Attracting and retaining talented employees has become one of the most pressing challenges for companies in their struggle for achieving and sustaining competitive advantage. Personnel assessment and personnel selection plays an important role in this context. On the one hand, its methods can help, to distinguish between suitable applicants and less suitable ones. On the other hand, personnel assessment and selection affects the perceived attractiveness of the employer. Therefore, it is closely related to employer branding.

In the course of digitization, artificial intelligence is now increasingly used in personnel attraction and selection. New instruments are being introduced. For example, computer-aided speech recognition can allegedly be used to generate personality profiles of applicants. However, the scientific debate on this topic seems to lag far behind the marketing of corresponding instruments. From a scientific point of view, it is questionable not only whether such instruments are prognostically valid, but also whether they are accepted by applicants.

Within the framework of an experimental study, two important questions are thus investigated: What effect do job advertisements have on the perceived attractiveness of an employer if the use of computer-aided speech recognition for personnel selection is explicitly pointed out? To what extent is the relationship between job advertisements with and without reference to speech recognition on the attractiveness of employers moderated by technology acceptance, country-specific differences and qualification? Answers to these questions will enhance our understanding of applicant reactions to selection procedures. In addition, they provide important information for the practice of human resource management in the context of employer branding.

Introduction

It is well known that nowadays the competitiveness of companies is significantly depending on the availability of qualified personnel. In particular, there is currently a high demand for people with experience and skills in IT and related fields who deal with artificial intelligence (AI). According to various studies, AI will have a significant impact on the professional world. At the same time the demands on professions and their nature are changing. Some might even disappear in the future due to the use of AI, many will change, and completely new professions will emerge (Wilson, Daugherty and Morini-Bianzino 2017). The exact extent of the change initiated by AI is not yet precisely predictable. The available analyses somet sometimes come to very different conclusions (Arntz, Gregory and Zierahn 2017; Frey and Osborne 2017). However, it can be assumed that those companies that make sensible use of AI will gain a considerable competitive advantage and those employees will enjoy a high level of employability who are able to work hand in hand with AI.

However, recruiting these people is not an easy task. Many organizations nowadays compete for this IT-affine target group. In addition, the target group is relatively small due to demographic factors on the one hand and the high level of qualification required on the other (Van Hoye and Lievens 2009). In order to be able to win this target group over, increased efforts in employer branding and recruiting are required.

The increasing use of AI can also be observed in recruiting and the selection of candidates. Various authors assume that the use of AI in recruiting and personnel selection will lead to more efficiency and quality for both companies and candidates (Upadhyay and Khandelwal 2018). Based on a literature review Albert (2019) identifies about a dozen fields where AI could be applied in the future. Despite this potential, his empirical study comes to the conclusion that currently only a few application fields actually exist, predominantly when it comes to chat bots, screening software and tools for task automation. Moreover, AI in recruiting is primarily used by rather larger, technology-oriented and/or innovative companies.

When it comes to applicant screening, one field of application for AI is computer-based testing as part of the personnel selection and assessment process. An example in this context is the so called PRECIRE JobFit, which is a personality test of the German company Precire Technologies. The test is designed to automatically record job-relevant characteristics using the voice sample of a 15-minute telephone interview. Although there are serious doubts about the prognostic validity of the test (Schmidt-Atzert, Künecke and Zimmermann 2019), numerous companies in Germany are said to already use it, including large international corporations (Precire Technologies 2020).

In view of the criticism of the to-be questioned prognostic validity, Precire and its customers have already reacted. In the future, the test is no longer to be used primarily for personnel selection. Instead, the test will be increasingly positioned as an employer branding instrument. By using AI, the message is to be communicated that the companies are innovative and use the latest technology. This is primarily intended to better address target groups with an affinity for technology. However, so far there are hardly any findings on whether the use of AI in the recruiting process has a positive effect on perceived employer attractiveness.

In light of the development outlined above, it must be assumed that AI will be increasingly used in recruiting and employer branding in the future, and companies that use AI may be better able to attract precisely those people who either already have the appropriate skills or at least show a high affinity for AI. However, so far there are hardly any scientific results available that empirically support the effect of AI on perceived employer attractiveness. This research gap shall be closed in the context of this article. In particular, the question is to be investigated to what extent perceived employer attractiveness is influenced when job advertisements explicitly state that AI-based tests such as automated speech recognition are applied in the recruitment and selection process. Furthermore, it shall be analyzed to what extent is the relationship between job advertisements with and without reference to such AI-based personality tests on employer attractiveness is moderated by applicants’ technology acceptance, nationality and qualification.

1 Employer attractiveness

Attracting and retaining the best talents has become a central concern of many companies due to a significantly increased shortage of skilled workers. Here, employer branding is seen as an effective strategy for gaining competitive advantage in the increasingly competitive labor markets (Barrow and Mosley 2011). To achieve this, it is important to position the company as an attractive employer. To this end, an employer brand must be created, which contributes to existing and future employees, perceiving the company as an „employer of choice“ (Ambler and Barrow 1996; Dabirian, Kietzmann and Diba 2017).

The core of the employer brand is the so-called employee value proposition (EVP). The EVP consists of a set of characteristics that determine the perceived attractiveness of an employer from the perspective of the respective target groups (Backhaus and Tikoo 2004). Therefore, the characteristics that are particularly driving the perceived employer attractiveness have been intensively investigated in the last couple of years. Lievens and Highhouse (2003) for instance conclude in a study of potential applicants in the banking sector that career opportunities, location considerations, the work itself, and salary are the best predictors of employer brand attractiveness. In another study, in which members of the Belgian armed forces are surveyed, Lievens (2007) concludes that job diversity, travel opportunities and opportunities for teamwork have a significant influence on employer attractiveness, but not promotion, salary and other benefits. In a similar study, Lievens, Van Hoye and Anseel (2007) show that applicants for the Belgian armed forces value structure, job security and sporting activities, but that travel, salary and promotion opportunities do not have a significant impact on employer attractiveness. Agrawal and Swaroop (2009), who examine the attractiveness of the employer brand in various industries in India, conclude that the work itself has a positive effect, as do the salary offered and location aspects. However, their research also shows that social or cultural factors, learning and promotion opportunities are not significant predictors of employer brand attractiveness. Indian final-year management students were also asked to examine employer attractiveness in a study conducted by Chhabra and Charma (2011). It was found that organizational culture, brand name and compensation were most preferred organizational attributes.

Although such studies shed first light on employer attractiveness, the results are quite heterogeneous and as such do not provide a clear picture. Furthermore, they do not indicate which of the characteristics are particularly relevant at which stage of the recruitment process. However, this is of crucial importance for the questions of this study, because job advertisements are typically relevant in early phases. In view of this, it can be helpful to take a closer look at the distinction between instrumental and symbolic attributes of organizational attractiveness.

Instrumental attributes refer to objective circumstances associated with working for a particular organization. Often these characteristics are linked to objective benefits, such as pay, training, working time and leave arrangements, or working conditions in general (Backhaus and Tikoo 2004; Van Hoye and Saks 2011; Van Hoye et al. 2013). For some instrumental attributes, such as performance-related pay, career opportunities and working conditions, there is evidence that they are relevant to potential applicants (Turban and Keon 1993; Van Hoye and Saks 2011; Van Hoye et al. 2013). However, they are usually less suitable for companies to differentiate themselves from competitors in the labor market. Many companies do not differ much in these respects (Lievens and Highhouse 2003).

Symbolic attributes represent the subjective meaning of belonging to an organization. Such attributes play a role particularly in the early phase of recruitment (Lievens and Highhouse 2003). Examples of symbolic attributes are prestige, integrity or innovativeness (Lievens and Highhouse 2003; Van Hoye and Saks 2011; Van Hoye et al. 2013). Such attributes are mostly abstract, less tangible, sometimes immaterial and have an emotional value. Symbolic meaning is created by people’s perception and the way in which conclusions about the organization are drawn from it (Lievens and Highhouse 2003; van Hoye and Saks 2011). Social identity theory (Tajfel 1978; Tajfel 1986) can be applied well in this context to examine the effect of symbolic attributes (Backhaus 2003; Love and Singh 2011). Such attributes can serve as a source of pride and are capable of increasing the self-esteem of an employee. They help employees to see themselves as part of a special social group (in-group) that is different from other groups (out-groups). This means that members of an organization define themselves by what their employer represents and derive psychological benefit from this (Highhouse, Thornbury and Little 2007). Symbolic attributes can therefore be better used in comparison with incremental attributes to differentiate themselves from competitors in the labor market and thereby attract applicants (Lievens and Highhouse 2003; Ployhart 2006; Highhouse, Thornbury and Little 2007).

2 Hypotheses development

2.1 Effect of AI-based personality test on employer attractiveness

AI is understood across industries as a key driver for innovation (Srinivasan 2014; Tsang et al. 2017). Innovation ability, in turn, is considered by many companies to be crucial for gaining competitive advantage (Yeung, Lai and Yee 2007; Azadegan and Dooley 2010). Therefore, it is of utmost importance for companies to have employees who can think and act innovatively.

Studies show that perceived organizational innovativeness can be an important decision criterion when choosing an employer (Sivertzen, Nilsen and Olafsen 2013). It is acknowledged that different people with different personalities have different preferences concerning their employers (Turban and Keon 1993; Backhaus and Tikoo 2004). Due to such personality differences, organizational innovativeness seems to be particularly relevant for those people, which have an innovative personality and therefore value an innovative working environment (Andreassen and Lanseng 2010; Cable and Turban 2001).

In order to be perceived as an innovative employer, the aspect of organizational innovativeness must be communicated through the use of appropriate communication channels. Traditionally companies have used offline methods, such as face-to-face communication and the distribution of print material. With the growing importance of the Internet, online instruments (e.g., company webpages, social media etc.) are increasingly used. When it comes to publishing job advertisements, these are primarily posted on the organization’s career website or job portals (Weitzel et al. 2018).

In the past, job advertisements have been treated as a recruiting tool only. Their scope of usage was predominantly on job requirements, not on presenting the organization as an attractive employer. Nowadays, however, it can be shown that organizations differentiate themselves much more from their competitors in the labor market if their job advertisements include elements of employer branding (Elving et al. 2013). On this basis, it can be argued that organizations should include innovative elements in their job advertisements if they want to attract innovative applicants. The use of AI-based personality tests can therefore help to ensure that organizations are perceived as innovative and therefore help to address innovative-minded people.

Based on these arguments, the following hypothesis is made:

Hypothesis 1: Companies posting job advertisements with reference to AI-based personality tests are considered more attractive than those that do not post such job advertisements.

2.2 Moderating effect of technology acceptance on employer attractiveness

People perceive new technologies in different ways (Bagozzi et al. 1992). For some people new technologies are complex and an element of uncertainty exist with respect to the adoption of them. People form attitudes towards new technologies prior to directly using them. Thus, actual usage may not be a direct consequence of attitudes when people are not convinced by them or feel even intimidated (Yoon Kin Tong 2009). On the other hand, some people are very open to innovations and feel attracted. Acceptance research, together with diffusion and adoption research, form the basis for explaining the behavior of users of technological innovations and factors influencing this process (Ginner 2018; Rogers 2010).

Acceptance research has its focus on the acceptance or rejection of an innovation (Quiring 2006; Ginner 2018). In recent years, there have been many different models developed to measure and predict user acceptance of new technology. Models have their roots in different disciplines such as IT, psychology or sociology (Venkatesh 2003). The most common models are „Theory of Reasoned Action“ (TRA) (Fishbein and Ajzen 1975), the „Technology Acceptance Model“ (TAM) and its modifications (Davis 1986; Davis 1989; Davis et al. 1989; Venkatesh and Davis 1996), „Theory of Planned Behavior“ (TPB) (Ajzen 1991), „Task Technology Fit Model“ (TTFM) (Goodhue and Thompson 1995), TAM2 (Venkatesh and Davis 2000), TAM3 (Venkatesh and Bala 2008) and Neyer, Felber and Gebhardt (2016). All of these models are competing and differ in key determinants for user acceptance.

To maintain innovation and competitiveness many companies must be attractive for job candidates. In this regard, companies with an innovative image might have an advantage as they appear more attractive to employees and job candidates especially to those with an innovative personality. So, within their corporate communication -especially HR communication- companies might use an organization’s innovativeness messages within their employer branding communication in order to attract high potentials. However, current literature remains scarce to provide empirical evidence on whether and how the communication of organizational innovativeness affects employer attractiveness (Sommer, Heidenreich and Handrich 2016).

As nowadays online recruiting has become a popular recruitment tool for many companies (Monavarian, Kashi and Raminmehr 2010) it is important to conduct further studies to get a better understanding of job candidates’ perception of new forms of technology and their influence on the employer brand. In this paper, our focus is on the effect of AI-enabled tools used during the recruitment process. We still know little about candidates’ perceptions to AI-enabled recruiting and the effect on employer attractiveness (Van der Esch and Black 2019).

There is some literature that reveals that people often use new technology for anticipated rewards such as innovation, novelty and fun (Davis, Bagozzi and Warshaw 1992; Mumford 2000). Applying for a job which uses AI-enabled technology for recruiting is relatively new. Based on an empirical study by Salge, Glackin and Polani (2014) we assume that job candidates could easily anticipate intrinsic rewards for engaging in an AI-enabled job application process. In conclusion, it is very likely that there is a difference in the perceived employer attractiveness, driven by the job applicant’s individual technology-acceptance within the recruitment process.

On the basis of this section, the following hypothesis is derived as follows:

Hypothesis 2: Technology acceptance differences influence the perceived employer attractiveness in relation to job advertisements with reference to AI-based personality tests.

2.3 Moderating effect of qualification’s technical proximity on employer attractiveness

In a recent academic study of Granić and Marangunić (2019) a literature overview in the educational context has been conducted. According to their findings, there is a respectable amount of literature about technology acceptance, stating the popularity of the TAM model itself in the overall field of technology acceptance models. Yet, there is a research gap in the examination of job applicants’ and graduates’ technology acceptance and its potential effect on employer attractiveness.

Another study within the U.S. education system about the implementation of online and blended education programs has been conducted by Arbaugh (2010). Here, differences between study programs have been found in the pace of acceptance of such innovative programs. The author states that online and blended business education programs have increased in all study disciplines during the last decade. Yet, faculty in information systems and management use these programs much more often than faculty in marketing and accounting. Moreover, these new forms of teaching are even less seldomly found in disciplines such as finance and economics. This means that students in different study programs have differently used new forms of teaching.

In a study among German universities Bührig, Guhr and Breitner (2011) investigated the use and technology acceptance of mobile applications of a university CMS system with respect to the enrolled study program. Students of technical and scientific study programs, such as engineering, computer sciences, or physics differed significantly from students enrolled in „philosophical“ study programs, e.g., humanities: In terms of technical equipment, 62% of students of technical courses possessed a smartphone whereas only 39% of humanities students possessed a smartphone. In addition, significant differences had been found as well in the use of these mobile devices. Students from technical and scientific courses of study were much more technophile. Furthermore, survey results among both groups revealed that students from technical courses felt more confident in using mobile devices. They used them more often, and tested new apps more frequently than students enrolled in humanities.

Although research about the qualification background and its influence on technology use and acceptance is still limited, we assume that there are differences between graduates from different disciplines. Based on these findings it can be concluded that the individual qualification background is a driver of technology acceptance. We further conclude that the „technical proximity“ of a qualification background enhances the technology acceptance of an individual. We assume that people with a technical or scientific background to be more technophile than people with a non-technical or scientific background do. With regards to section 3.1 we therefore assume, that those with a close „technical proximity“ qualification will be more attracted by technology-oriented/ innovative companies than those with a distant „technical proximity“ qualification. Hence, the qualification background of job applicants is likely to determine the technology acceptance within the recruitment process. In consequence, it will result in an effect on the employer attractiveness, if a job posting signals technology usage during the recruitment procedure, depending on the receiver’s qualification background, differentiated by the study program.

Based on this reasoning, the following hypothesis is derived:

Hypothesis 3: Qualification differences influence the perceived employer attractiveness in relation to job advertisements with reference to AI-based personality tests.

2.4 Moderating effect of country-specific differences on employer attractiveness

There is a growing awareness about the importance of national and intercultural differences when it comes to attracting and retaining employees (Sparrow 2009). The employer brand must be adapted accordingly so that employees in various countries feel addressed (Berthon, Ewing and Hah 2005). The fact that there are intercultural differences between countries in terms of perceived employer attractiveness has been empirically demonstrated by various studies in recent years. In a study conducted in sixteen European countries, Harzing (2004) found that graduates from Eastern European countries chose their employers because of value propositions and characteristics than differed to those graduates from other regions. Gowan (2004) as well as Berthon, Ewing and Hah (2005) found that differing nationalities and cultures had an influence on the perceived attractiveness of an employer brand. This applied to both existing and potential employees. Caligiuri et al. (2010) also note that in order to ensure employer attractiveness, it is important to consider culture-specific attributes. Alshathry et al. (2014) and Alnıaçık et al. (2014) come to a similar conclusion. They recommend that, due to national and cultural differences, employer brand communication should be adapted accordingly.

Despite intensive research, so far no findings seem to exist which empirically investigates the effect of AI on perceived employer attractiveness. However, research on technology acceptance shows that intercultural differences appear to be responsible for the fact that new technologies are accepted to varying degrees by users (Straub 1994; Straub, Keil and Brenner 1997; Hill et al. 1998; Veiga, Floyd and Dechant 2001; Olasina and Mutula 2015).

In addition, there is a rich literature stream on the culture-specific differences of developing innovations and adopting new technologies. Hofstede’s „dimensions of culture“ for example have been used to examine the differences between nations and cultures (Hofstede, 1980). Based on his 5-dimensions-framework (power distance, uncertainty avoidance, individualism, masculinity, long-term orientation) several studies have been conducted to analyze the technology/ innovation-orientation of countries (Hofstede 2001; Tekin and Tekdogan 2015). Characteristics like „uncertainty avoidance“ are used to test for technology acceptance, e.g., the higher a country’s uncertainty avoidance score, it is said the less likely people in that country are to adopt innovations. In a study conducted by van Everdingen and Waarts, empirical findings indicate that the extent of these dimensions have a significant influence on the country technology adoption. The authors for exemplary state, that overall, Nordic European countries are most receptive to breakthrough innovations. In comparison, countries characterized by a high level of uncertainty avoidance and a low level of long-term orientation (such as Mediterranean countries) are less likely to adopt such innovations (van Everdingen and Waarts 2003).

Accordingly, it can be assumed that national and intercultural differences also exist when it comes to the acceptance of AI-based personality tests. This in turn could have an effect on the perceived employer attractiveness of those organizations, which communicate the use of such tests in their job advertisements.

On the basis of this discussion, the following hypothesis is derived:

Hypothesis 4: Country-specific differences influence the perceived employer attractiveness in relation to job advertisements with reference to AI-based personality tests.

3 Methodology

3.1 Procedure and sample

Our sample consists of 203 graduates with an average age of 23.7 years (SD = 2.79). 59% of the participants were male. They are enrolled in business administration with a major in HRM or marketing or in a business information system program. Participants study in either Germany or Denmark. Breakdown by country and degree program are shown below in table 1. Data has been collected via an online questionnaire that had been filled out anonymously and on voluntary basis. To alleviate possible priming effects the students were only told that they participated in a research project on employer branding. We chose students for our study as they represent a main target group for recruiting activities (Berthon et al. 2005). All students are about to graduate soon, thus they are currently looking for job offers and know what they consider important when choosing an employer.

| HRM or Marketing | Business Information Systems | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | Germany | 85 | 48 | 133 |

| Denmark | 0 | 70 | 70 | |

| Total | 85 | 118 | 203 |

Table 1: Overview of study participants by degree program and country

Source: Authors

3.2 Dependent and independent variables

The dependent variable employer attractiveness was measured via a six-point likert scale (1 = very low to 6 = very high) on the basis of five items. The items were taken from the study of Turban and Keon (1993) and translated into German. An example of an item was „I would very much like to work for this organization“. Reliability estimates yielded a Cronbachs α of .85. The technology acceptance scale was taken from Neyer, Felber and Gebhardt (2012). It consists of four items, also based on a six-point likert scale. Cronbachs α of the scale is .91. To perform a two-factorial analysis of variance though the variable was transformed to an ordinal scale (ratings 1 and 2 = low, rating 3 and 4 = medium, ratings 5 and 6 = high).

To determine the effect of the AI-based speech recognition personality test on employer attractiveness, we used a full-factorial scenario-based online experiment. For this purpose, two different versions of a job advertisement for a graduate program were created. The job advertisement is based on a real existing one of a multinational company. One version of the job advertisement refers clearly to the use of an AI-based speech recognition personality test, the other does not contain this information.

Furthermore, to ensure realism, effectiveness of the manipulations and understandability of our questionnaire, we performed a pretest with 20 students.

3.3 Results

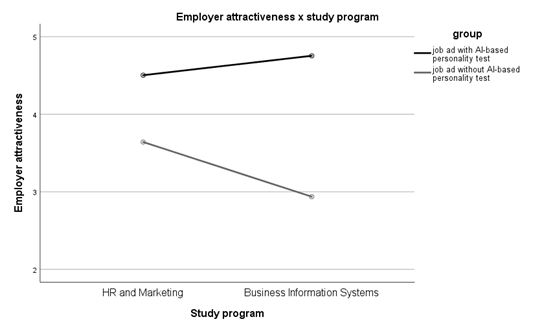

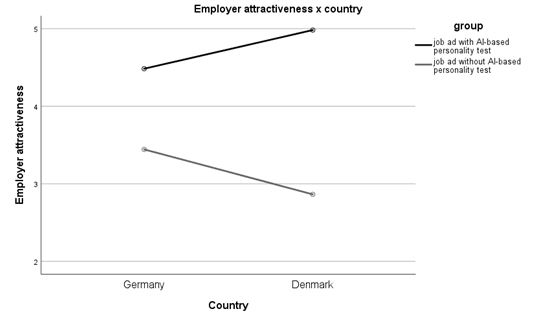

Two-factorial analyses of variance were performed to test for the hypotheses. Figures 1, 2 and 3 all show that companies posting job advertisements with reference to AI-based personality tests are considered more attractive than those that do not post such job advertisements, thus conforming hypothesis 1 (Ftech. acceptance (1, 193) = 30.30, p < .001, η2 = .136; Ffield of study (1, 195) = 78.45, p < .001, η2 = .287; Fcountry-specific (1, 195) = 107.77, p < .001, η2 = .356).

Hypothesis 2 cannot be confirmed (F (2, 193) = .352, p = .704, η2 = .004). The interaction between both independent variables is also not significant (F (2, 193) = .345, p = .709, η2 = .004).

Hypothesis 3 is confirmed by the interaction between both independent variables (F (1, 195) = 9.97, p < .01, η2 = .049). In addition, support for confirming hypothesis 4 is found. The interaction between both independent variables is significant (F (1, 195) = 12.54, p < .001, η2 = .060).

Figure 1: Results of the interaction effect: Employer attractiveness x technology acceptance

Source: Authors

Figure 2: Results of the interaction effect: Employer attractiveness x qualification (study program)

Source: Authors

Figure 3: Results of the interaction effect: Employer attractiveness x country

Source: Authors

4 Discussion

Overall, the contributions of our study are as follows: Firstly, we were able to provide first empirical evidence supporting that the use of modern AI-based methods in the context of personnel selection and employer branding has a positive effect on perceived employer attractiveness. Within this respect, our findings provide HR communication with the necessary knowledge on how to design respective employer branding campaigns. Consequently, recruiting communication material should display and describe new AI-based methods clearly to increase the employee’s perception of the potential employer. However, our results also show that there is no significant effect of potential employees’ technology acceptance on AI-related employer attractiveness. Thus, HR communication containing reference to AI will not bear the risk of provoking refusal among those potential employees who probably do not show a high technology affinity.

Secondly, according to our analyses, both qualification background as well as nationality significantly interacted with displaying AI-based methods in job advertisements on employer attractiveness. More specifically, our results indicate that AI in job advertisements leads to a positive response, especially from potential employees who have IT qualifications. This is in line with other empirical studies, as described in section 3.3. Based on these findings, HR communication addressing potential employees with IT qualifications should make use of AI-based methods in job advertisements to increase their employer attractiveness and differentiate from competing job advertisements. Inversely, if the reference to AI does not exist, this leads to a comparatively more negative rating of employer attractiveness.

Thirdly, country-specifics also appear to have a moderating influence on AI-related employer attractiveness. Compared to the German sample, Danish respondents reacted significantly more positively if the job advertisement contains a reference to AI. Inversely, the opposite effect was shown if the job advertisement did not contain the reference. This may be due to the fact that digitization is much more widespread in Danish society than in German society. This finding is supported by, e.g., the European Commission’s study on Digital Economy and Society Index, indicating that Denmark is among the most advanced digital economies in the European Union, outperforming Germany (European Commission, 2020). In summary, AI-related job advertisements always effect in a comparatively enhanced employer attractiveness. This effect is even stronger among those potential employees, where a high country-specific digital acceptance will be found.

As with most studies, our study is also subject to some limitations. Firstly, although our experimental research design helps to control for undesirable and confounding effects we measure intentional behavior. We tried to counter this fact by creating a realistic and understandable scenario in our study design. Nevertheless, future studies should replicate our findings in a real setting, probably also testing for observable application behavior based on secondary data.

Secondly, our sample is limited in size and was collected in Germany and Denmark only. Accordingly, we cannot generalize our findings and transfer them to other countries. Consequently, we encourage researchers to replicate our results in further international, multi-country settings.

Thirdly, determinants of employer attractiveness are manifold. Although we have developed the selection of possible moderating variables on the basis of an in-depth analysis of the current literature in the field, and therefore believe that our choice is well founded, we cannot rule out that other moderating variables would also have been more appropriate and led to more significant effects.

Literatúra/List of References

- Albert, E., 2019. AI in talent acquisition: a review of AI-applications used in recruitment and selection. In: Strategic HR Review. 2019, 18(5), pp. 215-221. ISSN 1475-4398.

- Alnıaçıka, E., Alnıaçıka, Ü., Eratb, S. and Akçin, K., 2014. Attracting talented employees to the company: Do we need different employer branding strategies in different cultures? In: Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences. 2014, 150, pp. 336-344. ISSN 1877-0428.

- Alshathry, S., O’Donohue, W., Wickham, M. and Fishwick, S., 2014. National culture as an influence on perceptions of employer attractiveness. In: AT Business Management Review. 2014, 10(1), pp. 101-111. ISSN 1813-0534

- Arbaugh, J. B., 2010. Online and blended business education for the 21st Century: Current and future directions. In: Chandos Learning and Teaching Series. 2010. ISSN 1813-0534. [online]. [cit. 2020-02-11]. Available at: <https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-1-84334-603-6.50009-6>

- Arntz, M., Gregory, T. and Zierahn, U., 2016. The risk of automation for jobs in OECD countries: A comparative analysis. In: Social, Employment and Migration Working Paper. 2016, pp. 189, Paris.

- Berthon, P., Ewing, M. and Hah, L. L., 2005. Captivating company: dimensions of attractiveness in employer branding. In: International Journal of Advertising. 2005, 24(2), pp. 151-172. ISSN 1759-3948.

- Brahmana, R. K. and Brahmana, R., 2013. What factors drive job seekers attitude in using e-recruitment. In: The South East Asian Journal of Management. 2013, 7(2), pp. 123-134. ISSN 1978-1989.

- Bührig, J., Guhr, N. and Breitner, M. H., 2011. Technologieakzeptanz mobile Aapplikationen für Campus-Managemement-Systeme. In: GI-Jahrestagung.

- Davis, F. D., Bagozzi, R. P. and Warshaw, P. R., 1992. Extrinsic and intrinsic motivation to use computers in the workplace. In: Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 1992, 22(14), pp. 1111-1132. ISSN 1559-1816.

- Davis, F. D., 1989. Perceives usefulness, perceives ease of use, and user acceptance of technology. In: MIS Quaterly. 1989, 13(3), pp. 319-340. ISSN 2162-9730.

- Davis, F. D., Bagozzi, R. and Warshaw, P., 1989. User acceptance of computer technology: A comparison of two theoretical models. In: Management Science. 1989, 35(8), pp. 982-1003. ISSN 1526-5501.

- Davis, F. D., 1986. A technology acceptance model for empirically testing new end-user information systems: Theory and results. Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Sloan School of Management.

- European Commission, 2020. Digital economy and society index (DESI) 2020. [online]. [cit. 2020-06-22]. Available at: <https://ec.europa.eu/digital-single-market/en/desi>

- Fishbein, M. and Ajzen, I., 1975. Belief, attitude, intention and behaviour: An introduction to theory and research. Boston: Addison-Wesley, 1975. ISBN 978-0201020892.

- Frey, C. B. and Osborne, M. A., 2017. The future of employment: How susceptible are jobs to computerization? In: Technological Forecasting and Social Change. 2017, 114(C), pp. 254-280. ISSN 0040-1625.

- Gbolahan, O. and Mutula, S., 2015. The influence of national culture on the performance expectancy of e-parliament adoption. In: Behaviour and Information Technology. 2015, 34 (5), pp. 492-505. ISSN 1362-3001.

- Ginner, M., 2018. Akzeptanz von digitalen Zahlungsdienstleistungen. Wiesbaden: Springer, 2018. ISBN 978-3-658-19705-6.

- Godhue, D. L. and Thompson, R. L., 1995. Task-technology fit and individual performance. In: MIS Quaterly. 1995, 19(2), pp. 26-42. ISSN 2162-9730.

- Gowan M. A., 2004. Development of the recruitment value proposition for geocentric staffing. In: Thunderbird International Business Review. 2004, 46(6), pp. 687-708. ISSN 1096-4762.

- Granic, A. and Marangunić, N., 2019. Technology acceptance model in educational context: A systematic literature review. In: British Journal of Educational Technology. 2019, 50(5), pp. 2572-2593. ISSN 0007-1013. [online]. [cit. 2020-02-11]. Available at: <https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12864>

- Harzing A. W., 2004. Ideal jobs and international student mobility in the enlarged European Union. In: European Management Journal. 2004, 22(6), pp. 693-703. ISSN 0263-2373.

- Hill, C. E., Loch, K. D., Straub, D. W. and El-Sheshai, K., 1998. A qualitative assessment of Arab culture and information technology transfer. In: Journal of Global Information Management. 1998, 6(3), pp. 29-38. ISSN 1062-7375.

- Hofstede, G., 1980. Culture’s consequences: International differences in work-related values. Beverly Hills: Sage Publications, 1980.

- Hofstede, G., 2001. Culture’s consequences: comparing values, behaviors, institutions, and organizations across nations. Beverly Hills: Sage Publications, 2001. ISBN 978-0803973244.

- Mumford, M. D., 2000. Managing creative people: Strategies and tactics for innovation. In: Human Resource Management Review. 2000, 10(3), pp. 313-351. ISSN 1053-4822.

- Neyer, F., Felber, J. and Gebhardt, C., 2016. Kurzskala zur Erfassung von Technikbereitschaft (technology commitment). Zusammenstellung sozialwissenschaftlicher Items und Skalen, 2016. [online]. [cit. 2020-02-11]. Available at: <https://doi:10.6102/zis244>

- Precire Technologies, 2020. [online]. [cit. 2020-02-26]. Available at: <https://precire.com/technologie/>

- Rogers, E. M., 2010. Diffusion of innovations. New York: The Free Press, 2010. ISBN 9780028740744.

- Salge, C., Glackin, C. and Polani, D., 2014. Empowerment – an introduction. In: Prokopenko M. (eds). Guided self-organization: Inception, emergence, complexity and computation, Vol. 9. Springer: Berlin and Heidelberg.

- Quiring, O., 2006. Methodische Aspekte der Akzeptanzforschung bei internationalen Medientechnologien. In: Münchner Beiträge zur Kommunikationswissenschaft. No. 6, Universität München. [online]. [cit. 2020-02-11]. Available at: <https://doi.org/10.5282/ubm/epub.1348>

- Schmidt-Atzert, L., Künecke, J. and Zimmermann, J., 2019. TBS-DTK Rezension: PRECIRE JobFit. In: Report Psychologie. 2019, 44(7/8), pp. 19-21. ISSN 0344-9602.

- Sommer, L., Heidenreich, S. and Handrich, M., 2017. War for talents – how perceived organizational innovativeness affects employer attractiveness. In: R&D Management. 2017, 47(2), pp. 299-310. ISSN 0033-6807.

- Sparrow, P., 2009. Handbook of international human resource management: Integrating people, process, and context. Wiley-Blackwell, 2009. ISBN 978-1-405-16740-6.

- Straub, D. W., Keil, M. and Brenner, W. H., 1997. Testing the technology acceptance model across cultures: a three country study. In: Information and management. 1997, 33(1), pp. 1-11. ISSN 0378-7206.

- Straub, D. W., 1994. The effect of culture on IT diffusion: E-mail and FAX in Japan and the U.S. Information. In: Systems Research. 1994, 5(1), pp. 23-47. ISSN 1099-1743.

- Tekin, H. and Tekdogan, O. F., 2015. Socio-cultural dimension of innovation. In: Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences. 2015, 195, pp. 1417-1424. ISSN 1877-0428.

- Turban, D. B. and Keon, T. L., 1993. Organizational attractiveness: An interactionist perspective. In: Journal of Applied Psychology. 1993, 78(2), pp. 184-193. ISSN 0021-9010.

- Upadhyay, A. and Khandelwal, K., 2018. Applying artificial intelligence: implications for recruitment. In: Strategic HR Review. 2018, 17(5), pp. 255-258. ISSN 1475-4398.

- Van Esch, P. and Black, J. W., 2019. Factors that influence new generation candidates to engage with and complete digital, AI-enabled recruiting. In: Business Horizons. 2019, 62(6), pp. 729-739. ISSN 0007-6813.

- Van Everdingen, Y. M. and Waarts, E., 2003. The effect of national culture on the adoption of innovations. In: Marketing Letters. 2003, 14(3), pp. 217-232. ISSN 0923-0645.

- Van Hoye, G. and Lievens, F., 2009. Tapping the grapevine: a closer look at word-of-mouth as a recruitment source. In: Journal of Applied Psychology. 2009, 94(2), pp. 341-352. ISSN 0021-9010.

- Veiga, J. F., Floyd, S. and Dechant, K., 2001. Towards modelling the effects of national culture on IT implementation and acceptance. In: Journal of Information Technology. 2001, 16(3), pp. 145-158. ISSN 1466-4437.

- Venkatesh, V. and Bala, H., 2008. Technology acceptance model 3 and a research agenda on interventions. In: Decision Sciences. 2008, 39(2), pp. 273-315. ISSN 0011-7315.

- Venkatesh, V., Morris, M., Davis, G. and Davis, F., 2003. User acceptance of information technology: Toward a unified view. In: MIS Quarterly. 2003, 27(3), pp. 425-478. ISSN 2162-9730. [online]. [cit. 2020-02-11]. Available at: <https://doi:10.2307/30036540>

- Weitzel, T., Maier, C., Oehlhorn, C., Weinert, C., Wirth, J. and Laumer, S., 2018. Mobile Recruiting – Ausgewählte Ergebnisse der Recruiting Trends 2018 und der Bewerbungspraxis 2018. Research Report, Otto-Friedrich-Universität Bamberg.

- Wilson, H. J., Daugherty, P. R. and Morini-Bianzino, N., 2017. The jobs that artificial intelligence will create. In: MIT Sloan Management Review. 2017, 58(4), pp. 13-16. ISSN 1532-9194.

Kľúčové slová/Key words

employer branding, employer attractiveness, artificial intelligence

značka zamestnávateľa, atraktivita zamestnávateľa, umelá inteligencia

JEL klasifikácia/JEL Classification

M31, M51

Résumé

Umelá inteligencia pri výbere personálu a jej vplyv na atraktivitu zamestnávateľa

Získanie a udržanie talentovaných zamestnancov sa stalo jednou z najnaliehavejších výziev pre spoločnosti v ich boji za dosiahnutie a udržanie konkurenčnej výhody. V tejto súvislosti zohráva dôležitú úlohu hodnotenie personálu a jeho výber. Na jednej strane môžu pomôcť jeho metódy pri rozlišovaní medzi vhodnými uchádzačmi a menej vhodnými. Na druhej strane hodnotenie personálu a výber ovplyvňuje vnímanú atraktivitu zamestnávateľa. Preto úzko súvisí so značkou zamestnávateľa.

V priebehu digitalizácie sa umelá inteligencia čoraz viac využíva na priťahovanie a výber personálu. Zavádzajú sa nové nástroje. Napríklad počítačom podporované rozpoznávanie reči sa údajne môže použiť na generovanie osobnostných profilov žiadateľov. Zdá sa však, že vedecká diskusia na túto tému v oblasti relevantných marketingových nástrojov výrazne zaostáva. Z vedeckého hľadiska je otázne nielen to, či sú tieto nástroje prognosticky platné, ale aj to, či ich žiadatelia akceptujú.

V rámci experimentálnej štúdie sa teda skúmajú dve dôležité otázky: Aký vplyv majú inzeráty na zamestnanie na vnímanú atraktivitu zamestnávateľa, ak je na výber personálu výslovne uvedené použitie rozpoznávania reči pomocou počítača? Do akej miery je vzťah medzi propagáciou práce s odkazom a bez odkazu na rozpoznávanie reči ovplyvnený atraktivitou zamestnávateľov v podmienkach akceptácie technológií, rozdielmi v jednotlivých krajinách a kvalifikáciou? Odpovede na tieto otázky zlepšia naše chápanie reakcií uchádzačov na výberové konania. Okrem toho poskytujú dôležité informácie pre prax riadenia ľudských zdrojov v kontexte značky zamestnávateľa.

Recenzované/Reviewed

4. March 2020 / 8. March 2020