With more than 70% of the world being religious, there is an urgent need for better understanding the relationship between religion and consumer behavior. The aim of this study is to analyze the purchase behavior of an air purifier for religious and non-religious consumers. This has been accomplished through 23 qualitative interviews using the mobile instant messaging interview method (MIMI). Using thematic and sentiment analysis, important themes were identified such as the pandemic, religion but also sentiments and purchase behavior patterns of an air purifier. Moreover, subtle nuances regarding the consumer behavior of the religious individual were discovered, such as frugality and the power of religious communities. Henceforth, this work has contributed to both academia and management, by analyzing different aspects of the relationship between religion and consumer behavior, using in depth qualitative methods.

Introduction

This paper has the goal of analyzing certain aspects of the relationship between religion and consumer behavior all in the final battle of the Covid pandemic in Romania. Religion can be considered one of the most important aspects of society, since more than 70% of individuals in the world are religiously affiliated (Pew Research Center 2017). Moreover, it is estimated that by 2050, the number of people religiously unaffiliated will drop to 13% (from 16% in 2010), according to Lipka (2015). Also, Pew Research Center (2017) estimates that by 2060, the world population will grow by 32%, reaching almost 9.6 billion people. Among these, Muslims are expected to grow by more than 70% since they have very high fertility rates. These numbers and predictions are a testimony of the magnitude of organized religion in the world.

But what exactly is religion, and can it even be defined? Oxtoby and Hussain (2010, 175) define it as a „sense of power beyond the human, apprehended rationally as well as emotionally, appreciated corporately as well as individually, celebrated ritually and symbolically as well as discursively, transmitted as a tradition in conventionalized forms and formulations that offers people an interpretation of experience, a guide to conduct, and an orientation to meaning and purpose in the world“. Regarding consumer behavior, a sub-discipline of marketing with overarching influences in many areas such as psychology, economics, sociology and many more, Hawkins and Mothersbaugh (2010) define it as the study of individuals, groups, or organizations and the processes they use to select, obtain, use, and disperse products, services, experiences, or ideas to satisfy needs and the impact these processes have on the consumer and society. Two fields at first sight unrelated, but with a common denominator, the individual. Is there a connection between the two?

Many authors argue that there is. For example, the impact of religion on the economy can take many forms, one of which is the macro and micromarketing one. From a macro marketing view, religion can influence what, how, when, and where certain market transactions take place. For example, religion may prohibit or encourage the sale of certain products (e.g. banning alcohol or encouraging the use of certain products at certain times, such as eggs on Easter in selected countries) or limit when a product can be sold, like on certain holy days (Mittelstaedt 2002). From a micro perspective, religion influences an individual’s core values, which in turn will influence certain aspects of consumer behavior (Kahle 1996; Minton and Kahle 2013; Kahle and Valette-Florence 2012; Hirschman 1983).

Other authors (Rinallo, Scott and Maclaran 2012; Minton and Kahle 2013) identified different interactions between religion and the marketplace such as: (1) the sacralization of the mundane (e.g., classic wine becomes sacred in some Christian traditions), (2) spiritual meanings assigned to consumption (e.g. collecting religious objects), (3) the commercialization of the spiritual (e.g. marketing of religious services, religious tourism), (4) consumption of spiritual goods (e.g. icons or statues of Buddha), and (5) adaptation to the sacred, which describes how businesses and politicians change practices and regulations to better serve religious consumers.

Minton and Kahle (2016) identified specific areas that interact and are influenced by religion. Ethics is one of the most intense studied fields of the relationship between religion and consumer behavior, largely because most of the world’s religions have as a central part of their scriptures and teachings prescriptions and prohibitions related to the ethical behavior of adherents (e.g., don’t steal, don’t kill, don’t lie, etc.). General shopping behavior is another area of influence of religion. For example, studies identified that Jewish consumers were more innovative and more likely to be opinion leaders compared to Catholic, Protestant, Hindu, Muslim or Buddhist consumers (Hirschman 1981). Other studies by Shachar et al. (2011) discovered that the more religious consumers are, the less likely they are to seek out branded products that contribute to self-esteem. Other researchers have identified differences related to product price, with highly religious Protestants more likely to seek out discounted products compared to less religious Protestants (Sood and Nasu 1995).

Sustainability is another area that can be influenced by religion, since followers of Western religions are expected to be the least sustainable (because they believe that the world is likely to end soon when a savior returns) compared to those of Eastern religions and non-religious people (White 1967). Thus, consumers from western religions have much lower sustainable behavior compared to those from eastern religions (Djupe and Gwiasda 2010; Wolkomir et al. 1997). Health is another area that seems to be heavily connected with religion, since faith and religion have a positive effect on all serious diseases, from cancer to cardiovascular illnesses and can even prevent or alleviate mental illnesses, from depression to dementia and schizophrenia (Koenig et al. 2012).

Some theories that explain the influence of religion on consumer behavior are (1) attribution theory, that posits that the source of consumer actions can be internal or external to them (Kelley and Michela 1980), (2) self-determination theory, that is related to individuals’ motivations, which can also be external or internal (Deci and Ryan 2012). In (3) social learning theory, consumers learn attitudes and behaviors by observing those around them (Bandura 1971), making religious consumers that are close to their communities likely to behave similar to other members in their religious group. The theory of social relations (4) postulates that religious consumers may have more favorable impressions of companies or people in their (religiously affiliated) group and more unfavorable impressions of companies or people outside their group (Kenny and Voie 1984; Kenny 1994).

But still the relationship between religion and consumer behavior is one with many unknowns. For example Hood, Hill and Spilka (2009, p. 503) assert that „within the psychology of religion, the cry for a good theory remains at the level of cacophony“ Mathras et al. (2016, p. 2) also admit that „studies of the effects of religion on consumer psychology and behavior are scattered and have yet to be systematized, and much more remains to be discovered and explained“. Moreover, Agarwala et al. (2019, p. 14) state that „the knowledge on religion and its dimensions is at a preliminary stage, showing the need for more systematic research attention in the future“.

Taking a stand on the need for more quality research analyzing the complex relationships between religion and consumer behavior, this paper has the goal of researching certain aspects regarding religion, religiosity, and the purchase behavior of a long term good, mainly an air purifier, all in the post-pandemic context of the Coronavirus crisis. To achieve this goal, the following research objective emerged:

• Identify different aspects of consumer behavior related to air purifiers;

• Discover certain links between religion and purchase behavior of air purifiers;

• Identify aspect of consumer behavior of respondents from different religious groups;

• Identify respondents’ feelings related to air purifiers;

• Identify and analyze different themes that emerged from the current research.

Methodology

The participants were people over 22 years of age, men and women, permanent residents of Romania, with different religious choices. The selection criteria were for them to be family decision-makers and to have a stable income, thus being able to purchase an air purifier. Regarding religious affiliation, respondents belonging to three religious options were sought, as follows: (1) members of neo-protestant denominations, belonging to a religious minority in Romania, (2) members of the Orthodox Christian faith, being a religious majority and (3) atheists/agnostics, also a minority.

After screening more than 60 potential interview participants, 23 were selected based on the criteria outlined above. The participants had the following demographics: (a) 13 males (57%) and 10 females (43%); (b) 9 unmarried (39%), 5 married without children (22%), 5 married with children (22%) and 4 (17%) living with a partner; (c) 16 (70%) religiously affiliated, 7 (30%) not affiliated; (d) 4 (17%) Christian Orthodox, 11 (48%) Protestant, 8 (35%) atheist/agnostic; (e) 14 (61%) had a profound religious experience, 9 (39%) did not; (f) 8 (35%) had an extremely low religiosity level, 0 (0%) a low religiosity level, 6 (26%) a medium religiosity level, 6 (26%) a high religiosity level and 3 (13%) an extremely high religiosity level.

The data was collected through 45 open-ended questions segmented into several topics. The first one was the coronavirus pandemic, an issue of extreme importance in the lives of the participants. The second one focused on the purchase decision process for an air purifier, products that become extremely popular during the coronavirus pandemic, with people becoming very concerned about their personal health and the air they breathe (Sirtori-Cortina 2021). Topic three discussed religion from different points of view, from affiliation to religiosity, conversion, community and many more.

The procedure used to collect the qualitative information was the mobile instant messaging interview (MIMI), a hybrid between an open-ended questionnaire and the diary method, in which the respondent keeps a diary to record certain feelings and behaviors. The MIMI data collection method was used successfully by many authors (Kaufmann and Peil 2020; Pearce, Thøgersen-Ntoumani and Duda 2019; Maeng et al. 2016; García, Welford and Smith 2016), providing rich qualitative data, making it an innovative and powerful research tool. The resulting data was then analyzed qualitatively using Nvivo 12, manually coding each line of text, thus achieving a complex thematic framework.

When researching the relationship between religion and consumer behavior, one important aspect that arises is determining what product or service to analyze. This research has used an air purifier as a basis, due to several reasons, as follows:

• Prominent researchers also used ’’brown goods’’, which are durable electronics, such as television sets or stereo systems (Bailey and Sood 1993; Essoo and Dibb 2004) to analyze the relationship between religion and consumer behavior;

• The product used should be ’’free of religion’’ in order to identify if religion does influence aspects of consumer behavior that go beyond religious products and services;

• Analyzing a product or service that has religious connotations can be highly dependent on a certain religious denomination (most of them are), thus the results might be biased or may pertain to only that particular religious group;

• Air purifier products are closely tied to health prevention, and the scientific literature shows a very powerful indirect connection between religion and health (Koenig et al. 2012);

Marketing and consumer behavior has changed dramatically during the Covid 19 pandemic (Štrach 2020b, 2020a), making air purifiers very sought after products by consumers (Sirtori-Cortina 2021).

Results

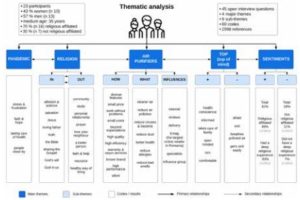

After coding and analyzing the data, the main themes of the interviews emerged as well as several sub-themes. Thus, five major themes were identified, as follows: (1) Pandemic; (2) Religion with sub-themes (2.1.) Inputs and (2.2.) Outputs; (3) Air purifiers, with sub-themes (3.1.) How they should be, (3.2.) What they should do (3.3) Influences; (4) Top of mind – in which participants were asked to write down the first words they associate with a person who uses air purifiers. This theme was divided into Positive (4.1.) and Negative (4.2.) traits. The last theme was the sentiment analysis for air purifiers (5) which was also divided into Positive (5.1.) and Negative (5.2.). All the themes were organized using the thematic framework in figure 1.

The pandemic theme used certain codes to analyze the data, and these were stress and frustration, faith and hope, taking care of health and people close by. Thus, almost all participants experienced negative feelings related to the pandemic, ranging from panic to outrage. These findings are in line with those of other researchers who examined aspects of the pandemic, finding extremely high levels of stress, similar to post-traumatic shock (Rossi et al. 2020; Rodríguez-Rey, Garrido-Hernansaiz and Collado 2020; Salari et al. 2020). Almost all the participants had an increase urgency to take care of their health, much more than the recommended measures. Also, the relationship between loved ones was important, since the lockdown has physically separated people, putting a toll on relationships. The religious individuals relied heavily on their faith, using prayer and other religious support mechanisms, bringing them hope in those stressful times. This is in line with the scientific literature which also found that during crises, religious people turn to their faith for help (Bentzen 2020; Jafari 2011; Koenig et al. 2012). Some extracts that exemplify this are:

„…I reflected on my life …what I had to change. There was a lot of prayer together, even though we were at a distance. I re-evaluated my values…and realized what a resource my faith is for me.“ Ariana (Orthodox Christian)

„Yet the hope that God is watching over us, despite the reality that is, gave me strength to move forward.“ Joanna (Evangelical Christian)

When discussing the religious theme, one of the aspects observed was the reluctance of some respondents and the extreme openness of others. Thus, the non-religious participants seemed disturbed and annoyed by questions about religion. This is in line with the view of other researchers (Mathras et al. 2016) who found religion to be a taboo and difficult topic to analyze. On the other hand, religious participants were extremely open to discussions, regardless of the affiliation. They seemed genuinely proud of their affiliation and characterized their relationship with the divine using terms such as „…it gives you a direction in life“ (Andreea C.), „… uninterrupted and personal relationship, based on the permanent presence of God within me“ (Claudiu), „…my identity in Christ“ (Andreea V.), „…God is within me“ (Ariana).

Figure 1: Thematic framework

Source: Author

Two subthemes of religion were identified, namely, inputs and outputs. The inputs subtheme attempted to identify aspects that could be considered determinants of religion and religiosity. The codes identified with religious inputs were atheism & science, salvation, Jesus, loving father, truth, the Bible, sharing the Gospel, God’s will, and God in us. Outputs are characterized by behavioral changes of the participants because of their religion with the following codes being observed: community, study, personal relationship, prayer, love your neighbor, a better person, faith & help, resource, healthy way of living. The results entail that the religious person is one of prayer, community and study, having a deep personal relationship with God. This relationship in turn is having a positive transformational effect of his live, with some extracts mentioning the following:

„God changed my life through His Word.“ (Marinela, Evangelical Christian)

„(my religion)… you could say that it changed my life.“ (Cristina, Evangelical Christian)

The air purifier theme was divided into three sub-themes, namely: how they should be, what they should do and influences. Regarding how they should be, the following codes emerged: diverse features, small price, work without problems, small costs, beyond expectations, high quality, high efficiency, warranty & return services, known brand, high performance and silent. Relating to what they should do, the following codes were used: cleaner air, reduce air pollution, reduce viruses & bacteria, reduce dust, better health, alleviate allergies and alleviate bad odors. The final subtheme was that of influences regarding the purchase decision process, and for this the codes created were the internet, reviews, delivery, Emag (the largest online retailer in Romania), specialists and influence groups.

The analysis between the religious and non-religious participants regarding the attributes sought after in an air purifier indicated a greater bias towards low prices and costs among religious people. These findings are in line with the ones of other researchers, attributing frugality and economic behavior to religious consumers, making them reluctant to acquire economic goods and when they do obtain them, they use them as economically as possible, maximizing the money spent (Sood and Nasu 1995; Essoo and Dibb 2004; Mokhlis 2006, 2009; Belk 1983).

The top-of-mind theme (TOP) was created after asking participants to write down the first three to five words they associate with a person using an air purifier. According to our analysis, a person who uses an air purifier has both positive and negative traits. With regards to the positives, he/she is health conscience, informed, takes care of family, is open minded, rich, and comfortable. When it comes to the negative aspects, he/she is afraid, sick or gets sick easily and breathes polluted air. Nonetheless, the code frequency for the positives greatly outnumbered that of the negatives, as it can be seem from the sentiment analysis.

Sentiment analysis was also performed, manually coding positives and negatives sentiments about air purifiers in Nvivo. For example, the text „I find them useful for small, unventilated spaces (Narcis)“ was coded as positive, whereas extracts such as „I don’t think I will use this type of products any time soon (Adrian)“ were coded as negative. Thus, it was possible to quantify how many references (number of times the codes were used) were positive and how many negative, thus extracting the respondents’ feelings. Most of the codes regarding sentiments were positives (82%), much more so for the religious affiliated (89%) and for participants who had a deep religious experience at some point in their lives (93%).

Discussion

The qualitative analysis of the 23 interviews using thematic and sentiment analysis provided interesting insights into aspects regarding religion, consumer behavior and the buying behavior of air purifiers. Overall, air purification products seem to be well received by consumers, with 82% of participants having positive feelings about them. But nevertheless, the expectations that consumers have about what these products should do are extremely high, and to satisfy them, air purifiers need to be well above expectations. The internet, large online stores and reviews have been identified as extremely important, both in the information gathering step but also when it comes to acquisition. The opinion of others, whether digital in the form of reviews or traditional, through reference group members is also a key factor in the decision process for acquiring an air purifier.

According to the stages of the purchasing decision process identified by researchers such as Hawkins and Mothersbaugh (2010) or Cătoiu and Teodorescu (2007), the following aspects were discovered about the purchase of an air purifier:

(1) Unmet need occurs as a result of polluted air, indoor dust, allergies, wanting to eliminate unpleasant odors, the desire to be healthy and to protect ones family;

(2) Researching information takes from a few hours to a few weeks, starts with internet searches and relies heavily on the opinions of others in the form of reviews, reference groups and specialists;

(3) Evaluating the alternatives are done through reviews, price, future costs, the brand, the quality, and the variety of features. Also, the product should function properly and exceed expectations. This is mostly done using the internet and large online retailers;

(4) Result of the evaluation shows that once chosen, the product will be ordered online and aspects such as free delivery and return policies are very important;

(5) Post-purchase evaluation discovered that the product will be returned if it does not live up to expectations or if it does not work properly. If it exceeds expectations, the consumer will tell others about it through word of mouth and online reviews.

Regarding religion, the faithful person is one of learning, study and community, aspects that can have an influence on his buying behavior. The religious person tends to deeply analyze topics and products of interest, with many religious participants stating that they would take even a couple of weeks to analyze the purchase of an air purifier. Another key aspect of the religious person is the importance of community, most of them having close relationships with other members of their religious group, this being also in line with other authors (Bandura 1971; Mathras et al. 2016).

Another aspect identified with consistent scientific support (Agarwala, Mishra and Singh 2019) is the frugality and economic behavior of the religious individual, who places high value on aspects such as price, subsequent costs, consumables and free delivery. Thus, the religious person is a demanding consumer, extremely careful with money, analyzing in detail and over a long period of time all key aspects of a purchase. Another characteristic of the religious man is a diminished fear of illness and viruses, which is one of the key selling points of air purifiers. Although they are interested in protecting their health, they do not seem to do so out of fear, with almost all religious respondents stating that they rely on God for protection. Thus, there seems to be certain distinct consumer behavior patterns of the religious individual, or homo religious (van der Leeuw 1933).

This study has brought forth a series of contributions, both to academia and to the commercial aspect of marketing. First, it added more knowledge to the under researched area of religion and consumer behavior, a topic strongly needing more studies. Secondly, it has done so using a qualitative approach, uncovering subtle nuances of the consumer behavior of the religious individual. Thirdly, the results provided meaningful and actionable tactics for companies producing and selling air purifiers, a segment extremely popular after the Coronavirus pandemic.

Far from perfect, the current research is limited, having a very specific product for analysis that might influence in part the results. Also, the number of interviews was limited to only 23 and due to the qualitative type of data, no statistical analysis could be performed. Future works can analyze other aspects regarding the relationship between religion and consumer behavior, also using other types of products and services, thus largening the knowledge that still is in its infancy. Also using in-depth qualitative data can give subtle insights into the consumer behavior of the religious man, aspect that might not be perceived by a purely quantitative design. As one religious song goes, the fields are ready for harvest, but the workers are so few, as this is also the case with regards to the research between religion and consumer behavior.

Literatúra/List of References

- Agarwala, R., Prashant, M. and Ramendra, S., 2019. Religiosity and consumer behavior: A summarizing review. In: Journal of Management, Spirituality & Religion. 2019, 16(1), 32-54. ISSN 1476-6086.

- Bandura, A., 1971. Social learning theory. New York, NY: General Learning Press, 1971.

- Belk, R. W., 1983. Worldly possessions: Issues and criticisms. In: Advances in Consumer Research. 1983, 10, 514-19. ISSN 0098-9258.

- Bentzen, J., 2020. In crisis, we pray: Religiosity and the COVID-19 pandemic. In: CEPR Discussion Paper No. DP14824. [online]. [cit. 2022-8-20]. Available at: <https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=3615587>

- Deci, E. and Ryan, R. M., 2012. Self-determination theory. In: Handbook of theories of social psychology, ed. Van Lange, P. A. M., Kruglanski, A. W. and Higgins, E. T., Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2012, 416-37. ISBN 9780857029607.

- Djupe, P. A. and Gwiasda, G. W., 2010. Evangelizing the environment: Decision process effects in political persuasion. In: Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 2010, 49(1), 73-86. ISSN 1468-5906.

- Essoo, N. and Dibb, S., 2004. Religious influences on shopping behaviour: An exploratory study. In: Journal of Marketing Management. 2004, 20(7-8), 683-712. ISSN 1472-1376.

- García, B., Welford, J. and Smith, B., 2016. Using a smartphone app in qualitative research: The good, the bad and the ugly. In: Qualitative Research: QR. 2016, 16(5), 508-25. ISSN 1468-7941.

- Hawkins, D. I. and Mothersbaugh, D. L., 2010. Consumer behavior: Building marketing strategy. McGraw-Hill: Irwin, 2010. ISBN 9780073381107.

- Hirschman, E. C., 1981. American-Jewish ethnicity: Its relationship to some selected aspects of consumer behavior. In: Journal of Marketing, 1981, 45, 102-10. ISSN 0309-0566.

- Hirschman, E. C., 1983. Religious affiliation and consumption processes: An initial paradigm. In: Research in marketing, ed. Sheth, J. N., 1983, Greenwich, CT: JAI Press, 131-70.

- Hood, R. W., Hill, P. C. and Spilka, B., 2009. The psychology of religion: An empirical approach. New York, NY: Guilford Press, 2009. ISBN 978-1-60623-303-0.

- Jafari, A., 2011. Relationship between religious orientation (internal-external) with methods of overcoming stress in students of Islamic Azad University of Abhar. In: Psychology Research and Behavior Management. 2011, 1(4), 239-43. ISSN 1179-1578.

- Kahle, L. R., 1996. Social values and consumer behaviour: Research from the list of values. In: The psychology of values: The Ontario symposium, 1996, ed. Seligman, C. and Olson, J. P., Vol. 8. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum. ISBN 9781138989788

- Kahle, Lynn R. and Valette-Florence, P., 2012. Marketplace lifestyles in an age of social media: Theory and Methods. Routledge, 2012. ISBN 9780765625618.

- Kaufmann, K. and Peil, C., 2020. The mobile instant messaging interview (MIMI): Using WhatsApp to enhance self-reporting and explore media usage in situ. In: Mobile Media & Communication. 2020, 8(2), 229-46. ISSN 2050-1579.

- Kelley, H. H. and Michela, J. L., 1980. Attribution theory and research. In: Annual Review of Psychology. 1980, 31(1), 457-501. ISSN 00664308.

- Kenny, D. A., 1994. Interpersonal perception: A social relations analysis. New York, NY: Guilford Press, 1994. ISBN 9780898621143.

- Kenny, D. A. and Voie, L., 1984. The social relations model. In: Advances in Experimental Social Psychology. 1984, 18, 142-82. ISSN 0065-2601.

- Koenig, H., Koenig, H. G., King, D. and Carson, V. B., 2012. Handbook of religion and health. USA: Oxford University Press, 2012.

- Leeuw, G. van der, 1933. Phanomenologie Der Religion. Harper & Row, 1933.

- Lipka, M., 2015. Seven key changes in the global religious landscape. In: Pew Research Center 2. [online]. [cit. 2022-8-20]. Available at: <https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2015/04/02/7-key-changes-in-the-global-religious-landscape/>

- Maeng, W., Yoon, J., Ahn, H. and Lee, J., 2016. Can mobile instant messaging be a useful interviewing tool? A comparative analysis of phone use, instant messaging and mobile instant messaging. In: Proceedings of HCI Korea, 2016, 45-49. HCIK’16. Seoul, KOR: Hanbit Media, Inc.

- Mathras, D., Cohen, A. H., Mandel, N. and Mick, D. G., 2016. The effects of religion on consumer behavior: A conceptual framework and research agenda. In: Journal of Consumer Psychology. 2016, April. ISSN 1057-7408. [online]. [cit. 2022-8-20]. Available at: <https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2787454>

- Minton, E. A. and Kahle, L. R., 2013. Belief systems, religion and behavioral economics. Business Expert Press. ISBN 978-1606497043.

- Minton, E. A. and Kahle, L. R., 2016. Religion and consumer behaviour. In: Routledge International Handbook of Consumer Psychology, ed. Jansson-Boyd, C. V. and Zawisza, M. J., 2016, 292-311. ISBN 9781315727448.

- Mittelstaedt, J., 2002. A framework for understanding the relationships between religions and markets. In: Journal of Macromarketing. 2002, 22(1), 6-18. ISSN 0276-1467.

- Mokhlis, S., 2006. The effect of religiosity on shopping orientation: An exploratory study in Malaysia. In: Journal of American Academy of Business. 2006, 9(1), 64-74. ISSN 1540-7780.

- Mokhlis, S., 2009. Religious differences in some selected aspects of consumer behaviour: A Malaysian study. In: The Journal of International Management Studies. 2009, 4(1), 67-76. ISSN 2378-9557.

- Oxtoby, W. G. and Hussain, A., 2010. World religions: Western traditions. Oxford University Press, 2010. ISBN 9780190877071.

- Pearce, G., Thøgersen-Ntoumani, C. and Duda, J. L., 2019. Synchronous text-based instant messaging: Online interviewing tool. In: Handbook of Research Methods in Health Social Sciences, ed. Liamputtong, P., Singapore: Springer Singapore, 2019, 1369-83. ISBN 9789811052507.

- Pew Research Center. 2017. The changing global religious landscape. Pew Research Center. [online]. [cit. 2022-8-20]. Available at: <https://assets.pewresearch.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/11/2017/04/07092755/FULL-REPORT-WITH-APPENDIXES-A-AND-B-APRIL-3.pdf>

- Rinallo, D., Scott, L., and Maclaran, P., 2012. Consumption and spirituality. New York, NY: Routledge, 2012. ISBN 978-0-203-10623-5.

- Rodríguez-Rey, R., Garrido-Hernansaiz, H. and Collado, S., 2020. Psychological impact and associated factors during the initial stage of the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic among the general population in Spain. In: Frontiers in Psychology. 2020, 11 (June), 1540. ISSN 1664-1078.

- Rossi, R., Socci, V., Talevi, D., Mensi, S., Niolu, C., Pacitti, F., Di Marco, A., Rossi, A., Siracusano, A. and Di Lorenzo, G., 2020. COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown measures impact on mental health among the general population in Italy. In: Frontiers in Psychiatry. 2020, 11(August), 790. ISSN 16640640.

- Salari, N., Hosseinian-Far, A., Jalali, R., Vaisi-Raygani, A., Rasoulpoor, S., Mohammadi, M., Rasoulpoor, S. and Khaledi-Paveh, B., 2020. Prevalence of stress, anxiety, depression among the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. In: Globalization and Health. 2020, 16(1), 57. ISSN 1744-8603.

- Shachar, R., Erdem, T., Cutright, K. M. and Fitzsimons, G. J., 2011. Brands: the opiate of the nonreligious masses? In: Marketing Science. 2011, 30(1), 92-110. ISSN 0732-2399.

- Sirtori-Cortina, D., 2021. Covid-19 and wildfires spell big business for the air purifier industry. In: Bloomberg News, August 5, 2021. [online]. [cit. 2022-8-20]. Available at: <https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2021-08-05/covid-19-and-wildfires-are-driving-a-big-increase-in-u-s-air-purifier-sales>

- Sood, J. and Nasu, Y., 1995. Religiosity and nationality: An exploratory study of their effect on consumer behavior in Japan and the United States. In: Journal of Business Research. 1995, 34(1), 1-9. ISSN 0148-2963.

- Štrach, P., 2020a. Before, during, and after: Marketing amid coronavirus crisis. In: Marketing Science & Inspirations. 2020, 15(1), 49-50. ISSN 1338-7944. [online]. [cit. 2022-8-20]. Available at: <https://msijournal.com/before-during-and-after-marketing-amid-coronavirus-crisis/>

- Štrach, P., 2020b. How covid-19 is changing consumer behavior: Identifying new segments and segmentation criteria. In: Marketing Science & Inspirations. 2020, 15(4), 52-53. ISSN 1338-7944. [online]. [cit. 2022-8-20]. Available at: <https://msijournal.com/covid-19-consumer-behavior/>

- White, L., 1967. The historical roots of our environmental crisis. In: Science. 1967, 155(3767), 1203-7. ISSN 1339-3049.

- Wolkomir, M. J., Futreal, M., Woodrum, E. and Hoban, T., 1997. Denominational subcultures of environmentalism. In: Review of Religious Research. 1997, 38(4), 325-43. ISSN 2211-4866.

Kľúčové slová/Key words

religion, consumer behavior, thematic and sentiment analysis

náboženstvo, spotrebiteľské správanie, tematická a sentimentová analýza

JEL klasifikácia/JEL Classification

M31

Résumé

Tematická a sentimentová analýza vzťahu medzi náboženstvom a nákupným správaním

Keďže viac ako 70% sveta uznáva náboženstvo, existuje naliehavá potreba lepšie pochopiť vzťah medzi náboženstvom a správaním spotrebiteľov. Cieľom tejto štúdie je analyzovať nákupné správanie náboženských a nenáboženských spotrebiteľov pri kúpe produktu – čističa vzduchu. To sa dosiahlo prostredníctvom 23 kvalitatívnych rozhovorov pomocou metódy mobilných okamžitých správ (MIMI). Pomocou tematickej a sentimentovej analýzy boli identifikované dôležité témy ako pandémia, náboženstvo, ale aj pocity a vzorce nákupného správania čističa vzduchu. Okrem toho boli identifikované jemné nuansy týkajúce sa spotrebiteľského správania náboženského jedinca, ako je šetrnosť a sila náboženských komunít. Výstupy tohto príspevku môžu prispieť akademickej obci aj manažmentu organizácií. Ponúkajú sa výstupy analýzy vybraných aspektov vzťahu medzi náboženstvom a správaním spotrebiteľov pomocou využitia hĺbkových kvalitatívnych metód.

Recenzované/Reviewed

15. September 2022 / 28. September 2022