The methodology used in this research is a field survey conducted during the 21st International Traditional Crafts Fair in Algeria. The sample consists of 228 artisans, representing 30% of the fair’s participants, with a distribution of 46% women and 54% men. Data were collected using a structured questionnaire based on the three key innovation factors defined by the „3Ts“ model. The data were then analyzed using descriptive analysis and cross-tabulation techniques.

The results indicate that while artisans remain attached to traditional methods, they recognize the importance of innovation in preserving and promoting their craftsmanship. However, the adoption of information and communication technologies is limited, highlighting a need for increased training. The study also demonstrates the potential of clusters to enhance collaboration among artisans, facilitate knowledge exchange and improve their competitiveness in the global market. Finally, the article underscores the importance of protecting artisanal creativity through collective marks and geographical indications.

1 Introduction

Artisan entrepreneurs and artisan enterprises are subjects of research in various disciplines, particularly those related to economic and social sciences. Moreover, the roles played by craftsmanship in strengthening social ties on one hand and its role in innovation processes on the other, are beginning to be better understood. It should be noted that craftsmanship involves the production of products or services through specific know-how that relies primarily on the direct manual contribution of the artisan. The special nature of artisanal products is based on their distinctive characteristics, which can be utilitarian, aesthetic, artistic, creative, cultural, decorative, functional, traditional and even symbolic.

In Algeria, Ordinance 96/01 of January 10, 1996, divides crafts and trades into three distinct domains: production crafts, service crafts and artistic crafts. These domains can be practiced individually, in cooperatives, or in artisanal enterprises under four forms: sedentary, itinerant, fairground, or at home. Artistic craftsmanship is characterized by its originality, uniqueness and creativity.

Augais and Hazet (2022) indicate that: „Artisans are passionate men and women mastering complex skills, capable of transforming materials to create unique pieces or small series. They shape, restore and imagine exceptional works at the crossroads of beauty and utility.“

In this context, Boutillier Sophie (2017) defines entrepreneurial activity as: „the discovery of profit opportunities that other individuals had not discovered before. In these conditions, the entrepreneur’s profit is the reward obtained partly by chance and thanks to his ability to anticipate how individuals will react to change.“

Furthermore, according to Mathieu Bedard (2016): „Entrepreneurs are essential to economic activity. It is through their decisions that goods and services are produced and therefore supply meets demand. But the entrepreneur is also the figure that allows the economy to go beyond the simple mechanics of supply and demand. It is he who identifies new ways to solve the economic problem (what to produce, for whom to produce, how to produce).“

These definitions confirm that entrepreneurship is the engine of continuous progress, society and the economy of countries. However, it is also a complex concept that interacts with multiple dimensions, including psychological, sociological and behavioral aspects. It should also be noted that entrepreneurship is a complex asset that requires certain qualities, values and essential skills to help entrepreneurs realize and develop a project. Thus, the entrepreneur becomes the vector of change and project growth, as his action can contribute to accelerating the elaboration, dissemination and implementation of innovative ideas.

However, in the field of craftsmanship, we notice that today’s artisan remains more resistant to innovation because he is aware that it is the local ancestral know-how that allows him to preserve the authenticity of his products and guarantees differentiation from his competitors. Yet artisans, in particular, need to develop their innovation capacity in order to increase the attractiveness of their territory (region) and their development capacity.

For our part, in this present research work, we will focus on the case of the Algerian artisan to identify his abilities to develop his innovation capacity on one hand and to make known the contribution of the cluster approach in supporting artisans in their entrepreneurial and innovation processes on the other. We will focus more precisely on the concept of clusters in artistic craftsmanship by appropriating the principles of creative economy theory and the concept of the three Ts. This will allow us to highlight the necessary conditions for the formation of clusters and to understand the requirements for their proper functioning and sustainability.

In this regard, the application of Richard Florida’s rule of three Ts (Technology, Talent and Tolerance) seems relevant for analyzing the essential factors for the development of artisanal activities, as well as preserving regional specificities and transforming them into differentiation levers, in order to increase local competitiveness in a global market framework.

By linking the cluster concept and the rule of the three Ts, we will attempt to answer the following main question:

To what extent does the cluster approach enable artisan entrepreneurs to appropriate innovation capabilities and undertake joint projects?

From this main issue, three sub-questions arise:

• S/Q1: Are artisans able to use ICT and other technological tools (computer, CAD, the web, etc.) to promote their activity?

• S/Q2: Do artisans possess the talent necessary to innovate in their field of activity?

• S/Q3: Are artisans able to lead a collective project?

In order to better understand the elements of response to the questions posed, it is essential to formulate the following research hypotheses:

Firstly, formulating a main hypothesis is deemed necessary:

MH: Talented artisans possess the knowledge and skills that allow them to differentiate themselves from others, but to meet the new market requirements, they have developed their ability to integrate new production techniques (technology) and other promotional tools to better market their product and defend their positioning on the market.

In this regard, three sub-hypotheses seem imperative to formulate:

• S/H1: Artisans are relatively able to use technology but with low mastery, hence the necessities of the cluster approach.

• S/H2: With the help of the cluster approach, artisans could develop their capacity to improve their knowledge and skills.

• S/H3: The methodology of the cluster approach will develop group work skills among artisans and their capacity for collective intelligence.

Our research investigations will first focus on the conceptual framework of the rule of the three Ts, then on the notion of the cluster approach, its origin, its development mode and its operational mode. Subsequently, we will present our field study, which will focus on the application of the rule of the three Ts to identify the degree of artisans’ aptitude for innovation and to justify the importance of artisans’ appropriation of the cluster approach.

The results will be presented and discussed in the last section of this research work.

2 Literature review

2.1 The cluster approach: Origin and development

In recent years, cluster approaches have attracted significant interest from the scientific community. Many studies have focused on clusters in various fields. The enthusiasm for this concept is justified by the context of intense competition between countries and regions, where territories must continually improve their competitive positioning to adapt to the globalization of interactions with its associated opportunities and risks. The concept of clusters, introduced by Porter in 1990, has gained great popularity among governments concerned with increasing the attractiveness of their territories, seeing this concept as an important tool for creating industrial clusters. According to William R. Kerr and Frederic Robert Nicoud (2019), Silicon Valley and its success in creating a knowledge-based economy greatly motivated governments around the world to create „high-tech clusters in their territories.“

Porter (1990) defines a cluster as a geographical concentration of interconnected companies, specialized suppliers, service providers, firms in related industries and associated institutions (universities, standardization agencies, or professional organizations, for example) in a particular field, which compete and cooperate. He extends his definition to any geographical space (country or group of countries), no longer delimiting the cluster by its organizational and competitive boundaries.

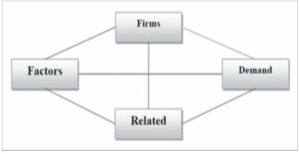

Figure 1: The Porter diamond approach to clusters

Source: Porter (1990, p. 13)

Reading the above diagram highlights the different components of a cluster, namely:

• Firms: These are the companies involved in producing products and services identifying the cluster.

• Related: These are companies that provide other products and services, but to a similar customer base (Demand) and can thus interact with both the customer and the „Firms“ of the cluster.

• Factors: These are structural environmental elements (institutions, infrastructure, universities, support, etc.).

• Demand: This represents specific demands that activities enable both specialization and external growth.

However, according to Amina Kaci and Lila Amiar (2022), there is a consensus around the following three elements:

• An economic understanding of the cluster, which emphasizes „the sectoral dimension and makes the cluster a grouping of companies linked by customer-supplier relationships or by common technologies, employment areas, customers, or distribution networks.“

• A relational understanding based on networking of actors and „often highly variable geographical proximity.“

• A more territorial understanding sees the cluster as a place, a pole, with a critical mass of actors „(…) and this thanks to a strong concentration of companies, research and training organizations, operating in a particular field, relying on the presence of venture capital, the state and local authorities and aiming for international excellence. The territorial anchoring of the various actors is therefore very strong.“

In Algeria, this approach is relatively recent. It emerged in 2007 during the National conference on industrial strategy, organized by the Ministry of Industry. During this conference, the concept of Integrated industrial development zones (ZIDI) was introduced, with incentives for the establishment of industrial clusters. It is important to mention that in the early 2010s, there were no significant groupings of industrial enterprises, so it was not possible to talk about industrial clusters. In the 1970s, „only the concepts of industrial zones (public industrial complexes) and later activity zones (SMEs) were developed and implemented“.

It was only in 2008 that the first initiatives to support localized productive systems (LPS) were introduced by the Algerian Government in the artisanal sector. Later, the German cooperation set up the DEVED (sustainable economic development) program of the GIZ Cooperation Agency, to support the creation of clusters in Algeria in the construction, ship repair and agriculture sectors.

Other clusters have also been identified, such as the milk cluster in Ghardaïa and the olive oil cluster in Bouira. For our part, we will focus on the copper artisans cluster in Constantine and the jewelry artisans cluster in Batna. The Constantine cluster is the largest copperware cluster in Algeria and represents 70% of national production. The relevance of the cluster approach in the field of craftsmanship aims to develop artisans’ capabilities to work collaboratively and innovate while preserving the specificities of their region and their creative uniqueness. Indeed, innovating as a team in a creative economy sector requires a significant effort to engage all knowledge holders in creating an innovative solution that constitutes a defensible and sustainable competitive advantage. Thus, coordinating and animating artisan entrepreneurs require highlighting the general interest of economic and socio-cultural synergies that could be generated from their involvement in collective work.

In the field of craft marketing, collective work plays a crucial role by fostering collaboration and competitiveness within communities of specialized artisans (Munoz and Laoudj 2013). These geographical or virtual groupings allow artisans to share resources, knowledge and business opportunities. By collaborating, they enhance their collective visibility, leverage economies of scale for production and marketing and create more efficient distribution networks (Laoudj 2017). Clusters also encourage innovation and creativity by facilitating the exchange of ideas and the development of new marketing approaches tailored to the particularities and authenticity of handmade products (Colbert 2007). Thus, these groupings are beneficial not only commercially but also culturally, contributing to the preservation, protection and promotion of traditional crafts (WIPO 2003).

2.2 Craftsmanship: an archetypal sector of the creative economy

In light of our literature review, we emphasize that the relationship between craftsmanship and innovation is very close. Craft products are characterized by „their distinctive values, which can be utilitarian, aesthetic, artistic, creative, cultural, decorative, functional, traditional, symbolic and socially or religiously significant“ (WIPO Guide 2016, p. 2).

This definition presents craftsmanship as an archetypal sector of the creative economy, highlighting craftsmanship and human intelligence. This economy, according to the United Nations, is a viable growth driver for all countries, especially for developing countries.

Craft is characterized by a high proportion of manual work. However, the craftsman is more of a service provider than a producer, because he usually only manufactures individual custom-made products on customer orders and does not produce a range of goods. This service provider function also characterizes the employees: Often everyone is in control of every production step (Diedrich 2022).

Furthermore, creativity is perceived as a decisive source of competitive advantage for the future at the heart of the progressive emergence of a knowledge society, based on the knowledge economy.

Additionally, it is noteworthy that according to Pierre Poinsignon (2022), creative industries include plastic arts, advertising, architecture, art, craftsmanship, design, fashion, publishing, film and video, television and radio, interactive leisure software, music, performing arts, photography, software and computer services. All these activities have a strong component of creative skills and can generate income. These creative industries represent a broad domain that can combine several creative activities with groups of activities with higher technology and service intensity.

2.3 Innovation in artisanal enterprises

Since 2008, Polge has demonstrated the importance of innovation in artisanal enterprises, without necessarily the awareness of their owner-managers. His work has helped clarify how tradition can be a lever for innovation in an artisanal context. These innovations exist both at the technical and market levels. However, very few studies have focused on the origins of innovation and creation in the crafts sector. According to the United Nations report entitled „Perspectives on the Creative Economy“ published in 2022, „creative sectors refer to cycles of creation, production and distribution of goods and services in which creativity and intellectual capital are the main inputs“.

Additionally, another UNESCO report published in 2017 states that the creative economy is „an economy where imagination is the raw material and skills are the main infrastructure“.

Therefore, artisans nowadays must innovate to adapt their artisanal production to the demands of the global economy, where skills and productivity are fundamental to competitiveness in the market.

2.4 The actors of the creative economy and the rule of the 3Ts:

John Howkins, the father of the notion of the „creative economy“, explains this phenomenon as „a process of collaboration and sharing: consumers can be initiators (open-source software, video games, travel industry) and talk to producers. It is a circular process between initiators, users/consumers, production and distribution. What took several years can now take a few days“ (Poinsignon 2022).

The concept of the creative economy and the creative class emerged in academic circles in the United Kingdom and the United States in the 1990s. In London, the creative economy was the second-largest economic sector in 2009, with 525,000 employees and an annual turnover of £30 billion.

The Two Banks Institute considers this economy as an approach to the development of creative industries. These industries cover a wide variety of professions, including high-tech, entertainment, journalism, finance, or fine crafts. It is a cycle of production and distribution of goods and services in which the basic factor is the use of intellectual capital (Talent). In his work, Florida (2002) mentioned that economic development depends on the presence of a category of active population called the „creative class,“ which includes artists, writers, painters, etc. Indeed, the creative class is considered a factor in local economic development.

Florida asserts that the most creative classes adhere to the rule of the three T’s, or combine the maximum of these 3Ts (Technology, Talent and Tolerance).

The author’s objective is to identify the factors that contribute to attracting creative capital. In this regard, Florida concludes that the creative class is attracted to cities that prioritize tolerance and diversity. According to Florida, creative capital depends on the degree of creativity and not only on the level of education of the population. This human capital positively influences the development of cities. To attract this creative capital, urban spaces must be open to creativity, tolerant and characterized by diversity on ethnic and cultural levels.

Anderson (1985), on the other hand, identifies six factors that may correspond to environments favorable to innovation, including financial stability, efficient transportation infrastructure to facilitate communications and some instability regarding technological and scientific futures, which is a development condition for a creative environment. Florida thus relies on an existing train of thought, one carried by Jane Jacobs, American sociologist Robert Lang, Berkeley and Claude Fischer, but he updates the idea that the city is the place of creativity and innovation due to its cultural and social diversity.

2.5 Social capital and collective approach at the heart of the 3T’s

Donsimoni and Perret (2008) emphasize that mobilizing and working together populations and local authorities have become a major challenge. In Algeria, the cluster approach quickly had a positive effect on bringing together more than 150 artisans between 2014 and 2017. Indeed, artisans agreed to work within a cluster and succeeded in securing significant markets. It should be noted that according to Bruno Lefèvre (2019), „cultural clusters are tools for promoting symbolic vitality.“

Moreover, the arts and cultural industries have become full-fledged allies of economic and territorial development policies. Arts and artists are placed at the forefront of the value chain of new and vast „creative industries“, if not at the radiant center of diffuse creativity benefiting the entire economy and society.

Finally, based on the above statements, we deduce that social capital, as defined by Woolck and Narayan, is like all the norms and networks that facilitate collective action. For Loudiyi et al., (2004), the creation and strengthening of social capital to generate territorial development require identifying all forms of social capital that allow social groups in a territory to control future developments.

Other authors have addressed the issue of territorial development from a socio-economic point of view, specifically viewing the „creative economy“ as an alternative for the development of cities and regions using localized social networks. An economy that connects the cultural world with the economic world constitutes, for our study, an appropriate analytical model.

Courcoux (2008) emphasizes in his writings that after the management of material resources in the 1960s, energy resources in the 1970s, information in the 1980s and human resources in the 1990s, the new wealth of nations is indeed that of innovation. In this regard, the creative economy, according to Patrick Boillat (2007), is by definition innovative; it is not only subject to the laws of competition but also a weapon of competitiveness, especially for territories.

„When we talk about differentiation strategy in cultural matters, we often come back to a geographical logic, to a logic of territory.“ Alan J. Scott complements the previous statement based on the originality and origin of the product to create a competitive advantage through difference: „Just as each firm differentiates its products in a specific way, products are frequently differentiated based on the places they come from. This establishes certain poles of cultural economy, positions of quasi-monopoly.“ We proceed in our exploratory study with the application of Florida’s „3T“ rule; it is often used to assess the creative intensity of territories (environments) and its effect on the economy.

3 Data and method

3.1 Presentation of the study

Our study aims to examine the population of artisan entrepreneurs belonging to the brassware cluster in the province of Constantine, as well as to that of the jewelry cluster in the province of Batna. The choice of these two clusters is justified by:

• The creative intensity found among artisans in these two regions and its positive effect on the country’s economy on the one hand.

• The Algerian authorities’ desire to encourage and safeguard trades with export potential on the other hand.

Furthermore, this research work constitutes a research project initiated by the PERMANAN research laboratory (HEC Algiers) and UNIDO (United Nations Industrial Development Organization). The objective of this project is to introduce the concept of clusters into cultural and creative industries, in a support process for countries in the Southern Mediterranean. For Algeria, the choice was made on the two clusters mentioned above, as pilot clusters.

The work we present here is exploratory; our objective is to understand to what extent belonging to a cluster can help artisan entrepreneurs appropriate innovation capabilities. To do this, we interviewed artisans about the elements that can inform us about their level (aptitude) of innovation appropriation, while respecting Richard Florida’s concept of the „3T“s.

• The objective of the research is to identify favorable conditions for undertaking innovation, based on a model (the 3T rule) and a methodology based on collaborative work (cluster).

• The sample is defined by convenience sampling method, comprising more than 30% of the total number of participants at the trade fair.

• The sample is representative because the selection of exhibitors is made by the organizer ANART according to several criteria such as seniority, membership in the cluster or another group, association, nucleus.

• Indeed, we conducted our survey during the 21st International Traditional Crafts Fair in Algeria, with a convenience sample of 228 exhibiting artisans, representing 30% of the sampling base (total number of participants), composed of 46% women and 54% men. To ensure a more homogeneous and representative sample, we selected artisans chosen by the organizing structure of the fair (ANART) according to acceptance criteria such as field of activity, experience, artisan card, affiliation with clusters, associations, nuclei, or cooperatives.

A. Studied population

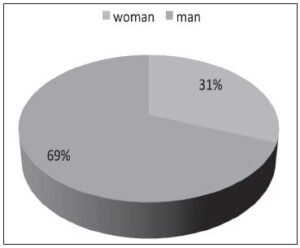

The field of artistic craftsmanship is the main component of our study population and men are always more active than women in all areas of craftsmanship. Moreover, it is observed that in the studied population (artistic craftsmanship), the rate of women is significant (31%) compared to the other two domains: goods production and services.

Figure 2: The fields of craftsmanship and the gender employment rate

Source: Chamber of Crafts and Trades, Statistical Bulletin (2017)

B. The brassware cluster in Constantine

Algerian brassware dates back to the Middle Ages and its style has evolved but still retains Ottoman influence. Its main consumers are households and although brassware artisans can be found in various provinces of Algeria (such as Algiers, Biskra, Ghardaïa and Tlemcen), Constantine currently accounts for 70% of the national brassware production.

The cluster comprises approximately 130 registered artisans at the Chamber of Crafts and Trades and around a hundred unregistered ones, generating an annual turnover of $2 million (including members such as raw material importers, wholesalers and traders and manufacturers and importers of machinery and equipment).

C. The jewelry cluster in Batna

This cluster has over 1000 artisans and generates approximately $60 million in turnover. Artisans in this region of Algeria, nestled in the heart of the Aures, are known for their exceptional and ancestral craftsmanship, emanating from a long tradition.

3.2 Methodology of the survey

The objective of our field study is to analyze the attitudes of artisans, which inform us about their abilities to organize within clusters and appropriate innovation capacities.

To achieve this, we collected data using a questionnaire developed and administered by our research team to artisans (the questionnaire axes are attached in the appendix).

The structure of this questionnaire is based on our reflection, which relies on the model of the „3T“ rule (technology, talent, tolerance); considered as sources of attractiveness of a territory (corresponding to the creative class) (Florida 2002) and as a source of innovation in a milieu (cluster) (Crevoisier 2001).

A. Study variables

The variables of our study are predefined in relation to the „3T“: Technology, Talent and Tolerance. We summarize them in the following table.

| « 3Ts » | Factors | Variables |

|---|---|---|

| Talent | Education level | Primary, secondary, university |

| Training (apprenticeship) | Entrepreneurship, business model, marketing | |

| New practices | Knowledge from others | |

| Experience | New craftsmanship, designer's knowledge, exhibitions, fairs years of seniority | |

| Tolerance | Diversity | Crafts: artisan craftsmanship |

| Collective spirit | Collective brand group purchase | |

| Openness to new ideas | Knowledge from others | |

| Technology | Work tools | Scanner, machines, computer photocopier |

| Internet | Websites, computer-aided design (CAD) |

Table 1: Definition of empirical study variables

Source: authors, innovation factors inspired by Florida (2002)

B. The questionnaire

Drawing inspiration from the conceptual framework mentioned in the literature review based on the works of Richard Florida (2002), John Howkins and Anderson (1985), the questionnaire was developed based on the three key innovation factors as presented by Richard Florida. It is structured into four parts focusing on questions related to the content of the „3T“ rule. The first part is reserved for economic and sociodemographic data of the artisans (identification form). The next three parts will address aspects related to innovation drivers as defined in the previous table (study variables).

The formulated questions are mostly closed-ended, according to the necessity of quantitative study: dichotomous single-choice and multiple-choice questions. All respondents are interviewed face-to-face with the assistance of doctoral researchers affiliated with the PERMANAN research laboratory at the Higher School of Commerce of Algiers (HEC Algiers).

C. Data analysis

We conducted our survey during the 21st International Traditional Crafts Fair in Algeria, from March 23 to 29, 2017, with a convenience sample of 228 exhibiting artisans, comprising 46% women and 54% men.

These artisans come from 48 wilayas (provinces) of the country, among which the wilayas of Algiers, Tizi-Ouzou, Boumerdes, Tlemcen, Bouira, Batna and Constantine were the most represented with various craft domains, according to regional specificity.

For our data analysis, we used descriptive analysis and cross tabulation (uni-variable and bi-variable analysis) using the SPSS software. This tool allowed us to accept or reject hypotheses and subsequently verify them.

4 Results

4.1 General typology of the sample

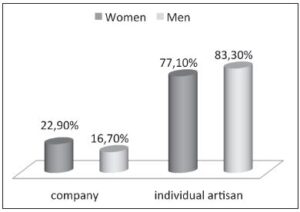

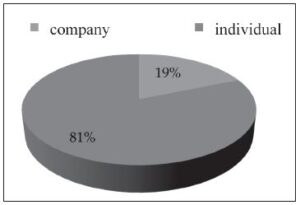

The activity is mainly managed by individual workshops, run by a man assisted by his wife and/or other family members. A workshop operates with an average of 1 to 10 employees, corresponding to the size of a small enterprise in the European Union.

Women are a minority in craft activities, but they tend to lead businesses rather than individual workshops, with more workers than men. They also have a higher level of education.

Figure 3: Mode of artisanal activity exercise (traditional craft art)

Source: authors

Regarding demographic aspects, we observe that the largest age group falls between 40 to 59 years old, with a secondary level of education. The results show that few young individuals enter the artisanal activity and those who do have an average or secondary level of education.

For over half of the artisans active in traditional craft art, 56% acquired their skills and learned their trade primarily through apprenticeship with master artisans, accounting for 29% of the total. 27% underwent professional training at an accredited vocational training center (CFPA) and nearly 18% are self-taught.

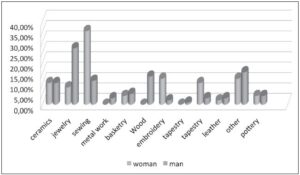

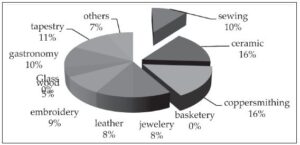

The studied sample contains a relative proportion of various crafts, with jewelry making and traditional clothing being the most represented, along with ceramics, while metalworking is very minimally represented.

Figure 4: Crafts of traditional craft art

Source: authors

4.2 The „technology“ lever (source of innovation)

4.2.1 Innovation: A factor in preserving craftsmanship

Preserving ancestral crafts poses a significant challenge for the sector. On one hand, artisans must innovate to meet new consumption trends to survive in a competitive market and on the other hand, they are responsible for conserving the identity and heritage of their country.

Furthermore, the obtained result clearly shows that respondents are convinced that innovation is a factor in preserving craftsmanship, with an 84% response rate.

4.2.2 Technology as a factor of innovation in crafts

The use of technology is considered by artisans as an important factor in the innovation of their products, with a response rate of 76%. Artisans express a positive perception of adopting new technologies, reflecting their ability and willingness to be integrated into an innovation-driven economy.

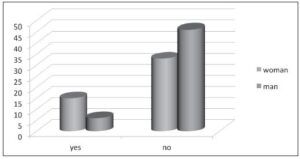

4.2.3 Internet use in the design of craft products

We found that the majority of respondents (artisans) do not use the internet in their activities. In fact, the results show that the number of women who use it is twice as high as that of men (see Figure 5). This demonstrates a greater ability on their part to adopt new communication and information techniques with the environment.

Figure 5: Internet use in the design of craft products

Source: authors

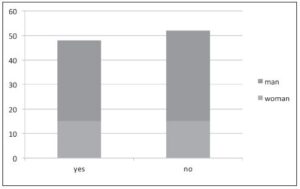

4.2.4 The use of computers in artisanal product production

According to the respondents, it appears that artisans generally have a positive perception regarding the necessity of introducing new technologies in the manufacturing of their products. However, the non-user respondents of computers for computer-aided design (CAD) in the product design phase represent twice as many as those who use it. This may be explained by the fact that artisans still remain attached to traditional inherited methods (see Figure 6).

Figure 6: Use of computers in artisanal production

Source: authors

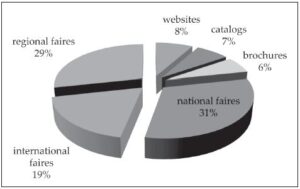

4.2.5 The use of websites for artisanal promotion

Only 8% of the responding artisans use a website to promote and sell their products.

Figure 7: Utilization of promotional techniques

Source: authors

The most commonly used technique by the respondents is participating in trade fairs. This allows them to have direct contact with their customers who can test, feel, touch and taste the product. Moreover, it enables them to sell a considerable quantity in a short amount of time compared to online sales (according to interviews with artisans).

4.3 Talent lever

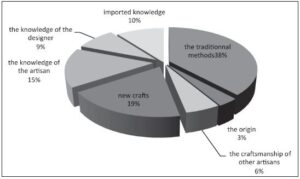

4.3.1 Knowledge used in artisanal product design

Regarding the design of artisanal products, artisans primarily rely on traditional methods, with a response rate of 38%. There is also a trend towards new craftsmanship, estimated at a rate of 19%. Artisans prefer to use their own knowledge rather than importing knowledge from other artisans or designers.

Figure 8: Knowledge used in artisanal product design

Source: authors

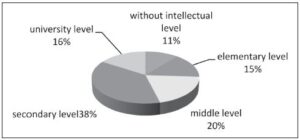

4.3.2 Level of education

38% of the responding artisans have a secondary level of education. This can be explained by the fact that craftsmanship primarily relies on inherited knowledge and skills, passed down from generation to generation through apprenticeship.

Furthermore, 16% of the respondents have a university education and 11% have a primary education. This demonstrates the emergence of a new trend where individuals with higher levels of education are engaging in artisanal professions. This could be seen as a positive indicator of talent development within this population.

Figure 9: Level of education among artisans

Source: authors

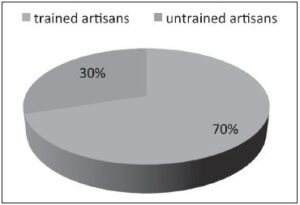

4.3.3 Proportion of trained and untrained artisans

The artisan card is one of the mandatory criteria for participating in the trade fair, requiring artisans to hold a certificate or diploma of training. This implies that all participating artisans must be trained in their crafts. However, according to the results obtained, 29% of artisans are not trained: either they do not possess the artisan card, or they have not necessarily undergone qualifying training. On the other hand, it is noteworthy that a high proportion, 64%, of artisans are trained in their craft.

Figure 10: Proportion of trained and untrained artisans

Source: authors

4.4 The „tolerance“ lever

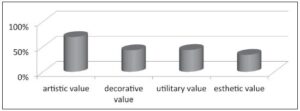

4.4.1 Diversity of values attributed to artisanal products

The results confirm that artisanal products are characterized by a strong diversity in their nature, form and value (artistic, utilitarian, etc.), which makes them unique. Furthermore, this diversity also arises from the various crafts practiced according to specific skills and inherent to each region. This is justified by the presence of more than 12 crafts at the fair. Thus, the various skills of artisans constitute a source of differentiation and the capacity for local development and competitiveness.

Figure 11: Values attributed to artisanal products

Source: authors

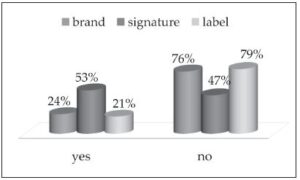

4.4.2 Protecting creativity

The legal registration of certification marks, collective marks, geographical indications, patents, designs, or creative models not only allows for identifying the source of an artisanal product but also ensures consistent quality of creativity, protecting artisans against illegal copies or imitations.

From our results, concerning the perception of artisans regarding the protection of their products, 53% of respondents put their signature on the product to identify it, while only 24% have a trademark or label (see Figure 12). This can be explained by a lack of awareness of product protection and ignorance of the important role of intellectual property in promotion and competitiveness.

Figure 12: Protection of artisanal products

Source: authors

4.4.3 Mode of activity

According to data from the National Crafts File (FNA), over 90% of active artisans operate individually. Cooperatives and artisanal enterprises represent less than 1% of the total. Artisans tend to work individually, with only 19% of respondents practicing their trade in enterprises, while 81% operate in their own workshops. This result confirms the characteristic of individual work in traditional and artistic craftsmanship, despite entrepreneurship training programs provided by chambers to support artisans.

Figure 13: Mode of practice in traditional craftsmanship

Source: authors

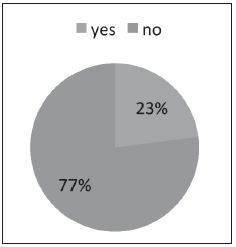

4.4.4 Financing of promotional activities, particularly participation in fairs and trade shows

The most commonly used promotional techniques by artisans are fairs and trade shows. Despite the high cost, 77% of respondents finance their participation themselves. Artisans now express their own willingness to communicate and promote their products.

Figure 14: Financing participation in the trade fair

Source: authors

4.4.5 Exporting artisanal products

Regarding the sale of traditional artisanal products in foreign markets, artisans face various bottlenecks related to logistics, financing and administrative burdens. Ceramicists and metalworkers represent the highest proportion in terms of exports. In other crafts, very few artisans export (less than 10%) and none in basketry. The carpet sector has seen a significant decline since the 1980s, with only 11% of respondents reporting exports.

Figure 15: Distribution of artisans by exported products

Source: authors

5 Discussion

The results pertaining to the first secondary question revealed that despite artisans’ strong attachment to ancestral methods in manufacturing, they are convinced that innovation is a solution for preserving craftsmanship. Furthermore, technology is considered a driver for innovation. However, many of them do not use the internet, CAD, or computers, neither in the commercial management of their activities nor in the design of their artisanal products. This suggests a need for cluster managers to implement a comprehensive training program for artisans, focusing on the information and communication technologies (ICTs) and computer literacy, as well as design, to address their technological inadequacy.

From these results, we confirm the first hypothesis that the cluster approach constitutes an effective support mechanism allowing artisans to master the use and integration of technology in their production, promotion and marketing activities with the aim of creating a competitive advantage through differentiation based on elements of art and cultural marketing (Colbert 2007) and Bourgeon-Renault (2009).

Indeed, the level of training in the craft and the educational level are not necessarily the main indicators of talent for artisans. However, it is essential to teach them marketing and project management practices for better entrepreneurship and project success, as revealed by the results related to the second sub-question.

Therefore, we confirm the second hypothesis stating that improving knowledge and skills in marketing techniques and project management through the cluster approach enables artisans to acquire the talent necessary for innovation. Regarding tolerance, the results related to the third sub-question showed that the cluster methodology could facilitate all types of interactions among stakeholders and cluster partners. As previously emphasized, the common interest of artisans could drive initiatives for sharing ideas and transmitting cultural knowledge and skills, thus fostering innovation.

Therefore, it is essential to protect artisans’ innovations, whether they are models, designs, or motifs originating from the region. These elements constitute values of distinction and differentiation through which artisans gain competitive advantages, enabling them not only to create wealth but also to create a competitive advantage through cultural differences.

Indeed, the final hypothesis is also confirmed, as the cluster approach will develop artisans’ ability to appropriate elements of collective intelligence, such as knowledge sharing, shared workspace, joint procurement and marketing. Additionally, financing new projects and ideas remains an important means of growth, thus being one of the main motivations for artisans to acquire innovation capability. Therefore, collective action is presented as an indispensable condition for financing innovation.

In conclusion, the cluster approach, by its definition, can build a creative capital (artisans) that, through collective intelligence, could engage in innovative entrepreneurial ventures. Furthermore, artisans are not currently organized into enterprises; individualistic culture dominates their trade. Therefore, the cluster methodology seems relevant to develop artisans’ abilities to work toward a common goal. Undertaking projects indicated by the cluster methodology and following a team-based implementation process encourage artisans to exchange knowledge and skills and generate new ideas. This helps build social ties facilitating the creation of social capital, which, through trust relationships, leads to what Florida calls „creative capital.“ The trust established encourages artisans to use others’ knowledge, such as that of designers.

6 Conclusion

The handicraft sector, given its institutional, organizational and structural instability, has seen very few of the objectives of its development policy come to fruition, despite all the institutional mechanisms expressed by the public authorities. Even though these mechanisms were mobilized with all existing human capacities, including artisans in the various crafts, which currently number around 340 activities and with the assistance of the 48 chambers overseeing the organization and implementation of action plans, the expected results within the framework of major strategic orientations in cooperation with foreign institutions, notably with the European Union through the upgrading and twinning programs (P3A), could have been achieved.

The observation we can make after our study is that the competitiveness of this sector depends heavily on the ability to integrate all its components in a participative entrepreneurial approach through new socio-organizational structures such as „clusters“. These clusters facilitate the transmission of ancestral and new knowledge and skills. Artisans cannot alone drive the levers of their growth upward if the infrastructures, supervisory institutions (CNAM, ANART and CAM) and local authorities do not meet the requirements of innovation.

Hence, the necessity for artisans to establish both trusting relationships and cooperation/competition relationships to create both differentiation and uniqueness in their products. Significant progress has been made, more or less in training, but there is still a huge amount of work to be done in other major pillars related to the „3T“, namely, territorial development, including innovation, ICT, financing and institutional mechanisms, organization and governance of artisanal supervisory institutions, as well as the promotion, protection of their creativity and the enhancement of local cultural heritage.

Literatúra/List of References

- Amdnigh, F. and Lahoucine, A., 2021. The creative class and public action in the process of creating creative territories, case of the old Medina of Marrakech. In: Space Geography and Moroccan Society Journal. 2021, 45/46. ISSN 1113-8270.

- Andersson, A. E., 1985. Creativity and regional development. In: Papers in Regional Science. 1985, 56(1), 5-20. ISSN 1435-5957.

- Augais, A. and Hazet, P., 2022. Artisanal craft profession: The indispensable guide to developing its activity. Paris: Eyrolles edition, 2022. ISBN: 2416004883.

- Bédard, M., 2016. Entrepreneurship and economic freedom: An analysis of empirical studies. Canada: Montreal Economic Institute, 2016. ISBN 978-2-922687-68-2.

- Boillat, P., 2007. From mobility to sustainable mobility: Urban transport policies, University of Geneva Mobility Observatory. 2007.

- Boutillier, S., 2017. Entrepreneurship and innovation: Contexts and concepts. In: Revue internationale PME. 2017, 31(2), 201-203. ISSN 1918-9699.

- Chantelot, CS., 2009. The thesis of the „creative class“: Between limits and developments. In: Geography, Economy, Society. 2009, 411. Available at: <https://doi:1111/j.1944-8287.2009.01046.x>

- Colbert, F., 2007. Marketing of arts and culture. Canada: Gaëtan Morin edition, 2007. ISBN: 978-2-76504-527-4.

- Crevoisier, O., 2001. The approach through innovative environments: state of the art and perspectives. In: Regional and Urban Economics Review. 2001, 1. ISSN 0180-7307.

- Decree No. 96-01 of 19 Chaâbane 1416 corresponding to January 10, 1996 laying down the rules governing handicrafts and trades (Official Journal No. 3 – 1996).

- Diedrich, M., 2022. Sustainability integration and communication in German manufacturers. In: Marketing Science & Inspirations. 2022. 17(2), 2-15. ISSN 1338-7944.

- Bourgeon-Renault, D., 2009. Marketing of art and culture. Paris: Dunod edition, 2009. ISBN 978-2100505821.

- Donsimoni, M. and Perret, C., 2008. Social capital and territorial development: The case of two Wilayate ensembles of Kabylie. In: International Conference on Local Development and Governance, University of Jijel, Algeria.

- Eckert, D. and Grossetti, M. and Martin-Brelot H., 2012. The creative class to the rescue of cities. In: The Life of Ideas. 2012. ISSN 2105-3030.

- Florida, R., 2005. Cities and the creative class. London: Routledge, 2005. ISBN 9780203997673.

- Florida, R., 2003. The rise of the creative class and how it’s transforming work, leisure and everyday life. New York: Basic Books, 2003. Available at: <https://doi:2307/3552294>

- Information dossier, No. 5, entitled „Intellectual property and traditional crafts“, 2016, World Intellectual Property Organization, Geneva.

- Kaci, A. and Amiar, L., 2022. Analysis of the territorial conditions for setting up an agro-logistics beverage cluster: As a tool for territorial attractiveness in the wilaya of Bejaia. In: Economic Studies and Research Journal. 2022, 6(1). ISSN 2676-1580.

- Laoudj, O. and Munoz, M. 2023, Tools for improving Algerian craftsmanship through value chain analysis and other competitive advantages. Ridart study, Algerian Ministry of Tourism and Craftsmanship, Algeria, 2023.

- Laoudj, O., 2016. Sources of knowledge in the value chain of traditional craftsmanship. Ed. Pr. Abdelkader Djeflat: The integration of knowledge and innovation in the global south. France: L’Harmattan Publishing, 2016. ISBN

- Lefèvre, B., 2019. Cultural industries and creative economy: What models for the territoriality of creation. In: Open Edition Journals. 2019, 36(1). ISSN 1920-7344. Available at: <https://doi:4000/communication.9965>

- Loudiyi, S., Angeon, V. and Lardon, S., 2004. Social capital and territorial development: What spatial impact of social relations? Conference: Colloque ESO. 2004.

- Perret, C., 2010. Social capital and business nuclei in Algeria, In: Development Worlds. 2010, 149(1), 105-116. ISSN 0305-750x.

- Perret, C. and Chibani, A., 2010. The experience of the nucleus approach and the evolution of the role of the Algerian Chamber of Crafts and Trades (CAM). In: Vulnerability, Equity and Creativity in the Mediterranean. Sustainable Development and Mediterranean Territories Pole, France, 2010.

- Philippe, C., 2009. Technical advisor DEVED, innovative microfinance pilot experience in Ghardaia; GTZ Algeria. National Conference on Crafts and Trades, November 2009.

- Poinsignon, P., 2022. Renewing creation: The emergence of artistic movements in creative industries. PhD thesis of the Polytechnic Institute of Paris, 2022.

- Roy-Valex, M. and Bellavance, G., 2015. Arts and territories in the era of sustainable development: Towards a new cultural economy. Canada: Presses de l’Université Laval, 2015. ISBN 978-2-7637-2619-9.

- Tremblay, D. G., 2010. The creative class according to Richard Florida. France: Rennes University Press, 2010. ISBN978-2-7535-1143-9.

- Tremblay, D. G. and Darchen, S., 2008. The innovative environment and the creative class. Canada: Research Note No. 2008-01, Canada Research Chair on Socio-Organizational Issues in the Knowledge Economy, University of Quebec, Montreal, Canada.

- United Nations report entitled „Perspectives on the creative economy 2022“. United Nations Conference on Trade and Development: Geneva, 2022.

- Kerr, W. R. and Nicoud, R. F., 2019. Tech clusters. Working Paper No. 20-063. Harvard Business School, 2019. [online]. [cit. 2024-04-10]. Available at: <https://www.hbs.edu/ris/Publication%20Files/20-063_97e5ef89-c027-4e95-a462-21238104e0c8.pdf>

- Yagoubi, A. and Tremblay, D. G., 2017. Uncertain creative worlds: challenges of trajectories, projects and strategies. In: Culture, Careers and Creative Industries. 2018, 57, 2-10. ISSN 1710-7377.

Kľúčové slová/Key words

cluster approach, innovation, artistic crafts, creative economy, Algeria, 3Ts model

klastrový prístup, inovácie, umelecké remeslá, kreatívne hospodárstvo, Alžírsko, model 3Ts

JEL klasifikácia/JEL Classification

M31, O34

Résumé

Podpora inovácií v alžírskych remeslách: Vplyv rozvoja klastrov v provincii Constantine a Batna

Tento článok sa zaoberá klastrovým prístupom ako pákou na stimuláciu inovácií a podnikania v sektore remesiel v Alžírsku, pričom sa konkrétne zameriava na klastre remeselníkov pracujúcich s mosadzou v Constantine a remeselníkov klenotníctva v Batne, dvoch provinciách v Alžírsku. Na základe modelu „3T“ Richarda Floridu (technológia, talent a tolerancia) štúdia analyzuje, ako môže príslušnosť ku klastru umožniť remeselníkom získať inovačné schopnosti a realizovať kolektívne projekty.

Metodikou použitou v tomto výskume je terénny prieskum uskutočnený počas 21. medzinárodného veľtrhu tradičných remesiel v Alžírsku. Vzorku tvorí 228 remeselníkov, ktorí predstavujú 30% účastníkov veľtrhu, s rozdelením 46% žien a 54% mužov. Údaje sa zbierali pomocou štruktúrovaného dotazníka založeného na troch kľúčových inovačných faktoroch definovaných modelom „3T“. Údaje boli následne analyzované pomocou deskriptívnej analýzy a krížových tabuliek.

Výsledky naznačujú, že hoci remeselníci zostávajú viazaní na tradičné metódy, uvedomujú si dôležitosť inovácií pri zachovávaní a propagácii svojich remesiel. Osvojenie informačných a komunikačných technológií je však obmedzené, čo poukazuje na potrebu intenzívnejšej odbornej prípravy. Štúdia tiež poukazuje na potenciál klastrov posilniť spoluprácu medzi remeselníkmi, uľahčiť výmenu poznatkov a zlepšiť ich konkurencieschopnosť na globálnom trhu. V závere článku sa zdôrazňuje význam ochrany remeselnej tvorivosti prostredníctvom kolektívnych značiek a zemepisných označení.

Recenzované/Reviewed

22. April 2024 / 22. May 2024