1 Introduction

Mobile telephony occupies a central place in the economic and social sphere in Algeria, and its use is increasingly essential for both individuals and businesses. The ease with which you can take a photo, make a call, watch a film, place an order or advertise are just some of the reasons why mobile telephony has become an integral part of people’s everyday lives.

One of the most striking changes of the last millennium has been the integration of the mobile phone into everyday life, to the point where its indispensability has become indisputable. This phenomenon has affected all generations: baby-boomers, X, Y and Z, but the most enslaved is generation Z, followed by generation Alpha. The Algerian consumer is not to be outdone, in the sense that it has affected all social strata and all generations, becoming the communication and interpersonal tool par excellence.

Part of our survey, we focused on a population that is over-consuming ICTs but has no economic capital for the product acquisition process: the young consumer.

This article examines young consumers using data from a survey we carried out, from the perspective of uses and preferences. It is in this context that we look at how young people use smartphones.

The aim of this article is to understand how young Algerian consumers of mobile telephony behave, particularly in terms of loyalty or switching operators, the attractiveness of commercial offers, consumption patterns (usage); and secondly, to measure the level of appreciation of the quality of operators’ services, promotional offers, the most commonly used chips (operator), mobile internet, the quality of connectivity, network coverage and the income spent on charges and/or the budgets devoted to mobile telephony. The aim is to draw up a clear picture of the different dimensions that make up the mobile telephony market in Algeria among young people and the different uses they make of it.

2 Literature review

Digital natives have grown up with smartphones and are among the earliest adopters of these technologies. They often see their mobile phone as an extension of themselves and use it for a variety of activities, including communication, social networking, gaming and accessing information (Lenhart 2015; Boyd 2014; Rosen, Carrier and Cheever 2013).

Indeed, the growth in smartphone penetration among young people has become ubiquitous, with a sharp increase in ownership of these devices (Anderson et al. 2015; Rideout 2015; Twenge 2019; Elhai et al. 2017). The ease of access to the internet and mobile applications has led to rapid adoption of smartphones among young consumers (Anderson et al. 2015).

Understanding these behaviours seemed relevant to us from the perspective of the uses and gratifications model approach, which recognises the receiver’s own counter-power, punctuated by „needs“, „expectations“, „uses“ and „gratifications“ (Stafford and Stafford 2003; Stafford, Stafford and Schkade 2004; Parker and Plank 2000; Mukherji and Nicovitch 1998) and gives pride of place to the study of social media by focusing on the user as the central actor (Shao 2009; Papacharissi and Mendelson 2011). For more than two decades, researchers have shown a growing interest in the motivations linked to Internet use (Kaye 2010). This approach has been used to explore different domains, such as the Internet itself (Stafford and Stafford 2003; Stafford, Stafford and Schkade 2004; Parker and Plank 2000; Mukherji and Nicovitch 1998), which have made it possible to identify four categories: surveillance, distraction/entertainment, personal identification and social relations (Blumer and Brow 1972; Rubin 2000).

Other studies point out (Wang, Tchernev and Solloway 2012; Dhir et al. 2018) that social needs are the main motivation for young people to use social media, but that they do not necessarily experience social gratification by using them, but rather to satisfy emotional and cognitive needs. Work by lenhart (2015) suggests that teenagers are heavy consumers of social media because they own smartphones and spend a lot of time online (Marcus 2018) Social media represent a means of communication and social connection for young people. Lenhart (2015) highlights significant gender differences in social media use: girls are more likely to share personal content, while boys are more likely to play online games.

Twenge (2017, 2019) argues that young people face unique challenges due to their reliance on electronic devices, particularly smartphones, and their extensive use of social media, which have led to notable changes in young people’s behaviour, including a lack of autonomy, the promotion of conformity and self-censorship, making them less prepared for adult life as a result of these trends. In addition, research by Przybylski et al. (2019) suggests that excessive use of digital media may be associated with decreased psychological well-being in adolescents, mainly on social networks (Facebook, Twitter and Instagram).

2.1 Description of the mobile telephony market in Algeria

Over the last twenty years, the telecommunications sector in Algeria has undergone a number of changes which have contributed to its development, in particular through the establishment of the regulator (ARPCE 2023), the introduction of new operators and the granting of licenses.

Following the adoption of law no. 03/2000 of 05/08/2000, the telecoms sector underwent an in-depth reform. This reform encouraged the development of the sector in a competitive environment, ensuring the competitiveness and diversification of the Algerian economy.

The mobile telephony market in Algeria is an oligopoly, with only three operators currently sharing the market (see Table 1): the incumbent public operator, Algérie Télécom via its subsidiary Algeria Telecom Mobile (ATM), „MOBILIS“ since 2003, Optimum Telecom Algeria (OTA), „DJEZZY“ since 2001 and Wataniya Telecom Algeria (WTA), „OOREDOO“ since 2004.

| 4th quarter 2021 | 1st quarter 2021 | 2nd quarter 2022 | 3rd quarter 2022 | 4th quarter 2022 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Algeria Telecom Mobile | 19 829 935 | 20 304 274 | 20 367 866 | 20 782 507 | 21 098 772 |

| Optimum Telecom Algérie | 14 593 618 | 14 661 938 | 14 672 436 | 14 994 977 | 15 177 875 |

| Wataniya Telecom Algérie | 12 592 204 | 12 705 272 | 12 624 923 | 12 727 217 | 12 742 119 |

| Total | 47 015 757 | 47 671 484 | 47 665 225 | 48 504 701 | 49 018 766 |

Table 1: The mobile telephony (number of subscribers)

Source: ARPCE (consulted on 23/04/2023 at 14:27)

The mobile telephony market in Algeria is growing and evolving. According to the most recent data, the sector’s growth rate (from Q4 2021 to Q4 2022) is 4.26%, rising from 47 million subscribers in 2021 to 49 million subscribers in 2022. Add to this the penetration rate, which recorded a net increase of 4. 34 points between the 4th quarter of 2021 (106.71%) and the 4th quarter of 2022 (111.05%), this development is due to the slight increase in the mobile telephony market on the one hand and the Algerian population on the other (ARPCE 2022).

2.2 Breakdown by type of subscription

The mobile telephony market is divided into the postpaid and prepaid markets.

- Postpaid is „a concept used to describe a telephone or television service that is paid for at the end of the month”.

- Prepaid is „payment made before the time credit is used up, and for a fixed period”.

| 2021 | 2022 | |

|---|---|---|

| Mobilis | 19117798 | 20391988 |

| Djezzy | 13823125 | 14383943 |

| Ooredoo | 11462459 | 11613170 |

| Total | 44403382 | 46389101 |

Table 2: Number of subscribers

Source: ARPCE (consulted on 23/04/2023 at 17:27)

The number of prepaid subscribers is higher than the number of post-paid subscribers. If we compare the two tables, we can see that subscribers are increasingly opting for the prepaid formula.

In conclusion, Algeria is the second largest consumer market in North Africa in the telecoms sector (www.veon.com consulted on 23/04/2023 at 5.45pm). Nowadays, many people own a Smartphone, and the mobile phone market in Algeria is also characterized by strong demand for Smartphones. Because of this high demand, mobile operators are offering unlimited mobile data packages and affordable handsets to attract new customers. However, the mobile sector in Algeria is facing challenges such as poor network coverage in some parts of the country and increased competition between operators. Despite this, the market continues to grow and evolve to meet the mobile communication needs of Algerian consumers.

3 Methodology

In order to gain a better understanding of the mobile telephony usage practices of young Algerians, it is essential to understand their consumption habits and expectations (Noui and Abedou 2016). With this in mind, a national survey based on questionnaires distributed to households was carried out, involving two profiles within the same household: on the one hand, young people under the age of 18 and, on the other, adults aged 18 and over.

The main objective of this survey was to focus on young Algerians, by gathering their opinions and behaviour regarding the use of telecommunications. It should be noted that the young people questioned were interviewed in the presence and with the prior permission of their parents.

The sample used in this study was selected from the parent population, i.e. Algerian households, according to data from the last national census in 2008. The recommended sample for this study consisted of 800 households from 15 regions of Algeria.

The questionnaire distributed to the 800 households was organised into several sections, including identification of the household, characteristics of the household members, details of the dwelling, and characteristics of the respondents, both adults and young people.

The questionnaire distributed to the 800 households is structured under the following headings:

• Household identification

• Characteristics of household members

• Characteristics of the dwelling

• Characteristics of respondent I (+18 years old)

• Characteristics of respondent II (under 17)

To guarantee the reliability and usefulness of the information gathered, methodological precautions were taken. For example, with regard to the geographical distribution of the households surveyed, it was stipulated that at least 70% of households should belong to urban areas and 30% to rural areas, in line with the demographic distribution characteristics according to the national census. In addition, the third part of the questionnaire, dealing with the characteristics of the respondents within the household, had to be completed by two individuals: one adult aged between 18 and 99 and one young person under 18, in order to ensure a balanced representation of the different age groups within each household.

To ensure the accuracy of the information collected from children, specific measures were taken in the design and administration of the household questionnaires. The questionnaires were adapted to children’s level of understanding, with simple, clear questions. A separate section of the questionnaire was dedicated to them, addressing their habits and expectations regarding the use of mobile phones. The children were interviewed in the presence and with the permission of their parents, ensuring an ethical and secure environment. The confidentiality and anonymity of their answers were guaranteed to encourage free and honest expression. In addition, the language used was adapted to their age to facilitate understanding (Noui and Abedou 2016; Bouslah and Djebbouri 2022).

The sampling method used in this study is a combination of stratified and cluster sampling (China 2011). Stratified sampling was used to identify the 15 wilayas of Algeria (the strata) to ensure a diverse geographical representation. This stratification makes it possible to take account of regional variations in mobile phone usage patterns and to obtain nationally representative results. The cluster sampling method was used to form clusters of households. A cluster here refers to a group of households that are geographically close to each other. The clusters were selected randomly to avoid selection bias (China 2011). This cluster sampling method reduces data collection costs by grouping households located in close geographical areas. The households interviewed were selected at random from the clusters selected in each region. In this way, each household had an equal chance of being included in the sample.

Map 1: Spatial distribution of the survey sample (young consumers)

Source: Authors according to survey data

4 Results

According to the results of the table below (see Table 3), there were total of 800 respondents in the 6-18 age groups. For methodological reasons, we have divided the sample into three age ranges.

4.1 The sample structure

| Age of resopndents | Gender (%) | No of phone (%) | No of phone chip (%) | Operator (%) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age group | % | Male | Female | One | Two | One | Two | Mobilis | Ooredoo | Djezzy |

| 6-11 | 11 | 53 | 47 | 11 | 0 | 11 | 0 | 35.0 | 44.6 | 20.0 |

| 12-15 | 43 | 48 | 52 | 43 | 25 | 43 | 25 | 27.1 | 52.2 | 26.1 |

| 16-18 | 45 | 44 | 56 | 45 | 75 | 45 | 75 | 15.4 | 46.2 | 38.5 |

Table 3: Statistical summary of survey respondents

Source: Authors based on SPSS outputs

The first age group is between 6 to 11 years, corresponding to childhood and the primary school age group, the second is between 12 and 15 years of age, the teenage years when the entire population begins its transition from primary to secondary school. This age group is identified as an unstructured population, operating on the basis of mimicry, hence a consumption pattern converging towards the collective. It is a group in search of an identity. The third age group is the 16-18 year olds, the majority of whom are at secondary school. Unlike the previous category, this is a population that tends to differentiate itself and assert its identity. As a result, our population is made up as follows: 6-11 years old: 11.1%; 12-15 years old: 42.1% and 16-18 years old: 44.3.

The survey sample is broken down by gender and age category as follows: the 6-11 age group is made up of 53% boys and 46% girls, the 12-15 age group is made up of 48% boys and 51% girls, and the 16-18 age group is made up of 44% boys and 55% girls. The 16-18 age groups are made up of 44% boys and 55% girls. This relatively homogenous structure (male/female) reproduces the structure of the Algerian population, according to the National Statistics Office ONS data;

The arrival of technology in Algerian families is part of a process of social change in parental practices. In our sample, we found that mobile phone ownership starts at the age of 6, and we believe that this acquisition is part of a process of recycling parents’ phones. However, for the second age group, we are dealing with a category of young adolescents who are still dependent but who are seeking autonomy by owning an individual object in order to stand out socially. Nevertheless, this acquisition is obviously made with the approval of the parents, who are responding to a utilitarian approach, by offering themselves assurance and undeniable social control over their children. For adolescents, this acquisition is a response to social normality, a vector of autonomy in relation to parents. We also note that the number of chips suitable for children is limited to one, which supports the previous idea that children use mobile phones as a result of recycling by their parents. On the other hand, for the other two age groups we are seeing a change in the number of phone chips acquired, and this trend is more pronounced in the third age group.

This change in the number of chips acquired follows a logical pattern in the transformation of the social use of the telephone (chips). The first chip acquired was because parents wanted to equip their children with a telephone line so that they could be contacted, but the second chip must correspond either to the construction of new extra-familial sociabilities or for reasons of more attractive commercial offers.

Given the affinity of the younger generation for social networks, video streaming, and gaming, the results for the choice of current operator converge towards the same logic. In this sense, the first criterion for choosing or keeping an operator is better connectivity for the three age categories, which rightly leads to the preferred choice of usage, followed by the criterion of ‘attractive offers’ (voice and data), by which we mean the ability to have a product that meets the optimum conditions at a lower acquisition cost.

For all three age categories, connectivity remains the key factor in the choice of operator. The choice of connectivity and more attractive commercial offers may be determining factors in the volatility of this category of consumers. Indeed, young people may migrate from one operator to another if better commercial and technical offers become available.

4.2 Mobile phone uses

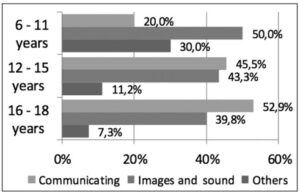

Initially, the mobile phone was intended as part of a communications system designed to transmit and receive the „human voice“, enabling people to make phone calls anywhere. With the advent of the internet, the mobile phone now serves a dual purpose: making phone calls and accessing the internet. At present, mobile phones are used for a trilogy of purposes: communicating, viewing images and listening to sound (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Mobile phone uses

Source: Authors elaboration based on young survey on young survey 2023 outputs

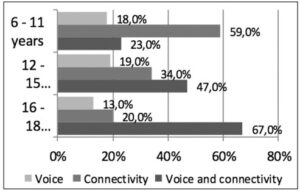

Figure 2: Frequency of phone uses

Source: Authors elaboration based on young survey on young survey 2023 outputs

Initially, the mobile phone was intended as part of a communications system designed to transmit and receive the „human voice“, enabling people to make phone calls anywhere. With the advent of the internet, the mobile phone now serves a dual purpose: making phone calls and accessing the internet. At present, mobile phones are used for a trilogy of purposes: communicating, viewing images and listening to sound.

For our sample, the initial use of the mobile phone, which is conversational, remains unchanged for the last two age groups and to a much lesser extent for children (aged 6-11). On the other hand, the primary use made by children is likened to the extension of television use through downloading and viewing videos, plus video games.

The 12-15 age groups is following the same trend as children, using their mobile phones as an extension of audiovisual activities, but in addition to communication via social networks. This need to interact via social networks becomes more pronounced in the third category (16-18 year olds). Adolescence is a period of life when the need to interact and communicate is crucial, and the data collected confirms this for the 16-18 year olds. Uses are mainly oriented towards the trilogy: listening to music online, watching videos and using social networks.

The least common use, which could have been dominant for this age group given that most of them attend school, is documentary research, which is absent from young people’s uses. As a result, these two age groups stand out for their use of voice and data, as part of a strategy to build new social.

4.3 Consumption limits

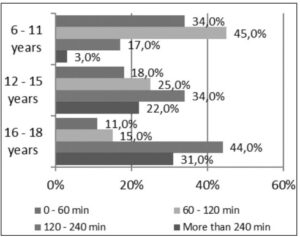

As per the figure below, telephone uses remains minimal for all age groups, with the majority of respondents spending between 0 and 10 minutes on voice calls. It can be argued that this minimum time spent on voice is utilitarian (calls to parents to report delays, unforeseen events, etc.).

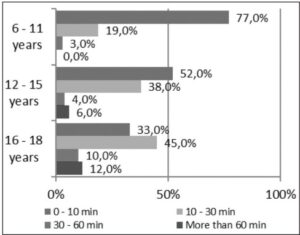

Figure 3: Mobile phone consumption

Source: Authors elaboration based on young survey on young survey 2023 outputs

Figure 4: Frequency of consumption

Source: Authors elaboration based on young survey on young survey 2023 outputs

The second interval is between 10 and 30 minutes, when the majority of calls are made by 16-18 year olds. In this sense, the quest for new social activities for young adults involves telephone conversations, which may be moderate, but when added to the time interval devoted to data, this age group over-consumes all the functions of the telephone (voice and data).

Data usage is indeed prevalent, yet its utilization remains relatively low among children aged 6 to 11 during both time intervals of (0-60 minutes) and (60-120 minutes). On the other hand, data consumption is confirmed in the second age category, where the number of hours connected is almost equivalent for the four time bands, broken down as follows: 0-60 minutes: 47%, 60-120 minutes: 49%, 120-240 minutes: 41%, more than 240 minutes: 40%. On the other hand, young adults (aged 16-18) are essentially in the maximum time frame, in fact, 54% of 16-18 years old.

Nevertheless, the breakdown of consumption by gender shows that girls are predominantly in the lower timeframes. However, boys are positioned in terms of data consumption in the most excessive timeframes (+240 minutes/day).

As part of this new form of digital parenting, we highlight the budget spent by parents on topping up their children’s phones, which averages between DZD 100 and DZD 500 per month (see Figure 5).

Figure 5: Reloading by age interval

Source: Authors based on Young survey (2023)

The graph above validates a consistent budget falling within the range of DZD 100 to DZD 499 across the three age groups and three mobile operators. Notably, this budget range strongly characterizes the spending pattern of 12-15 year-olds. The graph also indicates a shift in age categories as the budget increases. Specifically, amounts between 100 and 499 DZD predominantly apply to 12-15 year-olds, whereas sums of 500 DZD or more are allocated to the 16-18 year-old category.

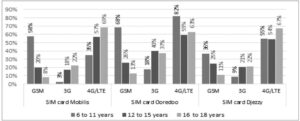

It is worth mentioning that the acquisition of 4G is widespread across chip purchases from Mobilis, Ooredoo, and Djezzy for all age categories in our sample (refer to Figure 6). Nevertheless, a significant portion of subscribers, especially with Ooredoo, appears to still be on 3G plans. This tendency could be attributed to the potential absence of 4G coverage in certain regions.

Figure 6: Appropriation of technology by young people

Source: Authors based on Young survey (2023)

5 Synthesis

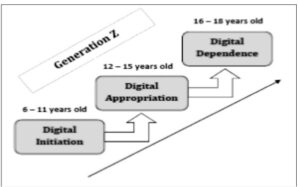

The survey findings among young people (Generation Z) indicate that the specified age groups are not conflicting but rather represent stages or phases in the life cycle of youth, encompassing the transition from childhood to young adulthood. The results illustrate that all participants went through initial phases of engagement, typically between the ages of 6 to 11, followed by a subsequent stage (12-15 years) characterized by heightened usage of mobile telephony (both voice & data) involving extended digital activities and a broadening array of applications (such as Facebook and phone usage). The third age category (16-18 years old) signifies an increased intensity or enthusiasm in digital behavior.

To achieve this goal, we have outlined the typical consumer profiles within the mentioned categories as follows:

Digital Initiation Phase

Target Audience: Children aged 6 to 11 years old.

Description: in this phase, children are provided with a mobile phone to ensure accessibility by their parents. They primarily use data for activities such as watching videos and playing games.

Digital Appropriation Phase

Target Audience: Adolescents aged 12 to 15 years old.

Description: during this phase, adolescents exhibit more pronounced behaviors compared to the previous category. They engage in extensive and diverse use of mobile telephony, incorporating both voice and data, with a focus on more extended periods of usage.

Digital Dependence Phase

Target Audience: Young adults aged 16 to 18 years old.

Description: this phase comprises young adults characterized by conscientious digital behavior. They demonstrate a high level of dependence, with internet connection times exceeding four hours per day, indicating a significant reliance on digital technology.

The examination and interpretation of data collected from a survey of individuals under the age of 18 revealed key insights organized into a typology. This typology is designed around three primary user profiles for mobile telephony, encompassing both (Voice and Data) usage.

Figure 7: User profiles on the mobile phone (Voice & Data)

Source: Authors based on Young survey (2023)

The table below sets out the main characteristics of young Algerian mobile phone consumers and the actions and guidelines that have resulted.

| Consumption phase (Voice & Data) | Age & generation | Features | Actions{Orientations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Digital initiation phase | 6-11 years (Z) child | - Latent potential age range - Possession of a mobile phone is from the age of 6 - Parents partially control consumption (voice and data) | Marketing and communication strategy oriented towards parents with an emphasis on the reachability of children + location technology |

| Digital appropriation phase | 12-15 years (Z) pre-post adolescent | - Potential age range (target population) - Consumption of social relationships - Having a small budget dedicated to mobile telephony | A mixed marketing and communication strategy oriented towards both pre-post adolescents and parents: attractiveness of the data offer |

| Digital addiction phase | 16-18 years (Z) young adult | - Potential age group (target population) - Having a small budget dedicated to mobile telephony - Preference for 4G - Hyper-connected age group - Greater voice consumption than other generation Z age groups | Strategy of targeting young people with offers oriented towards more data broken down in terms |

Table 4: Strategic orientations based on the results of the survey

Source: Authors based on SPSS outputs

6 Conclusion

A rallying tool, a socialising tool, a versatile instrument for interacting with others, the smartphone creates links and enables people to become part of a group and a system of virtual relationships. In addition to its many advantages for searching, encoding information, broadcasting messages, recording images, learning, remote control, etc., the smartphone enables its user to take his or her network of relationships anywhere and at any time. This article also highlights the complexity of the relationships between young people and their smartphones, highlighting a diverse range of uses that reflect the multifunctional nature of these devices.

However, despite these advantages, the negative implications cannot be overlooked. Growing concerns about the impact on young people’s mental health of excessive smartphone use highlight the urgent need for collective reflection on managing the balance between online and offline life. Screen addiction, diminished attention spans and social isolation are all challenges facing society.

Literatúra/List of References

- Anderson, M. and Jiang, J., 2018. Teens, social media & technology 2018. Pew Research Center. 2018. [online]. [cit. 2023-12-05]. Available at: <https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/wp-content/uploads/sites/9/2018/05/PI_2018.05.31_TeensTech_FINAL.pdf>

- Boyd, D., 2014. It’s complicated: The social lives of networked teens. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0300166316.

- Blumer, J. G. and Brow, B. J., 1972. Uses and gratifications of television news and their relation to news preference. In: Journalism Quarterly. 1972, 49(2), 299-305. ISSN 0022-5533.

- Bouslah, M. A. and Djebbouri, M., 2022. An applied study to measure the impact of mobile service quality on customer satisfaction using structural equations (case of Algeria. In: Economic review El bachair. 2022, 8(1), 968-988. ISSN 1112-7201.

- Chine, L., 2011. Methodology of Algerian employment surveys. In: Economic studies review. 2011, 5(3), 325-332. ISSN 2507-7597.

- Diedrich, M., 2018. Everyday internet use. How do end users use the mobile internet? In: Marketing Science & Inspirations. 2018, 13(1), 21-29. ISSN 1338-7944.

- Dhir, A., Chen, S. and Nieminen, M., 2018. Predicting adolescent problematic online gaming using teacher ratings of student behavior and motivations for playing. In: Computers in Human Behavior. 2018, 78, 10-17. ISSN 0747-5632.

- Elhai, J. D., Levine, J. C., Hall, B. J. and Hall, B. J., 2017. Fear of missing out, need for touch, anxiety and depression are related to problematic smartphone use. In. Computers in Human Behavior. 2017, 69, 75-81. ISSN 0747-5632.

- Kaye, B. K., 2010. It’s a numbers game: Self-esteem regulation, emotional distress, and social network site user behavior. In: Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication. 2010, 15(1), 144-154. ISSN 1083-6101.

- Lenhart, A., 2015. Teens, social media & technology overview 2015. Pew Research Center. 2015. [online]. [cit. 2023-12-05]. Available at: <https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2015/04/09/teens-social-media-technology-2015/>

- Mukherji, J., Mukherji, A. and Nicovich, S., 1998. Understanding dependency & use of the Internet: a uses & gratifications perspective. In: American Marketing Association. 1998, 31, 198-213. ISSN 0022-2437.

- Noui, R. and Abdou, A., 2016. Mobile telephony in Algeria: non-economic factors and the social embedding of operator choice. In: Annals of Social and Human Sciences. 2016, 16, 1-16. ISSN 1112-7880.

- Papacharissi, Z. and Mendelson, A. L., 2011. Toward a new(er) sociability: Uses, gratifications, and social capital on Facebook. In: S. Papathanassopoulos (Ed.), Media perspectives for the 21st century. Routledge, 2011, pp. 212-230. ISBN 978-0-415-78052-6.

- Papacharissi, Z. and Rubin, A. M., 2000. Predictors of internet use. In: Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media. 2000, 44(2), 175-196. ISSN 0883-8151.

- Parker, R. S. and Plank, R. E., 2000. A uses and gratifications perspective on the Internet as a new information source. In: American Business Review. 2000, 18(2), 43-49. ISSN 0889-4419.

- Przybylski, A. K., Orben, A. and Weinstein, N., 2019. Are associations between „screen time” and lower psychological well-being robust across national contexts? Evidence from three large-scale datasets. In: Psychological Science. 2019, 30(7), 987-1008. ISSN 0956-7976.

- Report Mobile „Market Report”. Regulatory Authority for the Post Office and Electronic Communications. 2023. [online]. [cit. 2023-12-05]. Available at: <https://www.arpce.dz/fr/doc/raa>

- Rosen, L. D., Carrier, L. M. and Cheever, N. A., 2013. Facebook and texting made me do it: Media-induced task-switching while studying. In: Computers in Human Behavior. 2013, 29(3), 948-958. ISSN 0747-5632.

- Rideout, V. J., 2015. The common sense census: Media use by tweens and teens. Common Sense Media, 2015. ISBN 978-0-9981943-0-2.

- Stafford, T. F. and Stafford, M. R., 2003. Identifying motivations for consumer web site loyalty. In: Journal of Strategic Marketing. 2003, 11(3), 155-169. ISSN 0965-254X.

- Stafford, T., Royne, M. and Schkade, L., 2004. Determining uses and gratifications for the internet. In: Decision Sciences. 2004, 35, 259-288. ISSN 0011-7315.

- Shao, G., 2009. Understanding the appeal of user-generated media: A uses and gratification perspective. In: Internet Research. 2009, 19(1), 7-25. ISSN 1066-2243.

- Twenge, J. M., 2017. iGen: Why today’s super-connected kids are growing up less rebellious, more tolerant, less happy and completely unprepared for adulthood and what that means for the rest of us. Atria Books, 2017. ISBN 978-1501151989.

- Wang, S. S., Tchernev, J. M. and Solloway, T., 2012. A dynamic longitudinal examination of social media use, needs, and gratifications among college students. In: Computers in Human Behavior. 2012, 28(5), 1829-1839. ISSN 0747-5632.

Kľúčové slová/Key words

young people, approach to usage, smartphone, social networks

mladí ľudia, prístup k používaniu, smartfón, sociálne siete

JEL klasifikácia/JEL Classification

M31, Z13

Résumé

Používanie smartfónov medzi mladými ľuďmi

Cieľom tohto článku je pochopiť fenomén nadobúdania a používania smartfónov mladými Alžírčanmi, a to pomocou prístupu založeného na modeli používania a uspokojovania a so zameraním na používateľa ako hlavného aktéra. Za týmto účelom sme sa zamerali na kategóriu mladých spotrebiteľov, pričom vzorka bola z hľadiska veku rôznorodá. Cieľom je identifikovať úroveň penetrácie smartfónmi u mladých spotrebiteľov; identifikovať spôsoby, akými získavajú a používajú smartfóny; a napokon identifikovať perspektívy zmien v spôsoboch ich používania (očakávaní). Odporúčanú vzorku pre túto štúdiu tvorí 800 mladých spotrebiteľov z rôznych štátov Alžírska. Tento článok poukazuje na zložitosť vzťahu medzi mladými ľuďmi a ich smartfónmi, pričom vyzdvihuje rôznorodé spôsoby používania, ktoré odrážajú multifunkčný charakter týchto zariadení.

Recenzované/Reviewed

10. February 2024 / 12. March 2024