in a specific outlet at a certain date. The real world and the virtual world mix in a Metaverse.

Origins of textile trade

Tracing family businesses in the textile sector one impressive example from the Middle Ages is the Fugger Clan from the city of Augsburg/Germany (Hallier 2002, p. 12 ff). The family was named by the Latin word „fucare“ standing for the technical process to create from neutral cotton the basis for colored clothes. The Fugger brothers Hans and Ulin started in 1367 and 1377 their businesses in Augsburg: importing cotton from Egypt via Venice/today Italy, transporting the cotton over the Alpes-mountain-range and coloring the stuff in cooperation with small local manufacturers. The next Fugger generation expanded the internationalization to cover also the East of Europe and the Baltic Sea. Additionally, they started to diversify into the metal business (mining gold/silver) in Austria and Hungary – finally also banking mainly for the Pope but also for Cesar Maximilian and Cesar Karl V.

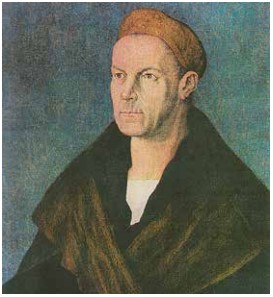

In 1517 like Cesar Maximilian also Jakob II Fugger ordered a portrait painted by Albrecht Dürer (Hallier 2002, p. 15) – while Ulrich II Fugger asked Hans Holbein the Older to draw him. The paintings and the outfit of the aristocrats and the traders are documents for the desire of emancipation between the upper classes – also seen in detailed regulations for dress-codes by the Augsburg Administration in 1537, 1551 and 1581.

Figure 1: Fugger

Source: Hallier (2002, p. 15)

Figure 2: de Respaigne

Source: Hallier (2002, p. 259)

„Dressing for Image“ could be called also a portrait of the trader Niclas de Respaigne from Amsterdam who had moved his business from Venice to the textile center of the Middle East of that time Aleppo (Turkey/Syria). Peter Paul Rubens painted him in 1619 when de Respaigne was getting to marry (Hallier 2002, p. 259). He was painted dressed in the Oriental (Ottoman-/Turkish) Style standing on an Anatolian carpet. Cloth styles and accessories grew in importance.

Start of mass-distribution

A new epoch started with the discovery of America and the import of cotton from there. In response to increased demand on the one hand side and new sources for import on the other side: the painting of Rembrandt van Reijn in 1662 is titled „Quality Control“ and shoves the Guilt of the Amsterdam Textile Traders checking the quality of their imports (Hallier 2002, p. 255).

Figure 3: Amsterdam Merchants

Source: Hallier (2002, p. 255)

This trend of mass-distribution of textiles is also taken as a topic by the French impressionist Edgar Degas who visited parts of his family who lived in New Orleans/USA earning their livings in the textile business (Bauer 1999b, p. 129 f). His painting „Office of a cotton-trader in New Orleans“ in 1873 has to be connected with his letters reporting about his stay in the USA comparing it with Paris in France: „All day we speak about cotton and credits; the ships from Europe to fetch the cotton-exports are coming in a frequency like the buses at the Paris-station“! The global supply chain and the importance of capital for increased markets became of big importance for the textile business.

Figure 4: Degas-family

Source: (Bauer 1999b, p. 130)

That century had another impact on the textile industry also in macro-economics in general: it was the start of exhibitions about the beginning epoch of industrialization. In 1811 for example the city of Düsseldorf/Germany prepared an exhibition for the French Cesar Napoleon I. to demonstrate the potential of the occupied Rhineland-area. It was several times repeated and was one of the origins to organize later EXPOs for the „jet-set“ society of that time which travelled by the new cross-border railway-systems to explore the life-style of other countries (Hallier 2022b). In Paris Gustave Eiffel designed for the Paris Expo the famous tower which was planned to stay only for the period of the exhibition – but actually became the landmark of the city of Paris till today. Other places like Milano in Italy are also still „bundler“ of all local/national producers of the textile sector to exhibit the latest fashion of Italy. In Germany after World War II Düsseldorf took over this function from the divided capital Berlin – but lost its unique sales position in West Germany after the reunification of Germany after 1990 when Berlin started to be again the number 1 trend-setter of life-style. Fashion Today reported in its News of KW 27/2022 that the Berlin exhibitions Premium, Seek and The Ground had invited also 25 international buying directors to arrange proactively meetings with the exhibitors (Fashion Today 2022). Further they announced that in 2023 the events of the Premium Group would be organized parallel to the Berlin Fashion Week. The business-competence of textile traders was for more than a century linked to those hot-spots where designers, producers, models, high-level distributors and the high society were meeting like in circus-events watched by the public.

Important to mention that it was also Gustave Eifel who designed the fashion-show-room Au Bon Marche: a department-store with a sales-area of 25.000 square-meters – described by the French writer Emile Zola in his famous „Paradise for Ladies“ (Zola 2004) – which was showing the social impact also for the small businesses which started to be eliminated by the big players. Paris was competing in the ranking of consumers of the upper classes with London, Cologne, Berlin and Moscow, in 1902 Tietz in Cologne (today Kaufhof) was quoted to state that his sales-people were able to serve customers in 8 languages (Hallier 2002, p. 155). Interestingly in Germany all the big department-stores started with textiles and only later diversified by an enlargement of the assortment.

Others like C&A, P&C (with their tradition to trade textiles in the triangle Belgium, Netherlands and Germany) or many local players remained in the textile sector for partly for more than two centuries: others like H&M or Zara joined in an international expansion drive but being focused on special target groups. Lately in Germany for cheap offers special textile discounters like Takko or Kik followed in down-town locations which became as outlets too small for food-stores like modern supermarkets or which are placed especially in low-income areas. Last but not least food-discounters like ALDI or Lidl as well as coffee-shops like Tchibo use textiles for weekly offers to get a higher frequency to their shops or to cash-in with additional assortments from those customers which can be reached by on-the-spot offers. As a result of those promotions the food-discounter ALDI is within the Top 10 textile retailers in Germany and the coffee-shop Tchibo has pushed the special offers to over 50 percent of its total turnover.

For labels the alternatives are high-level flagship-stores to promote the brand within an umbrella-strategy and to offer in factory outlet centers (FOC) a limited assortment which is on average 15 percent lower in its sales-prices and is additionally run by slogans like „over run“, „factory seconds“, „damaged“, „past season“, „samples“ or „discontinued items“. Very often those factory outlets are in agglomerations of at least five label-producers with a minimum of 4500 square-meters sales area (Hallier 1999c).

This evolution of the mix of target-groups enlarged also the potential tools of marketing: the store-format, its target- group’s financial situation, its range of assortment, the presentation-style became equally important like the product itself. One example of the latest trend to catch the eye and the heart of upper- level consumers is the new store of the French top-designer Christian Dior in Paris who in 2022 upgraded his store by adding to the sales-floor also three gardens, one restaurant, one cafe and one patisserie. Another example is in Berlin P&C opening its first Mega Eco Store responding by this with a Corporate Social Responsibility strategy to the trend of many people in Germany to go shopping in stores which are constructed according to environmental aspects, presenting products which fit ecological standards and which are produced under fair conditions and transported with a low footprint (Kölner Stadt-Anzeiger 2022). The business became more complex – more and other abilities were needed beside the product-knowledge.

This increasing spectrum for retailers has also an impact on exhibitions: in this context it has to be remembered that it had been fairs like the EXPO in Paris which became the mirrors of the latest life-styles. After World War II there had been two competing trends : the revitalization of traditional department stores with beautiful decorated windows – and on the other hand the American Way of Life by modern sales technologies (Hallier 2022b). Both trends for better sales was the idea to launch the exhibition EuroShop and still is the basis of the success of the world-leading triannual shopfitting exhibition in Düsseldorf which was started in 1966 by the same fair-management which was responsible for the fashion shows of IGEDO, which was the show-room of West Germany for fashion. The flagship of shopfitting EuroShop again reacted in 1997 to follow the latest consumer trends by segmenting its IT-shows under the name of EuroCIS and to exhibit annually for this target-group of IT-managers in retail/wholesale also to follow the speed of technical/digital innovation in this segment.

From big boxes to big data

Especially since the middle of the 70ies the growth of the big players was supported by innovations in the IT-Sector (Hallier 1987; Heidel 1990; EHI 1994; Hallier 1995, Hallier 1999d). Only by the electronic control of the articles in the shelf of the outlets or the delivery systems the efficiency of big groups of outlets could/can be checked. Due to the multiplication of outlets per chain the single outlets could be no longer visited permanently by the owner of the businesses or by Board-members but had to be delegated and to be controlled by new technology.

As an example, for the innovation of the key-elements of the retail technology is the EAN-barcode which was introduced in 1975. It contains the country of origin, the manufacturer and the product. By this the inventory within the depots and the stores could be quickly followed up. Actually, the POINT of MANAGEMENT DECISION (PMD) could be turned from the head of a manager in the headquarter of a company towards the POINT of DATA COLLECTION (PDC). Benetton for example changed the production of its cloths no longer in connection to spring/summer/autumn/winter trade fairs/collections but permanently due to the incoming data from the cash-zones of its outlets.

At about the year 2000 the printed barcode was replaced step by step by the chip technology which was able to integrate more data than the printed version and enabled interconnectivity with other systems without manual intervention. Machines started to take over from human beings: AI (Automated Intelligence) became the key-word. The UK retailer Morrisons is quoted at EuroCIS 2022 to cover already more than 90 percent of its product movements by AI of their IT provider Blue Yonder. The French department store Bonprix claimed at the same event to have survived well the decreased sales caused by the Covid Crisis due to AI software which had speeded up the data mining.

Other advantages of the chip-technology and its connectivity with data clouds is the Internet of Things (IoT): the capacity allows to demonstrate details for the application of the bought products and to attach marketing communication. Last but not least the QR-code (Quick Response) allows the consumer to read advertising in different media and to order by a photo of the code the product immediately (Hallier 2011, p.148 ff).

The role of a wholesaler for the physical flow of products could change to be B2B – or even B2C-platform providers in the virtual world and deliveries will come increasingly by a delivery-partner with sub-partners. The definition „institutional wholesaler/retailer“ will show less members than the „functional wholesaler/retailer“. There will be a great boom in segmentation, diversification and partnering. One example of such recent cooperation is C & A Germany which started in July 2022 to place selective items at the German Site Amazon.de: the launch at the Dutch, the French, the Italian and the Spanish Sites are planned to follow.

The importance of data could be seen already after World War I when department houses were destroyed and the lack of capital did not allow new brick-and-stone outlets. In Nürnberg/Germany the Schickedanz family started a mail-order system based on the send-out of catalogues and data of customers (Hallier 2002, p. 210 ff); his company Quelle (the German word for „Source“) became a benchmark for success and was copied by others like OTTO after World War II. (Hallier 2002, p. 112 f).

Modern IT/digitalization became the competitor for the printed catalogues and the brick-and-stone outlets. Parallel to EuroShop 2008 in Germany the fashion online supplier Zalando was founded. In 2022 it has 35 million customers within 17 countries in Europe. Per minute 7500 online-orders are registered. This success of course is stimulating not only newcomers but also traditional business to react with omni-channel strategies – selling instore as well as online trying to push each channel by the visibility or the comfort of the other.

But even industry is involved in the search for direct contacts with the consumer. In summer 2022 for example Beiersdorf is promoting its range of sun-creams and beauty-articles by in-store activities with trade partners in Germany. Consumers are offered a free-of-charge bathing towel if they send in a cash-slip of having bought Beiersdorf products in the value of 20.- Euro (plus) to the address of the company. Of course, also the address of the shopper has to be sent for the mailing of the towel-parcel. The fabrics in this case of course are no sales-items but calculated as part of the promotion costs.

The latest trend comes via Virtual Reality (VR) and will be included in a Metaverse. Within interactive games avatars will have the image of the player/players. The play-background can be the image of outlets combined with images of products. Within the game the player and co-players can dress alternatively the avatar and those being in the players ‘team can decide together the final outfit or meet based on those discussions in a real store of that fashion supplier. Those games could be developed and promoted by producers or retailers or in cooperation between those two groups. It might be also seen as a potential new income for those who keep the owner-rights of those income. In the end of this thought, it might happen that the products‘ profit might be Zero – and the economic gain is the profit by advertising within the games as a kind of „listing price for the product“ or selling the data of the trends as a service of market research – similarly like in the Beiersdorf case-study.

Conclusion

The traditional textile trader as a specialist making decisions alone by creating ideas just in his head will no longer be able to execute all processing in mass-distribution. He will remain as a potential pioneer in niche-markets. Big business needs a broad knowledge of different abilities no longer capable by single persons or people with experience in one sector only.

Looking beyond the sector of textile-business one can see that companies like AMAZON or ALIBABA but also data-collectors like Google / Microsoft or DHL delivery start to act as partners within Retail Knowledge Consortia (Hallier 2022c). The future success will depend on the way leaders of companies will be able to bridge different company cultures for united ambitions.

And finally, it has to be realized that the traditional split of profit along the Total Supply Chain will switch from production and trade towards companies with data-competences /digital marketing experiences – even like game-developers. In macro-economic terms this will create big problems for developing countries if they do not have the skills or digital connections to participate with a fair share in the value-chain but if they remain just in the competition of offering the cheapest labour internationally (Hallier 2022d; Hallier 2022e).

Literatúra/List of References

- Bauer, H. J. and Hallier, B., 1999b. Kultur und Geschichte des Handels. Cologne: EHI-EuroHandelsinst, 1999. ISBN 3-87257-228-8.

- Birchall, J., 1997. The international co-operative movement. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1997. ISBN 9780719048241.

- EHI, Scannersysteme – Neue Impulse für Organisation und Marketing. Cologne: EHI, 1994. ISBN 3-87257-166-4.

- Fashion Today, KW 27/2022. [online]. [cit. 2022-8-20]. Available at: <www.fashiontoday.de>

- Hahn, H. W., 1984. Geschichte des Deutschen Zollvereins. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1984. ISBN 3525335008.

- Hallier, B., 1987. Sich ins Regal hineinrechnen. In: Absatzwirtschaft. 1987, 10. ISSN 0001-3374.

- Hallier, B., 1995. Der Handel auf dem Weg zur Marketingführerschaft. In: Absatzwirtschaft. 1995, 3. ISSN 0001-3374.

- Hallier, B., 1999a. In: Bauer, H. J. and Hallier, B., Kultur und Geschichte des Handels. Cologne: EHI-EuroHandelsinst, 1999, p. 260-263. ISBN 3-87257-228-8.

- Hallier, B., 1999c. In: EHI, Factory-outlet-center, Cologne, 1999.

- Hallier, B., 1999d. Wird ECR zum Club der Großen? In: von der Heydt, A., Handbuch efficient consumer response. Munich: Vahlen, 1999. ISSN 9783800622795.

- Hallier, B., 2002. Sammler, Stifter und Mäzene, p.155, Cologne: EHI Retail Institute, 2002. ISBN 3-87257-249-0.

- Hallier, B., 2011. Smartphones and QR-Codes. In: Hallier, B., Von der Krise zur Kompetenz/From Crisis to Competence, Bonn, 2011, p.148 ff. ISBN 978-3941502093.

- Hallier, B., 2020. News: Asian Century. 2020. [online]. [cit. 2020-12-24]. Available at: <www.european-retail-academy.org>

- Hallier, B., 2022a. 50 years perspective. 2022. [online]. [cit. 2022-5-30]. Available at: <www.european-retail-academy.org>

- Hallier, B., 2022b. Promoting life-style. 2022. [online]. [cit. 2022-8-20]. Available at: <www.european-retail-academy.org>

- Hallier, B., 2022c. Empowered logistics. 2022. [online]. [cit. 2022-1-30]. Available at: <www.european-retail-academy.org>

- Hallier, B., 2022d. Darwinism in the textile sector. 2022. [online]. [cit. 2022-6-30]. Available at: <www.european-retail-academy.org>

- Hallier, B., 2022e. Accelleration by disruption. 2022. [online]. [cit. 2022-8-31]. Available at: <www.european-retail-academy.org>

- Hauptmann, G., 1892. Die Weber. Berlin, 1892.

- Heidel, B., 1990. Scannerdaten im Einzelhandelsmarketing. Wiesbaden: Springer Fachmedien, 1990. ISBN 978-3-409-13649-5.

- Kölner Stadt-Anzeiger, 2022. Mode ohne schlechtes Gewissen, 12. 8. 2022.

- Kontratieff, N., 1926. Die langen Wellen der Konjunktur. In.: Archiv für Sozialwissenschaft und Sozialpolitik. 1926, 56, 573-609. ISSN 0174-819X.

- Schumpeter, J., 1961. Konjunkturzyklen. Eine theoretische, historische Analyse des kapitalistischen Prozesses. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck, 1961.

- Zola, E., 2004. Das Paradies der Damen. Frankfurt: Fischer Taschenbuch Verlag, 2004.

Kľúčové slová/Key words

innovation cycles, mass distribution, life-style, IT-platforms, data mining, artificial intelligence, retail knowledge consortia, value-chains, avatars, metaverse

inovačné cykly, masová distribúcia, životný štýl, IT platformy, data mining, umelá inteligencia, maloobchodné znalostné konzorciá, hodnotové reťazce, avatary, metaverse

JEL klasifikácia/JEL Classification

M31

Résumé

Obchod v transformácii: Príklad textilného priemyslu ako inovátora mestského životného štýlu

Textilný priemysel je výborným príkladom pre trvalé premeny životného štýlu spotrebiteľov. V prvom cykle Darvinizmu v európskom textilnom sektore dominovali obchodníci s „vedomosťami o zdrojoch produktov-materiálov a možnostiach spracovania“. V druhej fáze, ktorá zahŕňa začiatok priemyselnej hromadnej výroby a profesionálne masové distribučné predajne textilu, boli zriadené referenčné hodnoty na vysoko navštevovaných miestach v centrách aglomerácií ako Berlín, Kolín nad Rýnom, Londýn alebo Paríž. Obchodné domy sa stali kotvou miest pre občanov orientovaných na životný štýl. V tretej fáze útočia na dominanciu outletu firmy riadené IT vývojom nástrojov, ako je európsky systém číslovania kódov (EAN), čipy a QR kódy, cloudové riešenia pre veľké dáta a data-mining dát, umelá inteligencia a virtuálna realita. Pre obchodníkov s textilom je to zlepšenie efektivity vďaka možnosti elektronickej kontroly celého dodávateľského reťazca; pre spotrebiteľa je potenciálne prepojenie s internetom a smartfónmi posilnením dopytu, pretože výber alternatívnych predajných miest neustále rastie a mobilné nakupovanie znižuje závislosť od umiestnenia kamenných predajní. To má, samozrejme, za následok veľké zmeny v podnikateľských modeloch na strane ponuky.

Recenzované/Reviewed

25. September 2022 / 29. September 2022